Black Broadway Theatre History ~ Our Moments and Circumstances

“B’Way Broadway The American Musical” Full Documentary [AI Enhanced] History of Musicals Mini Series

BLACK Broadway THEATRE ~ A Visual Artistic Journey *

https://iforcolor.org/wp-admin/post.php?post=16900&action=edit&classic-editor

Who was the first Black person to perform on Broadway?

Bert Williams in The Ziegfeld Follies, 1910

“Florenz Ziegfeld invited Williams to be a headliner in his Follies of 1910, making him the first Black to perform on Broadway as an equal alongside Whites.”

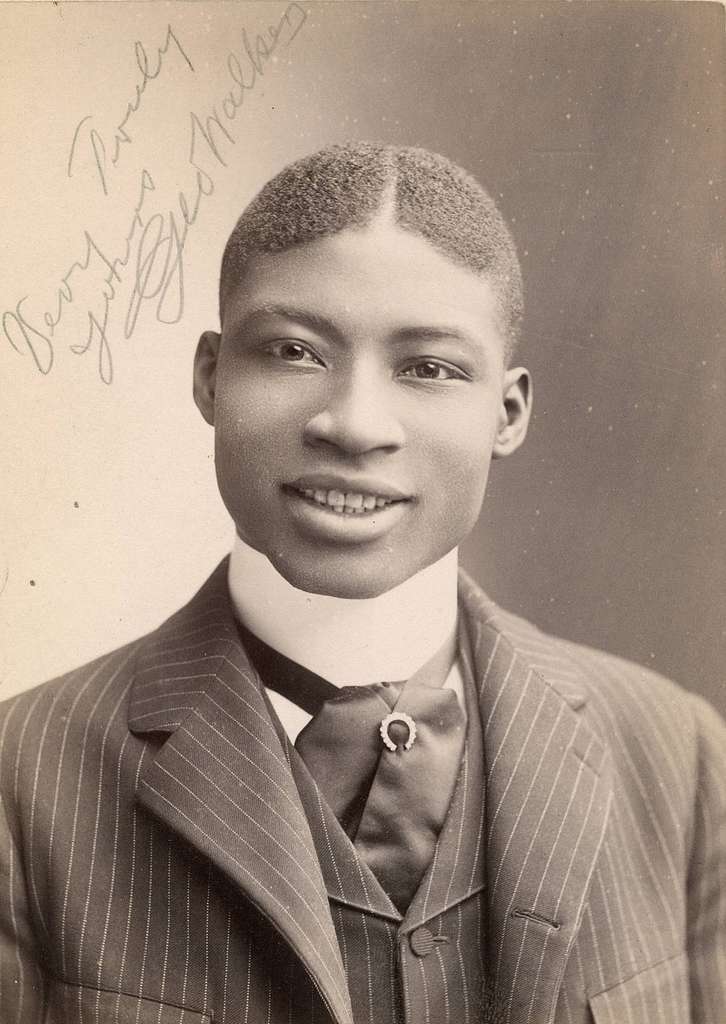

Bert Williams and George Walker

“At the turn of the twentieth century, Bert Williams and George Walker were two of the most sought after comedians on the American stage, renowned for their storytelling, singing, dancing, and pantomime.”

[“Williams was not allowed to join the Actors’ Equity Guild until W. C. Fields pressured the organization, despite the fact that at the time Williams’ salary was greater than that of the President of the United States.”]

GEORGE WALKER

Williams caricature by Marius de Zayas

~*~

Patrick Henry “Pat” Chappelle (January 7, 1869 – October 21, 1911) African-American theatre owner and entrepreneur, who established and ran The Rabbit’s Foot Company, a leading traveling vaudeville show in the first part of the twentieth century. Chappelle became known as one of the biggest employers of African Americans in the entertainment industry, with multiple tent traveling shows and partnerships in strings of theaters and saloons.

