FANNIE LOU HAMER

https://www.goodmantheatre.org/show/fannie/

✨ National Women’s History Month.

“Celebrating Women Who Tell Our Stories”

by DALE RICARDO SHIELDS

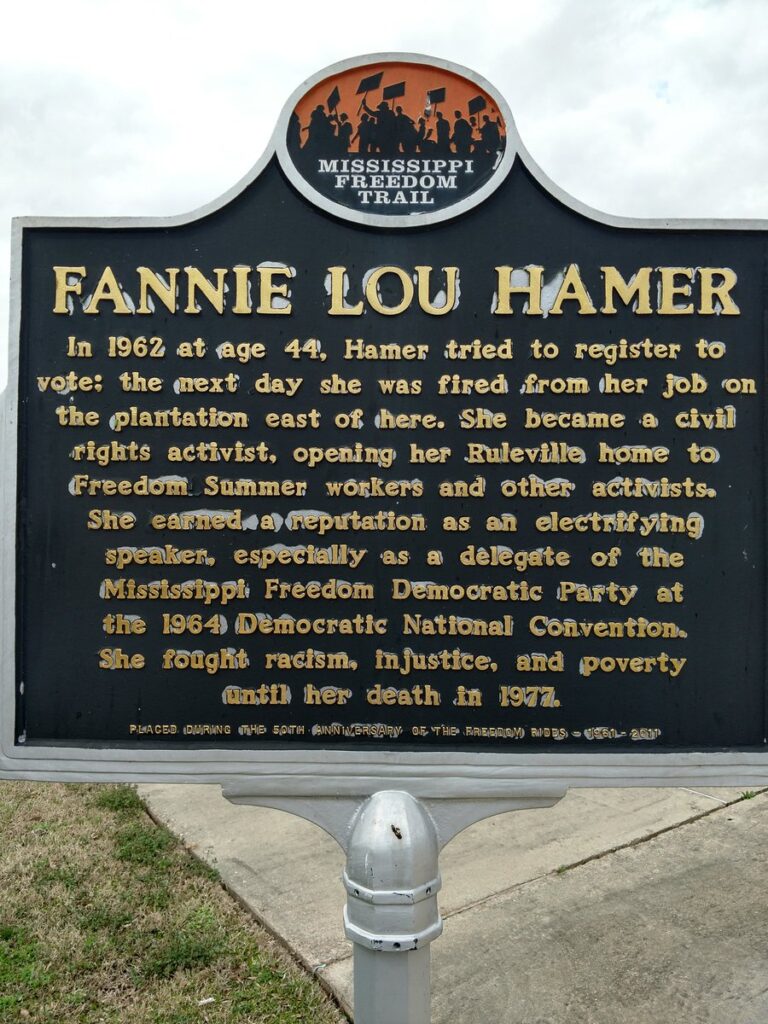

American voting and women’s rights activist, community organizer, and leader in the civil rights movement. She was the vice-chair of the Freedom Democratic Party, which she represented at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. – [Wikipedia]

Born: October 6, 1917, Montgomery County, MS

Died: March 14, 1977, Taborian Hospital, Mound Bayou

Albums: The Songs My Mother Taught Me

Party: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

Organizations founded: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Freedom Farm Cooperative, and National Women’s Political Caucus.

*~*

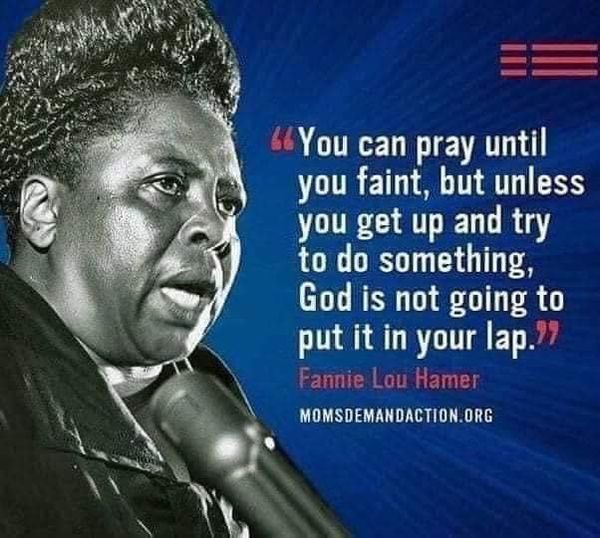

10 Hamer QUOTES

1. “Sometimes it seem like to tell the truth today is to run the risk of being killed. But if I fall, I’ll fall five feet four inches forward in the fight for freedom. I’m not backing off.“

