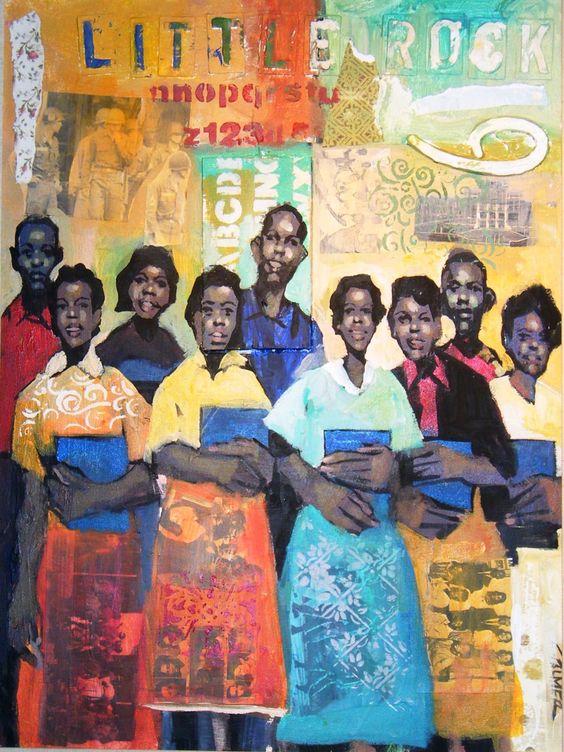

The Little Rock Nine

They Only Wanted To Go To School…

Thelma Mothershed, Elizabeth Eckford, Melba Pattillo,

Jefferson Thomas, Ernest Green, Minnijean Brown,

Carlotta Walls, Terrence Roberts, Gloria Ray.

By Dale Ricardo Shields

Little Rock, Arkansas

September 4, 1957

The original plan was to have the nine children arrive together, but when the meeting place was changed the night before, the Eckford family’s lack of a telephone left Elizabeth uninformed of the change. Instructions were given by Daisy Bates, a strong activist for desegregation, for the nine students to wait for her so that they could all walk together to the rear entrance of the school. This last-minute change caused Elizabeth to be the first to take a different route to school, walking up to the front entrance completely alone. Elizabeth Eckford’s family was not informed of the meeting and didn’t know that the school board asked the parents to accompany her.

Also, Eckford rode a public bus alone to the segregated school. That day, Elizabeth wore a starched black-and-white dress, and she covered her face under black sunglasses. Elizabeth also held her school book in her hand. As she walked toward the school, Elizabeth was surrounded by a crowd of armed guards and a mob of people, and she did not see any black faces. The mob included men, women, and teenagers (white students) who opposed integration. Elizabeth attempted to go into the school through the mob but was denied entrance. Eckford walked to a bus bench at the end of the block. Eckford described her experience:

Transcript

I’m Elizabeth Eckford. I am part of a group that became known as the Little Rock Nine. Prior to the desegregation of Central, there had been one high school for whites, Central High School, and one high school for blacks, Dunbar.

I expected that there may be something more available to me at Central that was not available at Dunbar, that there might be more courses I could pursue, and that there were more options available. I was not prepared for what actually happened.

I was more concerned about what I would wear, and whether we could finish my dress in time. What I was wearing, was that OK? Would I look good?

The night before, the governor went on television and announced that he had called out the Arkansas National Guard. I thought that he had done this to ensure the protection of all the students.

We did not have a telephone. So inadvertently, we were not contacted to let us know that Daisy Bates of NAACP had arranged for some ministers to accompany the students in a group and so it was I who arrived alone.

On the morning of September 4, my mother was doing what she usually did. My mother was making sure everybody’s hair looked right and everybody had their lunch money and other things, their notebooks and things. But she did finally get quiet, and we had family prayer.

I remember my father walking back and forth. My father worked at night, and normally, he would have been asleep at that time. But he was awake, and he was walking back and forth, chomping on a cigar that wasn’t lit.

I expected that I would go to school as before on a city bus. So I walked a few blocks to the bus stop, got on the bus, and rode to within two blocks of the school. Got off the bus, and I noticed along the street that there were many more cars than usual, and I remember hearing the murmur of a crowd.

But when I got to the corner where the school was, I was reassured, seeing these soldiers circling the school grounds. And I saw students going to school. I saw the guards break ranks as a student approached the sidewalk so that they could pass through to get to school. And I approached the guard at the corner as I had seen some other students do, and they closed ranks.