Chappelle was described at that time as the “Pioneer of Negro Vaudeville” and “the Black P. T. Barnum,” and was the only African American to fully operate a traveling show solely composed of African-American entertainers. Chappelle was born in Jacksonville, Florida, the son of Lewis Chappelle and his wife Anna, who had been slaves in Newberry County, South Carolina. After slavery was abolished, they left South Carolina with their relatives and other freed slaves to help construct the suburban neighborhood of LaVilla in Jacksonville, which became a center of African-American culture in Florida. Lewis Chappelle and his brother Mitchell Chappelle worked on house construction and also held several political positions in LaVilla. Their other brother Julius Caesar Chappelle, Pat’s uncle, also worked in construction in LaVilla and then moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where he became a legislator between 1883 and 1886, one of the early Black Republicans in Boston (the Republican Party was founded by abolitionists).

Pat Chappelle was musically gifted. He and his brothers and cousin learned musical skills from some of their relatives – Pat learned how to play the guitar and piano, but was best known for his proficiency in banjo. He left school after the fourth grade and played guitar in traveling string bands. He started playing in hotels on the East Coast and was discovered by a prestigious vaudeville circuit owner, Benjamin Franklin Keith, who offered him bookings with the Museum circuit in Boston and New York City. Later, he performed in Florida restaurants and saloons. In 1898, Chappelle returned to Jacksonville and organised his first traveling show, the Imperial Colored Minstrels (or Famous Imperial Minstrels), which featured comedian Arthur “Happy” Howe and toured successfully around the South. Early shows also featured ragtime pianist Prof. Fred Sulis, and White country music fiddler Blind Joe Mangrum (who went on to record for Victor Records as late as 1928). Chappelle also opened a pool hall in the commercial district of Jacksonville. Remodeled as the Excelsior Hall, it became the first Black-owned theater in the South, reportedly seated 500 people, and also sold whiskey. In an August 20, 1898 article in The New York Times, it was stated that Chappelle, who was standing outside the saloon in Jacksonville, was “almost beaten to death” by an angry mob who blamed him as the proprietor for a dosing of soldiers inside the saloon with “knockout drops” by unknowns that caused some of the men to appear “completely insensible, seemingly lifeless” and left other “almost screaming with pain and writhing in convulsions.”

Pat Chappelle’s life was saved by “Major Harrison, Provost Marshall, in ordering out a reserve guard.” The article also reported that Chappelle “was terribly beaten and kicked.” In 1899, following a dispute with the White landlord of the Excelsior Hall, J. E. T. Bowden, who was also the Mayor of Jacksonville, Chappelle closed the theatre and stripped out its tiled floor and fixtures. He moved to Tampa, where he – with fellow African-American entrepreneur R. S. Donaldson – opened a new vaudeville house, the Buckingham, in the Fort Brooke neighborhood, using the Excelsior’s fittings. The Tampa Morning Tribune reported that “he mayor of Jacksonville is therefore after Chappell, and there may develop an interesting local end to the story.” Chappelle claimed that he owned the fittings, but eventually they were returned to Jacksonville and the charges against him were dropped. The Buckingham Theatre’s Saloon opened in September 1899, and within a few months was reported to be “crowded to the doors every night with Cubans, Spaniards, Negroes and White people”. In December 1899 Chappelle and Donaldson opened a second theatre, the Mascotte, closer to the center of Tampa. In 1906, Chappelle launched travelling tent companies, the Funny Folks Comedy Company, managed by his cousin Mitchell P. Chappelle. The same performers, including Happy Howe and Cuba Santana, alternated between the two companies. As Pat Chappelle’s business expanded, a correspondent in The Freeman in 1908 stated that “Mr. Chappelle has no equal when it comes to managing these kind of shows… he has proven to be the black P. T. Barnum, when it comes to the success of a Negro show.” However, around 1907, his brothers Lewis and James quit working with Pat, after Pat expressed dissatisfaction with their work. Lewis went to work as a blacksmith and James became a horse caretaker. In August 1908, one of the Pullman Company railroad carriages used by Chappelle burned to the ground in Shelby, North Carolina, while several of the vaudeville entertainers were asleep. The accident happened after one of their nearby horses accidentally kicked over a tank of gasoline near a cooking stove.