2. “When I liberate myself, I liberate others. If you don’t speak out ain’t nobody going to speak out for you.“

3. “Never to forget where we came from and always praise the bridges that carried us over.“

4. “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.“

5. “We didn’t come all the way up here to compromise for no more than we’d gotten here.“

6. “Righteousness exalts a nation. Hate just makes people miserable.“

7. “We have to build our own power. We have to win every single political office we can, where we have a majority of Black people...”

8. “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.“

9.”Hate won’t only destroy us. It will destroy these people that’s hating as well.“

10. “There is one thing you have got to learn about our movement. Three people are better than no people.”

*~*

Ms. Hamer, thank you for paving the way for Black voting rights. Your fearlessness and powerful legacy remain an inspiration to us all.

“The youngest of her parents’, Ella and James Lee Townsend’s, 20 children. Her family moved to Sunflower County, Mississippi in 1919 to work on the plantation of W. D. Marlow as a sharecropper. Hamer picked cotton with her family, starting at the age of 6. She attended school in a one-room schoolhouse on the plantation, from 1924-1930, at which time, she had to drop out. By the age of 13, Hamer could pick 200-300 pounds of cotton daily. In 1944, after the plantation owner discovered that she was literate, Hamer was selected to be the plantation’s time and record keeper. In 1945 she married her husband, Perry “Pap” Hamer. They worked together on the plantation for the next 18 years.

During the 1950s, Hamer attended several annual conferences of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL) in the all-Black town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi. The RCNL, a combination of civil rights and self-help organization, was led by Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a civil rights leader, and wealthy Black entrepreneur. The annual RCNL conferences featured entertainers such as Mahalia Jackson, speakers such as Thurgood Marshall and Rep. Charles Diggs of Michigan, and panels on voting rights and other civil rights issues.

While having surgery to remove a tumor, in 1961 Hamer was also given a hysterectomy without her consent by a white doctor as a part of the state of Mississippi’s plan to reduce the number of poor Blacks in the state. The Hamers later raised two impoverished girls, who they later decided to adopt.”

