THE

ORANGEBURG

MASSACRE

by DALE RICARDO SHIELDS

“One of the deadliest yet least acknowledged acts of state violence of the Civil Rights Movement.“

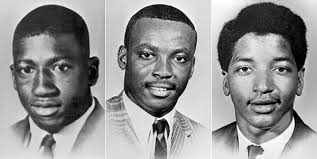

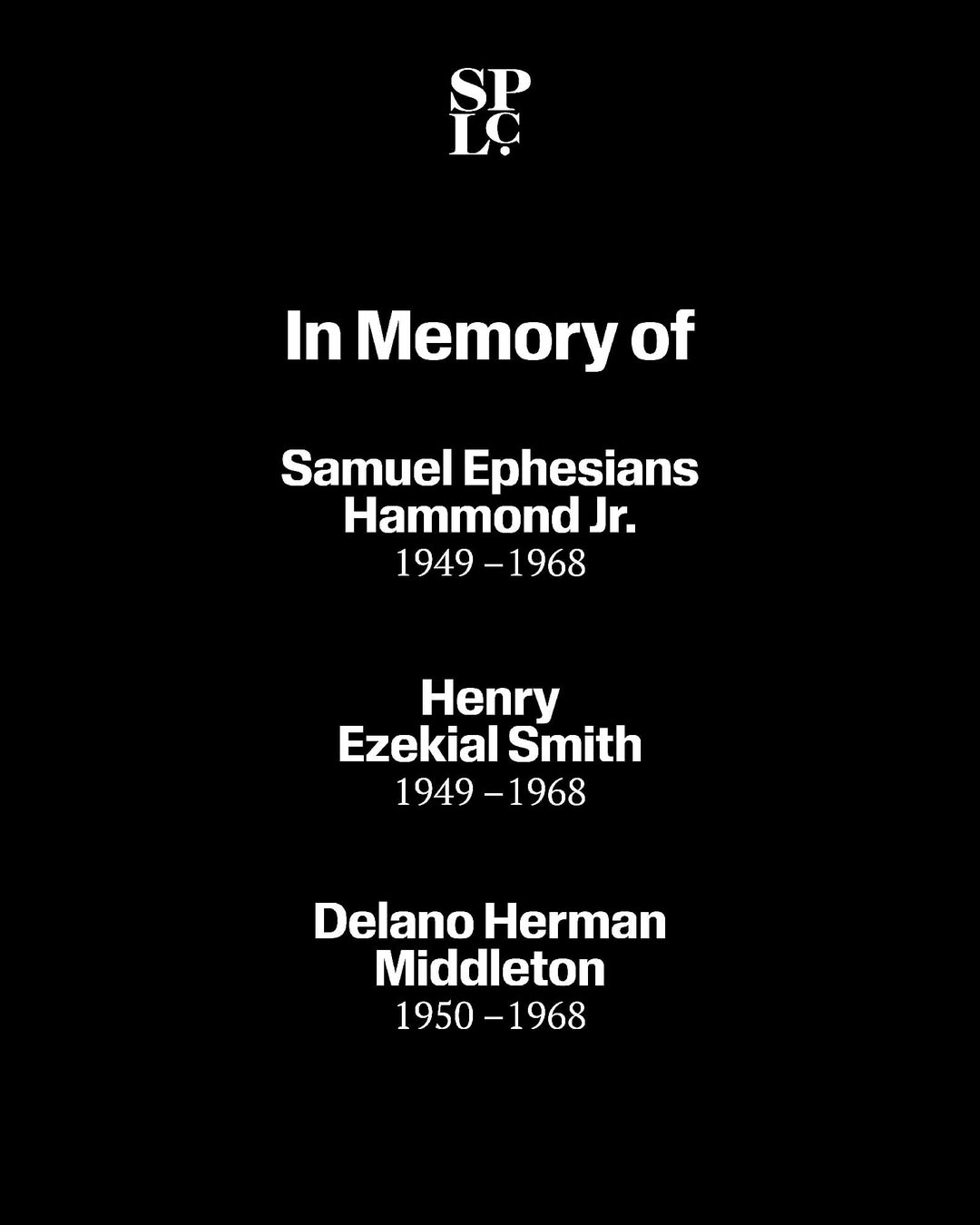

In 1968, police opened fire on students at South Carolina State University during a peaceful demonstration, killing Samuel Ephesians Hammond Jr., Delano Herman Middleton and Henry Ezekial Smith.

The protest was part of ongoing efforts by students from South Carolina State University and nearby Claflin University to desegregate a whites-only bowling alley in Orangeburg.

Nine officers fired into the crowd. All were acquitted. The state of South Carolina has never fully investigated what happened that night.

The Orangeburg Massacre remains one of the deadliest yet least acknowledged acts of state violence of the Civil Rights Movement.

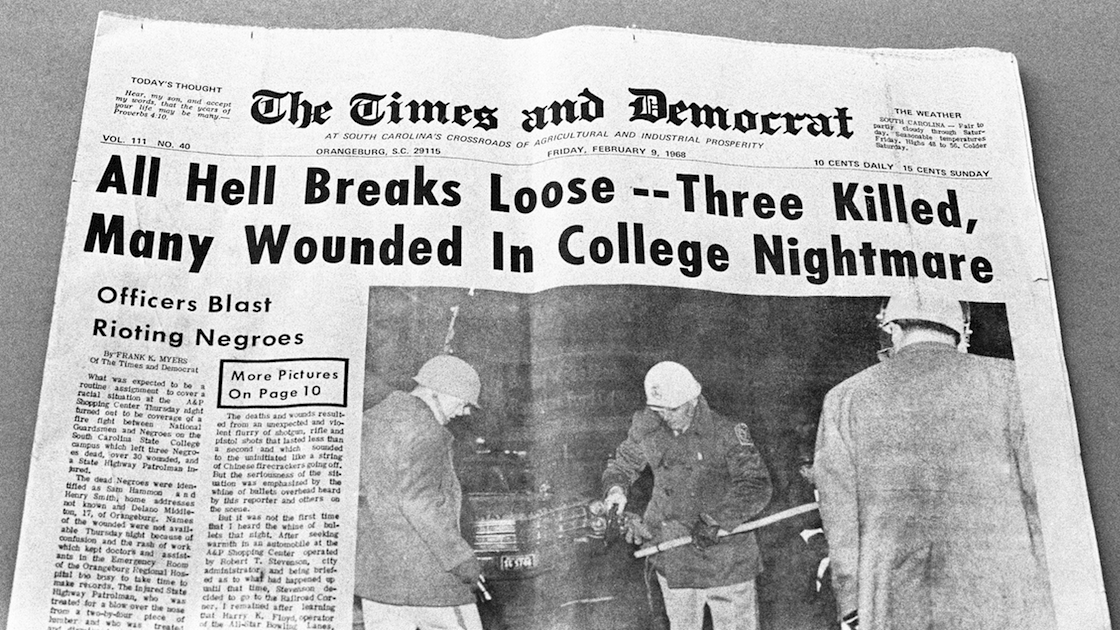

The Orangeburg Massacre refers to the shooting of unarmed Black student protesters by South Carolina Highway Patrol officers on February 8, 1968, on the campus of South Carolina State University.

The tragedy was the culmination of three days of protests against the racial segregation of the All Star Bowling Lane, the only bowling alley in Orangeburg, which continued to refuse service to Black patrons despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Key Facts

-

Casualties: Three young men were killed: Samuel Hammond Jr. (18), Henry Smith (18), and Delano Middleton (17). Another 28 protesters were wounded, many shot in the back while fleeing.

-

Historical Significance: It was the first instance in U.S. history of police killing student protesters on a college campus, predating the Kent State shootings by two years.

-

The Incident: Tensions peaked on the night of February 8 when students gathered around a bonfire on campus. As law enforcement moved to extinguish the fire, a police officer was struck by a thrown object. Shortly after, officers opened fire on the crowd for approximately eight seconds using shotguns and carbines.

-

Legal Aftermath: Nine highway patrolmen were later tried in federal court for using excessive force but were all acquitted. Conversely, activist Cleveland Sellers, who was wounded in the shooting, was the only person convicted and jailed on charges of inciting a riot; he was not pardoned until 1993.