The injured were taken to the Good Samaritan Hospital in Charlotte. One of the most severely injured was George Connelly, who had tried to save horses trapped in fire in a car stall; two of the horses died, but George saved one of them, and was mentioned as a hero by the media. Others who had escaped from the car unharmed still had to handle the loss of their clothes and other belongings, as well as the tragedy of the accident and those injured. Pat Chappelle was unharmed and quickly ordered a new carriage and eighty-foot round tent so the show could go on the following week. Financially, the tragedy costed him $10,000. He mentioned to The Freeman newspaper that the incident could have been prevented if there had been a fire department in the area, or at least water for a “bucket brigade.” In 1909, Chappelle sued the Mobile and Ohio Railroad which overcharged for the transportation of his Pullman sleeper and baggage cars. He also tried to gather support to help lower the transportation rates of the Southern Railroad Association, as the high rates targeted the tour show.

By 1910, Chappelle was suffering from an unspecified illness and his doctor told him to rest. He went with his wife Rosa to the countryside in Georgia. Pat returned to the tour but then left again in the winter of 1910; his brother Lewis took over some of the day-to-day operations, and his other brother James returned to work in ticketing. Despite Pat’s non-attendance at his show that year, it was still a success. Pat and Rosa traveled in Europe, one aim being to see the celebrations of the coronation of King George V in England in June 1911, and were on the RMS Lusitania, according to U.S. passenger records. Pat told The Freeman newspaper that he had enough money to retire, and announced that he would not take his show out that year due to his health. Pat Chappelle died in October 1911 at his home in LaVilla, aged 42. At his death, he was said to be “one of the wealthiest colored citizens of Jacksonville, Fla., owning much real estate”

Iforcolor.org 2025 – All Rights Reserved ©2021 – DRShields

- A Raisin In The Sun, Adrienne Warren, Andre De Shields, Anthony Ramos, Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu, Ariana DeBose, Aubrey Lyles, Audra McDonald, AUGUST WILSON, Aziza Barnes, Ben Vereen, Bert Williams, Beverly Jenkins, Billy Porter, Black Theatre Movement, Brandon Victor Dixon, Brian Stokes Mitchell, Camille A. Brown, Charles Gilpin, Charles Gordone, Charlie Smalls, Cheryl L. West, Chuck Cooper, Cicely Tyson, Cleavon Little, Cynthia Erivo, Dale Ricardo Shields, Dale Shields, Daveed Diggs, Day of Absence, Diahann Carroll, Douglas Lyon, Douglas Turner Ward, Drew Shade, DYLAN PARENT, Ephraim Sykes, Eubie Blake, Flournoy Miller, Frank Wilson, Geoffrey Holder, George C. Wolfe, George Faison, Gregory Hines, Harlem Renaissance, Harry Belafonte, Irene Gandy, James Earl Jones, James Hewlett, JANICE SIMPSON, Jean Genet, Jennifer Holliday, Jeremy O. Harris, Jeremy Pope, Joseph Papp, Joshua Henry, Juanita Hall, Keenan Scott II, Ken Harper, Kenny Leon, Langston Hughes, Leslie Odom Jr., Leslie Uggams, Lisa Nocella-Pacino, Lloyd Richards, Lorraine Hansberry, Louis Johnson, Lynn Nottage, Marc J. Franklin, Maurice Hines, Melba Moore, Michael R. Jackon, Micki Grant, Miguel Pinero, New Federal Theatre, Noble Sissle, Ntozake Shange, Paul Green, Paul Robeson, Pearl Bailey, Perry Watkins, Porgy and Bess, Raul Julia, Renée Elise Goldsberry, Richard Wesley, Robert Hooks, Robert Nemiroff, Roger Robinson, Rose McClendon, Ruben Santiago-Hudson, Savion Glover, Stew Rodewald, Suzan-Lori Parks, Tarell Alvin McCraney, THE AFRICAN GROVE THEATRE, The American Negro Theatre, The Blacks, THE DANCE THEATRE OF HARLEM, The Negro Ensemble Company, The Scottsboro Boys, Tom O'Horgan, uzan-Lori Parks, Vinnette Carroll, Walter Dallas, Woodie King Jr.

