As a freed man, Equiano traveled and became increasingly engaged in the campaign against the Atlantic Slave Trade and slavery. He was known as the best known black abolitionist of his time. He belonged to the London-based black Civil Rights organization, Sons of Africa. He also worked with British abolitionists seeking to ameliorate the condition of poor black people in England and Canada by settling them in the new British West African colony of Sierra Leone. He was also the leader of the poor black community in London and a prominent figure in the political realm and oftentimes served as a voice for his people.

Personal Life & Writing

Married Susannah (Susan) Cullen on April 7, 1792. He had two daughters, Anna Maria (1793-1797) and Joanna (1795-1857). Susannah died February 1796, aged 34. Equiano died a year after that on March 31, 1797, aged 52. Soon after, the elder daughter, Anna Maria, died, aged four years old, leaving Joanna to inherit Equiano’s estate which was valued at 950 British pounds, worth approximately 100,000 British pounds today, or 160,000 American dollars.

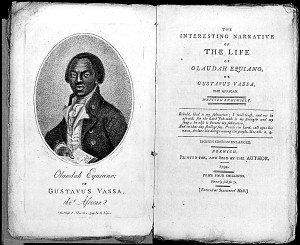

In 1788 he began writing The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African, published in 1789, as a weapon in the war against slavery. This story laid the foundation of a great American literary genre. His story was also an international bestseller and was reprinted seven times in its first five years of publication. His story was well known and admired throughout the English-speaking world.

In his story he recognized the horror of the institutions of slavery and the slave trade and he worked to abolish the evils he had personally experienced. Helped influence British lawmakers to abolish the slave trade through the Slave Trade Act of 1807. His story paints the earliest persuasive picture of an Eden-like Africa, a picture that influenced African Americans’ subsequent ideas about their ancestral homeland. He also described kidnappers, who with the permission of greedy chiefs took prisoners for the sole purpose of sale.

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa was one of the earliest known examples of published writing by an African writer to be widely read in England. It was also the first influential slave autobiography and fueled a growing anti-slavery movement in Great Britain. The book also increased Equiano’s personal revenue and allowed him to travel a lot, promoting the book.

He also wrote about how slave working inside the slaveholder’s homes in Virginia were treated cruelly with what was called the “iron muzzle” treatment. Equiano’s expose on The Zong, a slave ship that threw 133 slaves overboard was said to shake the British nation.

Conflict of Origin

Arguments that Equaino was born in South Carolina

Some believe that Equiano may have fabricated his African roots and his survival of the Middle Passage not only to sell more copies of his book but also to help advance the movement against the slave trade. Baptismal records and a naval muster roll appear to link Equiano to South Carolina. Records of Equaino’s first voyage were from Carolina, not Africa. Equiano never used the name “Equiano” before publishing his autobiography. All his friends and acquaintances knew him by the name “Gustavus Vassa”. He probably made up the name “Olaudah Equiano” as part of the careful construction of an African persona he carried out in 1789. Much of the early part of The Interesting Narrative, in which Equiano describes Africa and the middle passage, closely resembles similar accounts made by European or American authors.

Arguments that Equiano was born in Africa

This may have been a clerk’s careless record of origin. Many parts of Equiano’s account can be proven lends weight to his story of African birth. Although Equiano gets the dates wrong about the ships in which he was brought from America to England, he was a very young child at the time, and suffered a severe trauma, so it is reasonable to assume that his memory might sometimes be at fault. Although Equiano never used his birth name before 1789, this was not unusual. Few slaves or former slaves used their African names. Equiano knew that the most intensive search would be made by proslavery campaigners to discredit him. Therefore, he would not have attempted to invent a new identity and birthplace.