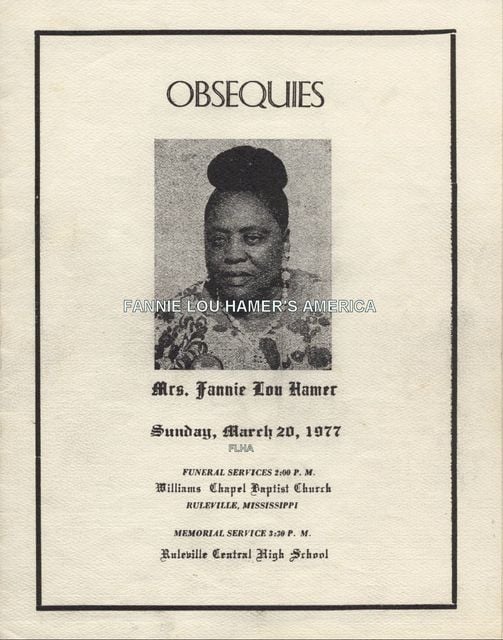

At 5 pm, on Monday, March 14, 1977, activist and humanitarian Fannie Lou Hamer closed her eyes for the very last time. Hamer had been hospitalized for complications related to heart disease, diabetes, and breast cancer. The once powerful and passionate proponent of equal rights that so many turned to for help, was now unable to comb her own hair. The throngs of people she’d helped over the years dwindled to a trickle as she spent her last days in a hospital in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. Pap, her loving and dedicated husband, already struggling financially with her mounting medical bills, was willing to pay people to come and visit his dying wife. Her good friends Martha Smith and June Johnson also reached out, begging people to help…but that help never came. But Fannie Lou Hamer’s legacy lives on. What she accomplished during her lifetime, helping thousands to register and vote, and providing jobs, educational opportunities, food, clothing and shelter for the poor will never be forgotten. (Fannie Lou Hamer: Oct. 6, 1917 – March 14, 1977) https://www.fannielouhamersamerica.com/…/loss-of-an-icon – [ Courtesy of Laura Heller and the Fannie Lou Townsend Hamer Collection (T/012), Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection, MDAH. ]

Death

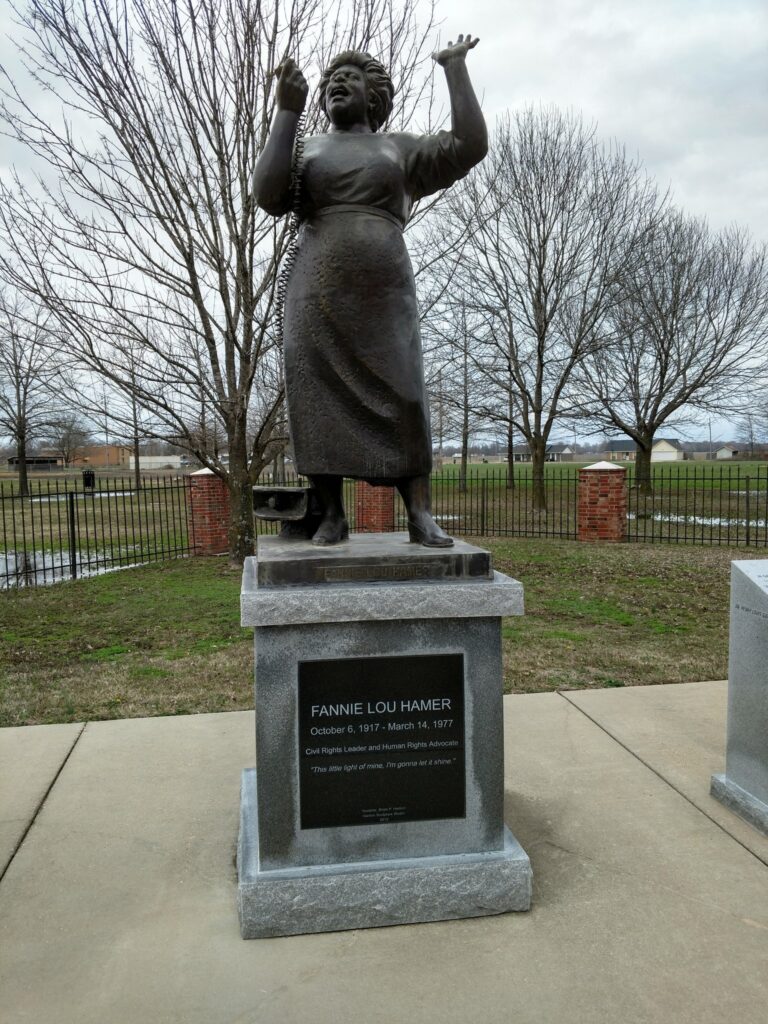

Hamer died of heart failure due to hypertension on March 14, 1977, at the age of 59 at a hospital in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, and was buried in her hometown of Ruleville, Mississippi. Her tombstone is engraved with one of her famous quotes…

Did you know? Fannie Lou Hamer’s tombstone in her hometown of Ruleville, Mississippi is inscribed with her famous quote, “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Flickr – Mississippi Authority