So I thought, well, maybe I am not supposed to enter at this point. So I walked further down the line of guards to where there was another sidewalk, and I attempted to pass through there. But when I stepped up, they crossed rifles.

And again, I said to myself, well, maybe I’m supposed to go down to where the main entrance is. So I walked toward the center of the street. And when I got to about the middle and I approached the guard, he directed me across the street into the crowd.

It was only then that I realized that they were barring me, and that I wouldn’t go to school. As I stepped out into the street, the people who had been across the street started surging forward behind me, and so I headed in the opposite direction to where there was another bus stop. Safety, to me, meant getting to that bus stop.

I feel like I sat there for a long time before the bus came. In the meantime, people were screaming behind me, what I would have described as a crowd before, to my ears sounded like a mob.

[INDISTINCT YELLING]

[CHANTING] Two, four, six, eight, we don’t wanna integrate! Two, four six, eight, we don’t wanna integrate!

Lynch her!

Lynch her!

We don’t wanna integrate!

Photo: FPG/Archive Photos (Getty ImagesS

SEPTEMBER 4, 1957

“When Dorothy Counts was spat on by the mob as she was trying to go to school, that was the day I decided I was coming home (from Baldwin’s self-imposed in Europe). And I came home, you know, to see, you know, to do whatever I could do. And I went south, and I began to deal with the reality, which had always been incipient in me but never been expressed or objectified. I fell in love with those people. And I was very happy to be in the South, even though it was very frightening. Something in me —- something in me recognized it. Something in me had come home.” – James Baldwin (Karen Thorsen’s documentary “The Price of the Ticket)

“At 15 years of age, on 4 September 1957, Dorothy Counts was one of the four Black students enrolled at various all-White schools in the district; She was at Harry Harding High School, Charlotte, North Carolina. Three students were enrolled at other schools, including Central High School. The harassment started when the wife of John Z. Warlick, the leader of the White Citizens Council, urged the boys to “keep her out” and at the same time, implored the girls to spit on her, saying, “spit on her, girls, spit on her.”Dorothy walked by without reacting but told the press that many people threw rocks at her—most of which landed in front of her feet—and that many spat on her back. Photographer Douglas Martin won the 1957 World Press Photo of the Year with an image of Counts being mocked by a crowd on her first day of school. More abuse followed that day. She had trash thrown at her while eating her dinner and the teachers ignored her. The following day, she befriended two White girls, but they soon drew back because of harassment from other classmates. Her family received threatening phone calls and after four days of extensive harassment—which included a smashed car and having her locker ransacked, her father decided to take his daughter out of the school.”

Charly Palmer (Artist)

THE LITTLE ROCK NINE – DALE RICARDO SHIELDS (IFORCOLOR Collective)

In the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision, issued May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation of America’s public schools was unconstitutional.

The Little Rock Nine was a group of nine African American students who volunteered to desegregate the Little Rock County school system by attending the all-White Little Rock Central High School.

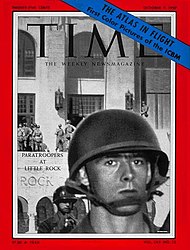

Their attendance at the school was a test of Brown v. Board of Education, a landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. On September 4, 1957, the first day of classes at Central High, Governor Orval Faubus called in the Arkansas National Guard to block the Black students’ entry into the high school. Later that month, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent in federal troops to escort the Little Rock Nine into the school.

Young U.S. Army paratrooper in battle gear outside Central High School, on the cover of Time magazine – (October 7, 1957)

Federal “battle” troops stand with rifles ready to quell “mob rule” in Little Rock resulting from the integration crisis at Central High School. These soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division took up their positions around the school again this morning, with renewed vigor after being relieved for the night by the Federalized Arkansas National Guard. The nine Negro students who entered the school under troop protection yesterday were again given portal-to-portal protection to school today.

10/9/1957-Little Rock, AR: Nine Negro students attending Central High School are shown leaving the school under the protection of Federalized Arkansas National Guardsmen. The students are now in their third week of integrated classes while the integration dispute continues to make headlines.

Getty Images)

“National Guard denied Black students from September 4th. Access to the school Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division advance into Little Rock to ensure the schooling of the Black students.”