“The Secret Meeting that Changed Rap Music

and

Destroyed a Generation“

HIP HOP IS READ

The unsigned letter below was originally posted on the blog Hip Hop is Read, and was written by a self-proclaimed “decision-maker” working for an equally anonymous major record label.

The anonymous nature of the letter led many to dismiss it as a bogus piece of conspiracy theory; however, before you jump to the same conclusion, consider the fact that judges have been convicted and gone to jail for exactly the same thing that this letter claims happened.

“Splatter the brain matter of my enemies/With the same bullet trajectory that murdered John Kennedy.” —Canibus, “Boyz 2 Men” 50 years ago today, President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas, Texas. It spawned an entire industry of conspiracy theorists, obsessed with men on a grassy knoll, CIA plots, and bullet trajectories. Hip-hop has long had its own culture of conspiracy. Of course, hip-hop’s conspiracy fascination is rooted in very real distrust of the government within the Black community, based on years of exploitation and abuse. After all, what is the Tuskegee Experiment but a “conspiracy” that turned out to be 100 percent true? That’s not to compare people who think Pac is still alive with those rightly distrustful of government’s role in proliferating racism and oppression. It’s also not intended to excuse conspiracy-mongering. But it does help explain why this attitude is so prevalent in hip-hop.“

www.hiphopisread.com Posted by Ivan: @hiphopisread.com http://www.hiphopisread.com/2012/04/secret-meeting-that-changed-rap-music.html

“Hello, “After more than 20 years, I’ve finally decided to tell the world what I witnessed in 1991, which I believe was one of the biggest turning points in popular music and ultimately American society. I have struggled for a long time weighing the pros and cons of making this story public as I was reluctant to implicate the individuals who were present that day. So I’ve simply decided to leave out names and all the details that may risk my personal well-being and that of those who were, like me, dragged into something they weren’t ready for. Between the late ’80s and early ’90s, I was what you may call a “decision maker” with one of the more established companies in the music industry. I came from Europe in the early ’80s and quickly established myself in the business. The industry was different back then. Since technology and media weren’t accessible to people like they are today, the industry had more control over the public and had the means to influence them any way it wanted. This may explain why in early 1991, I was invited to attend a closed-door meeting with a small group of music business insiders to discuss rap music’s new direction. Little did I know that we would be asked to participate in one of the most unethical and destructive business practices I’ve ever seen.

The meeting was held at a private residence on the outskirts of Los Angeles. I remember about 25 to 30 people being there, most of them familiar faces. Speaking to those I knew, we joked about the theme of the meeting as many of us did not care for rap music and failed to see the purpose of being invited to a private gathering to discuss its future. Among the attendees was a small group of unfamiliar faces who stayed to themselves and made no attempt to socialize beyond their circle. Based on their behavior and formal appearances, they didn’t seem to be in our industry. Our casual chatter was interrupted when we were asked to sign a confidentiality agreement preventing us from publicly discussing the information presented during the meeting. Needless to say, this intrigued and in some cases disturbed many of us.

The agreement was only a page long but very clear on the matter and consequences which stated that violating the terms would result in job termination. We asked several people what this meeting was about and the reason for such secrecy but couldn’t find anyone who had answers for us. A few people refused to sign and walked out. No-one stopped them. I was tempted to follow but curiosity got the best of me. A man who was part of the “unfamiliar” group collected the agreements from us. Quickly after the meeting began, one of my industry colleagues (who shall remain nameless like everyone else) thanked us for attending. He then gave the floor to a man who only introduced himself by his first name and gave no further details about his personal background. I think he was the owner of the residence but it was never confirmed. He briefly praised all of us for the success we had achieved in our industry and congratulated us for being selected as part of this small group of “decision-makers”. At this point, I begin to feel slightly uncomfortable at the strangeness of this gathering.

The subject quickly changed as the speaker went on to tell us that the respective companies we represented had invested in a very profitable industry which could become even more rewarding with our active involvement. He explained that the companies we work for had invested millions into the building of privately owned prisons and that our positions of influence in the music industry would actually impact the profitability of these investments. I remember many of us in the group immediately looking at each other in confusion. At the time, I didn’t know what a private prison was but I wasn’t the only one. Sure enough, someone asked what these prisons were and what any of this had to do with us. We were told that these prisons were built by privately-owned companies that received funding from the government based on the number of inmates. The more inmates, the more money the government would pay these prisons. It was also made clear to us that since these prisons are privately owned, as they become publicly traded, we’d be able to buy shares.