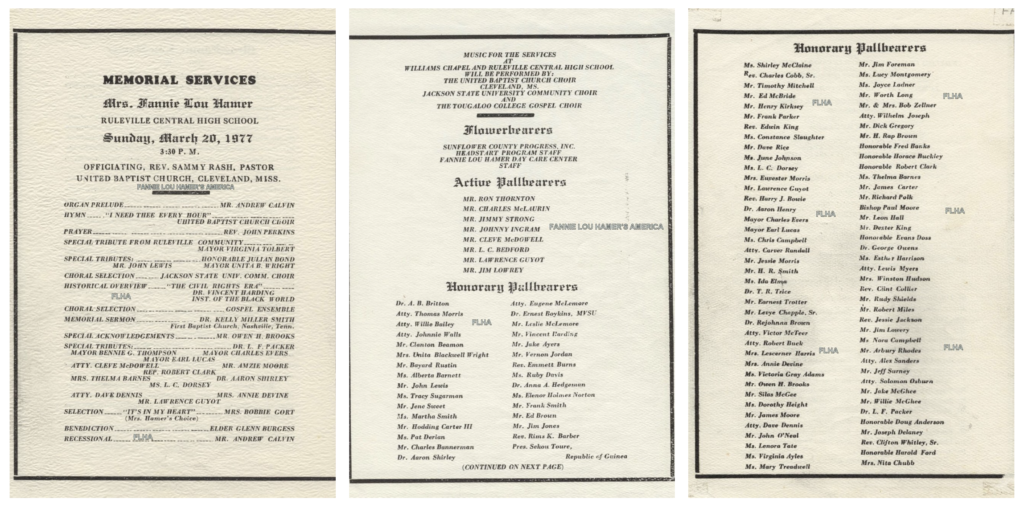

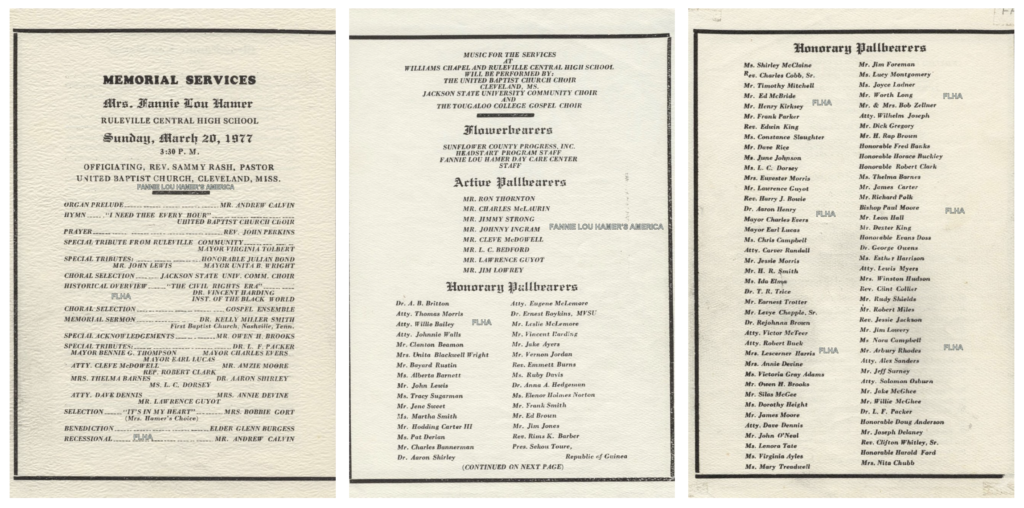

Her primary memorial service, held at a church, was completely full. An overflow service was held at Ruleville Central High School, with over 1,500 people in attendance. Andrew Young, the United States Ambassador to the United Nations at that time, spoke at the RCHS service.

Loss Of An Icon

Monday, March 14, 1977

Always the consummate advocate for one cause or another, Fannie Lou Hamer’s highly physical and emotional mission was finally taking its toll on her. As the fall of 1971 turned into the winter of 1972, Hamer slowly began to withdraw. She had long suffered from the effects of the savage beating she received at the hands of law enforcement officials in a Winona, MS jail cell. That assault left her with permanent kidney damage, backaches, headaches, and severely compromised eyesight. But the pain and exhaustion she experienced during the last winter months suggested that something else was wrong. The unbearable physical pain combined with psychological worry – rooted in a lifetime of trauma – kept Hamer up at night and in bed most of the day.