iforcolor

ARCHIVIST, EDUCATOR, HISTORIAN, and ARTiST

Dale Ricardo Shields is highly accomplished African American actor, director, producer, and educator with a distinguished career in theatre and academia.

Here's a summary of his background and achievements:

Early Life and Family:

Born on November 4, 1952, in Cleveland, Ohio.

His family has a strong musical background; his grandfather and father were founding members of the Shields Brothers Gospel Quartet of Ohio, and his mother was part of the Turner Gospel Singers.

He is a cousin of boxing promoter Don King.

Education:

Graduated from John F. Kennedy High School in 1970.

Holds both a BFA (1975) and MFA (1995) from Ohio University.

Career and Contributions

Theatre Professional:

Actor: Has appeared on Broadway, Off-Broadway, Off-Off-Broadway, and in regional productions. His television credits include The Cosby Show, Another World, Guiding Light, Saturday Night Live, and the ITV series Special Needs. He has also appeared in commercials and films.

Director and Stage Manager: Has extensive professional credits in these roles, including projects at Lincoln Center, The Henry Street Settlement House (New Federal Theatre), The Negro Ensemble Company, and The Joseph Papp Public Theatre.

Assistant Director: Served as assistant to Lloyd Richards and assistant director for the New Federal Theatre premiere of Ossie Davis's play A Last Dance With Sybil starring Ruby Dee and Earl Hyman.

Educator:

Professor: He is a Professor of Acting, Directing, Black Theatre, Black Studies, and Stage Management. He has taught at various institutions, including Ohio University, The College of Wooster, Denison University, Macalester College, Susquehanna University (as artist-in-residence), and SUNY Potsdam.

Workshops and Programs: Conducted workshops for Joseph Papp's Playwriting in the Schools Program (PITS) at The Public Theatre for six seasons and represented the United States at the ASSITEJ Theatre Festival in London, England, in 1988.

Artistic Activist and Historian:

Iforcolor.org: Creator and archivist for the Black History website Iforcolor.org, dedicated to preserving and sharing information about African Americans and artists of color. He also maintains the "Black Theatre/African American Voices" website on Facebook.

Project1VOICE Liaison: Serves as the Project1VOICE Liaison for the state of Ohio, directing "One Play One Day" events in Cleveland since 2011.

Awards and Recognition:

The Kennedy Center/Stephen Sondheim Inspirational Teacher Award: Recipient in 2017.

Paul Robeson Award: Recipient in 2021 (jointly presented by the Actors' Equity Association and Actors' Equity Foundation).

AUDELCO/"VIV" Special Achievement Award: Received in 2017.

Tony Award Nominee: Nominated for the "Excellence in Theatre Education Award" in 2015 and 2017.

Ebony Bobcat Network (EBN) Legend Award: Received from Ohio University in 2022.

ENCORE AWARD / The Actors Fund: Received in 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2024.

Outstanding Professor Awards: Has received two of these and three "Educational Program of the Year" awards as a university professor.

The HistoryMakers archives: Interviewed and included in The HistoryMakers archives, permanently housed in the Library of Congress.

Dale Ricardo Shields is recognized for his profound impact on the lives of his students and his unwavering dedication to preserving and promoting Black theatre history and culture.