Most of us were taken back by this. Again, a couple of people asked what this had to do with us. At this point, my industry colleague who had first opened the meeting took the floor again and answered our questions. He told us that since our employers had become silent investors in this prison business, it was now in their interest to make sure that these prisons remained filled. Our job would be to help make this happen by marketing music that promotes criminal behavior, rap being the music of choice. He assured us that this would be a great situation for us because rap music was becoming an increasingly profitable market for our companies, and as employees, we’d also be able to buy personal stocks in these prisons. Immediately, silence came over the room. You could have heard a pin drop.

I remember looking around to make sure I wasn’t dreaming and saw half of the people with dropped jaws. My daze was interrupted when someone shouted, “Is this a f****** joke?” At this point things became chaotic. Two of the men who were part of the “unfamiliar” group grabbed the man who shouted out and attempted to remove him from the house. A few of us, myself included, tried to intervene. One of them pulled out a gun and we all backed off. They separated us from the crowd and all four of us were escorted outside. My industry colleague who had opened the meeting earlier hurried out to meet us and reminded us that we had signed an agreement and would suffer the consequences of speaking about this publicly or even with those who attended the meeting. I asked him why he was involved with something this corrupt and he replied that it was bigger than the music business and nothing we’d want to challenge without risking consequences.

We all protested and as he walked back into the house I remember word for word the last thing he said, “It’s out of my hands now. Remember you signed an agreement.” He then closed the door behind him. The men rushed us to our cars and actually watched until we drove off. A million things were going through my mind as I drove away and I eventually decided to pull over and park on a side street in order to collect my thoughts. I replayed everything in my mind repeatedly and it all seemed very surreal to me. I was angry with myself for not having taken a more active role in questioning what had been presented to us. I’d like to believe the shock of it all is what suspended my better nature. After what seemed like an eternity, I was able to calm myself enough to make it home. I didn’t talk or call anyone that night. The next day back at the office, I was visibly out of it but blamed it on being under the weather. No one else in my department had been invited to the meeting and I felt a sense of guilt for not being able to share what I had witnessed. I thought about contacting the 3 others who wear kicked out of the house but I didn’t remember their names and thought that tracking them down would probably bring unwanted attention.

I considered speaking out publicly at the risk of losing my job but I realized I’d probably be jeopardizing more than my job and I wasn’t willing to risk anything happening to my family. I thought about those men with guns and wondered who they were? I had been told that this was bigger than the music business and all I could do was let my imagination run free. There were no answers and no one to talk to. I tried to do a little bit of research on private prisons but didn’t uncover anything about the music business’ involvement. However, the information I did find confirmed how dangerous this prison business really was. Days turned into weeks and weeks into months. Eventually, it was as if the meeting had never taken place. It all seemed surreal. I became more reclusive and stopped going to any industry events unless professionally obligated to do so. On two occasions, I found myself attending the same function as my former colleague. Both times, our eyes met but nothing more was exchanged. As the months passed, rap music had definitely changed direction. I was never a fan of it but even I could tell the difference.

Rap acts that talked about politics or harmless fun were quickly fading away as gangster rap started dominating the airwaves. Only a few months had passed since the meeting but I suspect that the ideas presented that day had been successfully implemented. It was as if the order has been given to all major label executives. The music was climbing the charts and most companies when more than happy to capitalize on it. Each one was churning out their very own gangster rap acts on an assembly line. Everyone bought into it, consumers included. Violence and drug use became a central theme in most rap music. I spoke to a few of my peers in the industry to get their opinions on the new trend but was told repeatedly that it was all about supply and demand. Sadly many of them even expressed that the music reinforced their prejudice of minorities.

I officially quit the music business in 1993 but my heart had already left months before. I broke ties with the majority of my peers and removed myself from this thing I had once loved. I took some time off, returned to Europe for a few years, settled out of state, and lived a “quiet” life away from the world of entertainment. As the years passed, I managed to keep my secret, fearful of sharing it with the wrong person but also a little ashamed of not having had the balls to blow the whistle. But as rap got worse, my guilt grew. Fortunately, in the late ’90s, having the internet as a resource that wasn’t at my disposal in the early days made it easier for me to investigate what is now labeled the prison industrial complex.

Now that I have a greater understanding of how private prisons operate, things make much more sense than they ever have. I see how the criminalization of rap music played a big part in promoting racial stereotypes and misguided so many impressionable young minds into adopting these glorified criminal behaviors which often lead to incarceration. Twenty years of guilt is a heavy load to carry but the least I can do now is to share my story, hoping that fans of rap music realize how they’ve been used for the past 2 decades. Although I plan on remaining anonymous for obvious reasons, my goal now is to get this information out to as many people as possible. Please help me spread the word. Hopefully, others who attended the meeting back in 1991 will be inspired by this and tell their own stories. Most importantly, if only one life has been touched by my story, I pray it makes the weight of my guilt a little more tolerable.” Thank you

*****

“Rap is something you do. Hip Hop is what you are”