Legacy and Commemoration

Today, South Carolina State University honors the victims through the Smith-Hammond-Middleton Legacy Plaza and an annual memorial service. In 2001, Governor Jim Hodges issued the first formal state apology for the massacre. On February 8, 2026, the university marked the 58th anniversary of the event, which included the opening of “Bulldog Lanes,” a renovated on-campus bowling alley built in symbolic response to the tragedy.

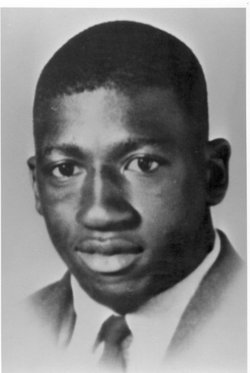

Samuel Hammond, age 18 years old, college student fatally shot during Orangeburg Massacre, ca. 1968, image courtesy of Cecil Williams.

Delano Middleton, age 18 years old, college student fatally shot during Orangeburg Massacre, ca. 1968, image courtesy of Cecil Williams.

Henry Smith, age 18 years old, college student fatally shot during Orangeburg Massacre, ca. 1968, image courtesy of Cecil Williams.

“The shootings occurred on February 8, 1968, two nights after an effort by students from an almost all all-black college to bowl at the city’s only bowling alley. The owner refused. Tensions rose and violence erupted.

When it ended, nine students and one city policeman received hospital treatment for injuries.

Other students were treated at the college infirmary. College faculty and administrators at the scene witnessed at least two instances where a female student was held by one officer and clubbed by another. In total, 28 students were injured and three were dead.

After two days of escalating tension, a fire truck was called to douse a bonfire lit by students on a street in front of the campus. State troopers—all of them white, with little training in crowd control—moved in to protect the firemen. As more than 100 students retreated inside the campus, a student tossed a banister rail which struck one trooper in the face. He fell to the ground bleeding. Five minutes later, almost 70 law enforcement officers lined the edge of the campus. They were armed with carbines, pistols and riot guns—short-barreled shotguns that by dictionary definition are used “to disperse rioters rather than to inflict serious injury or death.” But theirs were loaded with lethal buckshot, which hunters use to kill deer. Each shell contained nine to 12 pellets the size of a .32 caliber pistol slug.

As students began returning to the front to watch their bonfire go out, a patrolman suddenly squeezed several rounds from his carbine into the air—apparently intended as warning shots. As other officers began firing, students fled in panic or dived for cover, many getting shot in their backs and sides and even the soles of their feet.

Survivor Robert Lee Davis recalled in his oral history project interview: “The sky lit up. Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! And students were hollering, yelling and running. I went into a slope near the front end of the campus, and I kneeled down. I got up to run, and I took one step; that’s all I can remember. I got hit in the back.”

Later, Davis lay on the bloody floor of the campus infirmary, head to head with victim Samuel Hammond, a friend and quiet freshman halfback who was also shot in the back, and watched him die. Victim Henry Smith, a tall, slender ROTC student who had called his mother at two a.m. to tell her about the “shameful” beating of the female students by policemen, died after arriving at the hospital with five separate wounds. Victim Delano Middleton, a 200-pound high school football and basketball star whose mother worked as a maid at the college, died after asking her to recite the 23rd Psalm for him and then repeating it himself while lying on a hospital table with blood oozing from a chest wound over the heart.

Of 66 troopers on the scene, eight later told the FBI agents they had fired their riot guns at the students after hearing shots. Some fired more than once. A ninth patrolman said he fired his .38 caliber Colt service revolver six times as “a spontaneous reaction to the situation.” At least one city policeman—he later became police chief—fired a shotgun.

Sellers incarcerated:

Two and a half years after the shooting, a jury in Orangeburg convicted Cleveland L Sellers, Jr. of “inciting a riot” because of limited activity at the bowling alley two nights before the shooting. Sellers, who had grown up 20 miles from Orangeburg, had returned from the Deep South combat zone of the civil rights struggle as national program director for the militant Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The presiding judge threw out charges of conspiracy to riot and incitement to riot, but the charge of riot stood. He served seven months of a one-year sentence in state prison with early release for good behavior.

Sellers pardoned:

On July 20, 1993 the state’s Probation, Pardon, and Parole Board voted unanimously to pardon Sellers after a staff investigation recommended it. On the Sunday after Sellers’ pardon, South Carolina’s largest daily newspaper, “The State ” in Columbia, SC said in its lead editorial that the pardon “was long, long overdue,” but represented “a significant step toward reconciliation and the healing process.”

“Witnesses reported that students were unarmed and attempting to flee.”

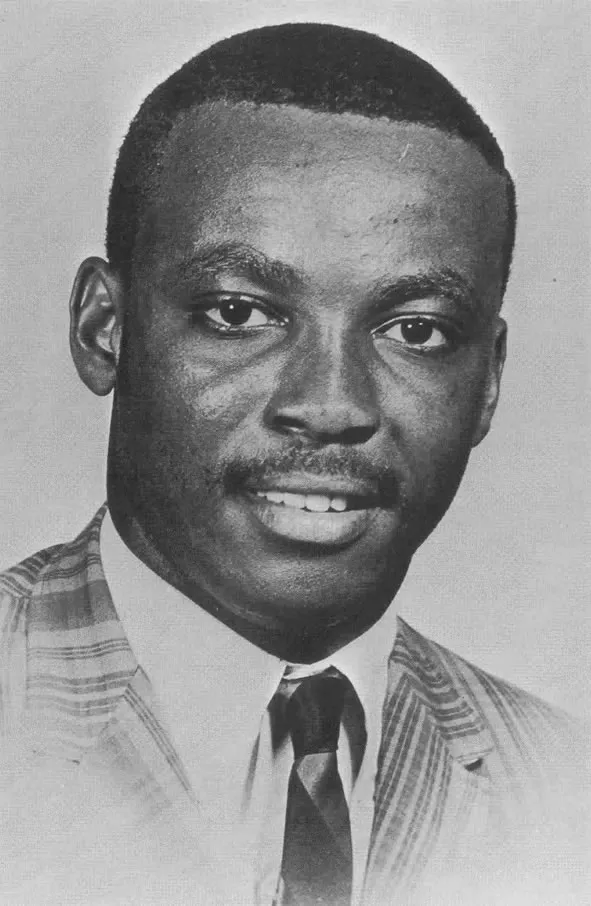

THE SURVIVOR

Robert Lee Davis

(often nicknamed “Big Dooley”) was a prominent survivor and eyewitness of the Orangeburg Massacre, which occurred on February 8, 1968, at South Carolina State College.

Decades later, the state issued a formal apology. The injustice exposed how southern states used violence to silence students demanding basic rights.

The Orangeburg Massacre remains a reminder of the cost of activism and the resilience of Black student leaders who refused to accept second-class citizenship.

His Role in the Massacre

-

The Shooting: Davis, a 260-pound football player at the time, was shot in the back by South Carolina Highway Patrol officers as he attempted to flee the campus bonfire.

-

Paralysis: The gunshot wound paralyzed him, and he was trampled by other students who were also fleeing the gunfire.

-

Final Moments with Samuel Hammond: While lying on the floor of the campus infirmary, Davis was positioned head-to-head with his friend and teammate, Samuel Hammond. He famously recounted Hammond asking him, “Dooley, do you think I’m going to live?” to which Davis replied, “Sam, you’re going to be alright, buddy.” Hammond died moments later, and Davis closed his friend’s eyes.

Advocacy and Legacy

-

Bowling Alley Protest: Before the shooting, Davis was one of the students denied entry to the All Star Bowling Lanes, an event that sparked the series of protests leading to the massacre.

-

Oral History: In later years, Davis became a key voice in ensuring the event was not forgotten. On the 33rd anniversary in 2001, he was one of eight survivors to publicly share his story as part of an oral history project.

-

Professional Life: Following the tragedy, Davis worked with emotionally disturbed children and remained a vocal advocate for the “ones that were actually involved” to tell the true story of what happened.