Then one afternoon in late January 1971, cold sweat trickled from her forehead as she squinted against the winter sun’s glare. She had organized a boycott of a local store where the owner had kicked a young Black girl in the back. The boycott had gone on for two weeks, and Hamer supported her Black community in Ruleville in the boycott and demonstrations, despite the fact that she grew weaker and dizzier day by day. Suddenly, the picket line chants faded into the background and her legs became numb. Fannie Lou Hamer slowly fell to the pavement with her fellow demonstrators rushing to her side. Tattered handkerchiefs mopped her soggy brow. Concerned faces crowded her vision. Her husband, Pap, soon arrived and took his wife to the Tufts-Delta Community Health Center in Mound Bayou, MS. Her heart rate slowed down a bit, and she was finally able to take deeper breaths. Pap wheeled her inside where she was examined by a doctor. In the midst of their panic, Pap and Fannie Lou Hamer tried to focus as the doctor explained to the shaken couple the symptoms of nervous exhaustion.

The medical professionals ran tests and listened carefully as Hamer described her fatigue, blurred vision, aches, pains, and feelings of frustration, hopelessness, and despair. Running her beloved Freedom Farm; campaigning for the State Senate; traveling and speaking nationally, while caring for, Jacqueline (Cookie) and Lenora (Nook) – then just five and six-years-old was wearing her down. Through a culmination of disappointments, including: the sudden and untimely death of her good friend and Freedom Farm manager, Joe Harris; her own frequent hospital visits, or the cancerous lump she had discovered in her left breast, but ignored – by her late fifties, Fannie Lou Hamer sensed the end was near.

In the early winter months of 1977, she was admitted to the Tufts-Delta Community Health Center in Mound Bayou for the last time. She was being treated for complications related to heart disease, diabetes and breast cancer.

Sadly, the steady stream of visitors that had consistently knocked on her door or pleaded for her help or advice had slowed to a trickle as her health continued to fail. Her husband, Pap, lamented that the only way he could get people to come and visit his ailing wife was if he paid them. And he had no money to do that having lost his job with Head Start when the federal operation downsized its outreach in the Mississippi Delta.

Hamer’s friends and family remembered how she grew increasingly agitated as her condition worsened. June Johnson, the young woman who was jailed and beaten in Winona with Hamer when she was 15-year-old in 1963 – visited frequently and sometimes found her dear friend in tears and at other times in a confused mental state. During one visit, Johnson recalled how Hamer had sent for a neighbor to come help comb her hair and hours had gone by – and no one showed to help her. Johnson comforted Hamer by gently combing and setting her friend’s now thinning strands of hair.

Both Johnson and Measure for Measure leader, Martha Smith, knew Hamer would not live much longer. In a letter she wrote to Hamer’s “friends, brothers and sisters,” Johnson sounded the alarm that Hamer was “seriously ill with cancer.” Johnson pleaded for them to come to Hamer’s “bedside, or send cards, letters and donations” for her “medical expenses” and to support her children.

Smith, who had also visited Hamer in Mound Bayou in early March 1977, penned an emergency memorandum to Measure for Measure supporters, who for years had come to Hamer’s aid in helping the poor within the Delta community. Smith likewise appealed for funds to help with Hamer’s mounting medical bills and family responsibilities.

Within her memo, Smith expressed how “very hard” it was for her to “see such a strong, generous, and idealistic woman lying helpless, hopeless, broken and broke.”

“If you feel you can help out with this crying and urgent need please send a check to Measure for Measure – earmarked the Fannie Lou Hamer Fund,” Smith wrote.

But before Smith’s urgent plea for help could ever reach the mailboxes of Measure for Measure supporters, Fannie Lou Hamer was gone. According to her death certificate, Fannie Lou Hamer died at 5 pm, on Monday, March 14, 1977. She was 59-years-old.

– Content taken from Fannie Lou Hamer: America’s Freedom Fighting Woman written by Dr. Maegan Parker Brooks

Courtesy of Laura Heller and the Fannie Lou Townsend Hamer Collection (T/012), Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection, MDAH.