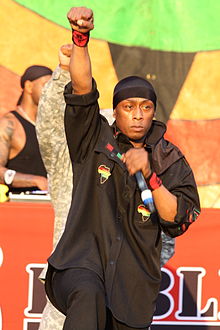

Richard Griffin (born August 1, 1960), better known by his stage name Professor Griff, is an American rapper, spoken word artist, lecturer, and martial artist, currently residing in Atlanta. He was a member of the hip hop group Public Enemy, serving as the group’s Minister of Information before departing due to a controversy regarding homophobic and anti-semitic statements made during his interviews. Griffin was born in Roosevelt, Long Island, New York. Before becoming famous and after serving in the U.S. Army he started a security company called Utility Force to do security at parties. He is most known for his S1W security team dressed in military uniforms who toured with Public Enemy, providing security and doing choreographed military step drills on stage. Today he does lectures on politics, society and the music industry has an internet radio show on World Star Hit Radio, and teaches classes in the Kybalion and The 7 Hermetic Principles for Self-Mastery.

LOS ANGELES, CA – APRIL 16: Professor Griff in the green room before An Evening With Public Enemy at The GRAMMY Museum on April 16, 2013, in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Mark Sullivan/WireImage)

Before the release of It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Professor Griff, in his role as Minister of Information, gave interviews to UK magazines on behalf of Public Enemy, during which he made homophobic and anti-Semitic remarks. In a 1988 issue of Melody Maker, he stated “There’s no place for gays. When God destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah, it was for that sort of behavior” and “If the Palestinians took up arms, went into Israel and killed all the Jews, it’d be alright” However, there was little controversy until May 22, 1989, when Griffin was interviewed by the Washington Times. At the time, Public Enemy enjoyed unprecedented mainstream attention with the single “Fight the Power” from the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing.

During the interview with David Mills, Griffin made numerous statements such as “Jews are responsible for the majority of the wickedness in the world”. When the interview was published, a media firestorm emerged, and the band found itself under intense scrutiny.

In a series of press conferences, Griffin was either fired, quit, or never left. Def Jam co-founder Rick Rubin had already left the label by then; taking his place alongside Russell Simmons was Lyor Cohen, the son of Israeli immigrants who had run Rush Artist Management since 1985. Before the dust settled, Cohen claims to have arranged for a Holocaust Museum to give the band a private tour.

In an attempt to defuse the situation, Ridenhour first expressed an apology on his behalf and fired Griffin soon thereafter. Griffin later rejoined the group, provoking more protests, causing Ridenhour to briefly disband the group. When Public Enemy reformed, due to increasing attention from the press and pressure from Def Jam hierarchy, Griffin was no longer with the band.

Griffin later publicly expressed remorse for his statements after a meeting with the National Holocaust Awareness Student Organization in 1990.

In his 2009 book, titled Analytixz, Griff once again admitted the faults in his alleged 1989 statement: “To say the Jews are responsible for the majority of wickedness that went on around the globe, I would have to know about the majority of wickedness that went on around the globe, which is impossible…I’m not the best knower—God is. Then, not only knowing that, I would have to know who is at the crux of all of the problems in the world and then blame Jewish people, which is not correct.” Griff also said that not only were his words taken out of context but that the recording was never released to the public for an unbiased listen. In a YouTube interview on August 2, 2018 Professor Griff recalled one of his many long conversations with record executive Lyor Cohen he said he used to have respectful debates about history “I told him about the history of him and his people about the Ashkenazi, the Ashke-Nazis and when I laid it on him he couldn’t handle it and I’m like alright, which is common knowledge today everybody talking about it, you understand what I’m saying people are making books about it. (8:23)

Griffin embraces a radical form of Afrocentrism. “Muslim, Christian, Jew, Here’s a little somethin’ I thought you knew/There is only one God and God is one, the rich praises none.”

After his departure from Public Enemy, Griffin formed his own group, the Last Asiatic Disciples. Griffin’s albums were of an Islamic and Afrocentric style, combined with increasingly spoken word lyrics.

He was a member of the Nation of Islam, which his lyrics and record titles as a solo artist referenced. Another general theme in his lyrics is New World Order conspiracy. On August 27, 2017, Professor Griff married longtime friend, Solé (previously married to R&B Singer Ginuwine). The couple met 27 years earlier and resumed their relationship after Solé and Ginuwine divorced.

*****

Political Rappers

List of political hip-hop artists. In hip-hop music, political hip-hop, or political rap, is a form developed in the 1980s, inspired by 1970s political preachers such as The Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron. Public Enemy was the first political hip hop group to gain commercial success.

*****

Private prisons: How US corporations make money out of locking you up

Published on Aug 10, 2018

NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED