“Police violence against Black people is the norm, not an outlier in the U.S.”

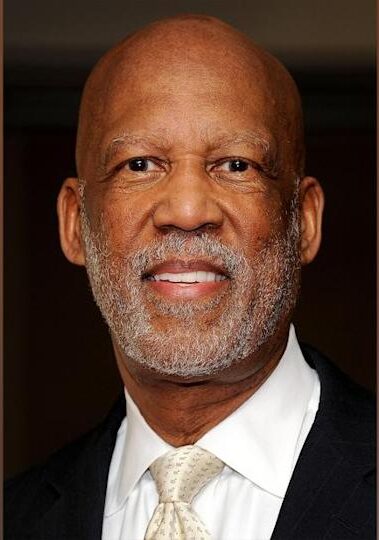

Minnijean Brown-Trickey

“I’ve just been so sad about whether my life was worth anything because it doesn’t seem like things have changed, and I’m sure a lot of people feel that way,” Brown-Trickey said from her home in Vancouver, British Columbia. “I got pushed back to Emmett Till, and growing up in Jim Crow, and Central (High School) and being arrested as an environmentalist. Every aspect of my life has just come forward and it’s just sorrow.”

Other members of the tight-knit Little Rock Nine echoed her sentiments.

Courtesy Spirit Trickey

“After 78 years of life, in all these years of fighting the same battle, what am I doing? Isn’t it supposed to be better than this?” said Melba Patillo Beals from her home in San Francisco.

But for Terrence Roberts, another member of the group, the turmoil surrounding George Floyd’s death is predictable. He doesn’t see today’s protests as a new era but as ongoing warfare.”

LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS – SEPTEMBER 13: Elizabeth Eckford poses for a portrait on September 13, 2007, in front of the main entrance of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Threading her way through an angry mob as the Arkansas National Guard looked on, Eckford was the first of nine Black schoolchildren to make history on September 4th, 1957 when she arrived, alone, for the first day of classes at the all-white high school. (Photo by Charles Ommanney/Getty Images)

(Photo by Charles Ommanney/Getty Images)

(Photo by Charles Ommanney/Getty Images)

“After 78 years of life, in all these years of fighting the same battle, what am I doing? Isn’t it supposed to be better than this?” said Melba Patillo Beals from her home in San Francisco.

But for Terrence Roberts, another member of the group, the turmoil surrounding George Floyd’s death is predictable. He doesn’t see today’s protests as a new era but as ongoing warfare.

“You can’t separate it into time periods, as if it’s changed,” said Roberts. “It hasn’t.”

Roberts, 79, a former assistant dean at UCLA, has continual conversations about race with his daughters and grandchildren, now teenage boys. To move forward, he said he believes the country must make a serious commitment to education.

“Human beings have the capacity to choose to change. We could do it if we wanted, we just haven’t mustered the will to do it,” Roberts said. “If what you already know hasn’t moved you to change, then change what you know.“

Brown-Trickey believes national outrage over Floyd’s death is not enough. As a social rights activist who teaches children non-violence through speeches and seminars across the world, she rails against the United States’ “rotten education” system mired in inequality.

“There doesn’t seem to be national shame about social conditions in this country,” she said.

Daily images of police pushing back protesters with excessive force have also resulted in a surge of traumatic memories for some members of the Little Rock Nine.

Patillo Beals still bears scars from assaults she endured from classmates. She vividly remembers having acid thrown in her eyes while at school. These memories have been hard to dismiss recently.

She points to President Donald Trump’s recent tweet that protesters “would have been greeted with the most vicious dogs, and most ominous weapons, I have ever seen” had they breached the White House fence.

“Come on over the fence, and we’ll use dogs’ — really?” she said. “I heard that when I was 8. I heard that when I was 7. I heard that when I was 6.”

But the Little Rock Nine see stark differences between the Floyd protests and what they experienced more than 60 years ago. Social media, they say, has allowed today’s activists to quickly coalesce and spread their message.

“We didn’t have Facebook, and we didn’t have social media,” Brown-Trickey said. “You can cast a wider net for people to listen and participate.“

Added Patillo Beals: “What’s different is the variety of people at those marches, and that is sweet sunshine from heaven to me,” she said.

What hasn’t wavered for Patillo Beals is where true power lies: political representation. She wants to see voter registration tables alongside protesters.

“Your marching gets you the attention, but you’re better off if you back it up with something,” she said, referring to voting.

Despite violent police crackdowns on protesters, Little Rock Nine members see rays of hope amid the turmoil roiling the country.

Carlotta Walls LaNier, the youngest member, lauds the global attention cast on today’s protesters. For six decades she has held onto letters of support she received from across the world — from Denmark and Africa and other places — when the Little Rock Nine made headlines.

“I have hope. We have support around the world. The support from people around the world helped us (in 1957),” LaNier said.

Patillo Beals said she also finds images of hope in the unrest.

“I am impressed by the numbers. I hate that the numbers come when we face Covid, but the numbers are there, clearly, when you look to Oregon and you see all of these people marching over that bridge,” Patillo Beals said. “That to me says this is a wake-up call, and more people woke up this time than before.”

Little Rock Nine members question how far we’ve come, 63 years after they broke a racial barrier.”

https://www.kmov.com/news/little-rock-nine-members-question-how-far-weve-come-63-years-after-they-broke-a/article_79a1f5b7-d12a-57d1-9832-71a1f81a878f.html

Lawyer Thurgood Marshall and civil rights activist Daisy Bates join several members of the “Little Rock Nine”, the first students to integrate Central High School.

New York City Mayor Robert Wagner greeting the Little Rock Nine.

Pictured, front row, left to right: Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Carlotta Walls, Mayor Wagner, Thelma Mothershed, Gloria Ray; back row, left to right: Terrence Roberts, Ernest Green, Melba Pattillo, Jefferson Thomas.

IMAGE / Mr. Walter Albertin via WikimediaCommons

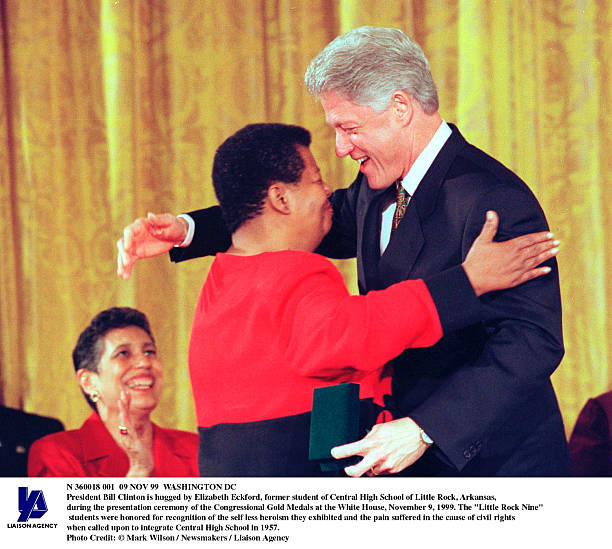

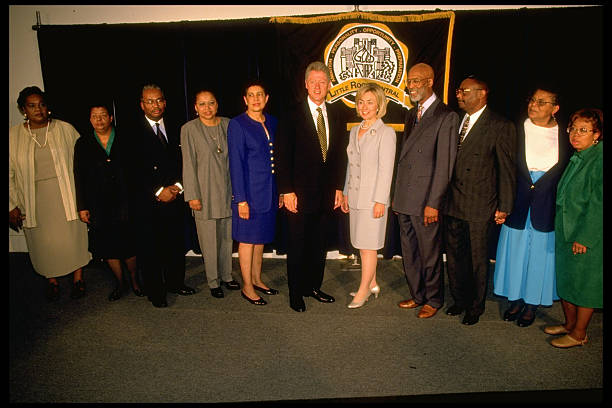

All of the Little Rock Nine members were given the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) in 1958 and the Congressional Gold Medal from President Bill Clinton in 1999.

President Bill Clinton is hugged by Elizabeth Eckford, a former student of Central High School of Little Rock, Arkansas, during the presentation ceremony of the Congressional Gold Medals at the White House, November 9, 1999. The “Little Rock Nine” students were honored for the recognition of the selfless heroism they exhibited and the pain suffered in the cause of civil rights when called upon to integrate Central High School in 1957. (Photo by Mark Wilson)

WASHINGTON, : US President Bill Clinton (R) hugs Elizabeth Eckford (L) during the presentation of the Congressional Gold Medal to the members of the Little Rock Nine 09 November 1999, in the East Room of the White House. Eckford was the 15-year-old girl whose image, seen walking through a screaming mob in front of Central High School, propelled the crisis to a national level. The Little Rock Nine received the award for their sacrifice for the cause of civil rights when they integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. (ELECTRONIC IMAGE) AFP Photo by Paul J. Richards (Photo credit should read PAUL J. RICHARDS/AFP via Getty Images)

Pres. Bill Clinton on the Little Rock Nine & impact 60 years later

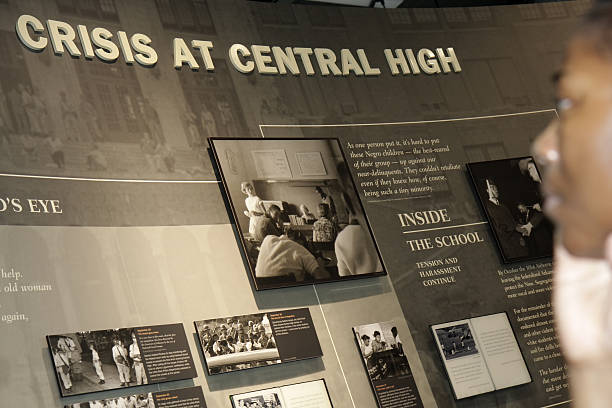

Crisis at Central High exhibit. (Photo by: Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Central High School National Historic Site sign. (Photo by: Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

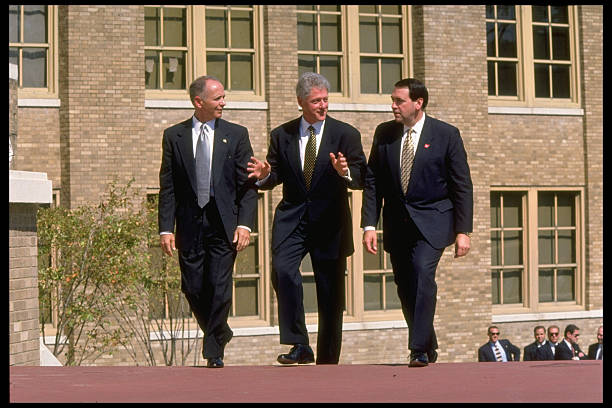

Pres. Bill Clinton (C) chatting w. Gov. Mike Huckabee (R) outside Central High during an event marking the return of Little Rock Nine, 1st black students to attend school in 1957. (Photo by Cynthia Johnson/Getty Images)

(L-R) Little Rock Nine vets Beals, Eckford, Green, Karlmark, Lanier, Pres. Clinton & McKindra, in the ceremony marking the return of 1st Black students to attend Central High in 1957. (Photo by Cynthia Johnson/Getty Images)

(L-R) Melba Pattillo Beals, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Carlotta Walls Lanier, Pres. Clinton, McKindra, Krupitsky, Mrs. Clinton, Roberts, Thomas, Brown Trickey & Mothershed Wair in return of Little Rock Nine, 1st black students to attend Central High, in 1957. (Photo by Cynthia Johnson/Getty Images)

Pres. & Mrs. Clinton (C) w. Little Rock Nine (L-R) Eckford, Green, Karlmark, Lanier, Roberts, Thomas, Brown Trickey & Mothershed Wair at the event marking the return of 1st black students to attend Central High in 1957. (Photo by Cynthia Johnson/Getty Images)

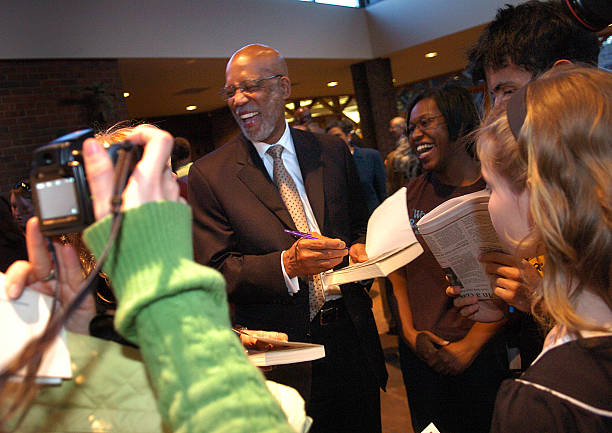

(HR) ABOVE: Terrence Roberts signs autographs for eager fans after the interfaith service at Congregation Emanuel. The nine members of what is now called the Little Rock Nine came together for only the 5th time in 50 years at Congregation Emanuel for an interfaith gathering. In 1957, nine ordinary teenagers walked out of their homes and stepped up to the front lines in the battle for civil rights for all Americans. The media coined the Little Rock Nine to identify the first African-American students to desegregate Little Rock Central High School. On September 3, 1957, the Little Rock Nine arrived to enter Central High School but were turned away by the Arkansas National Guard. The Little Rock Nine are Terrence Roberts, Minnijean Brown Trickey Elizabeth Eckford Ernest Green Thelma Mothershed Wair, Melba Pattillo Beals, Carlotta Wall LaNier, Jefferson Thomas, and Gloria Ray Karlmark. Helen H. Richardson/The Denver Post (Photo By Helen H. Richardson/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

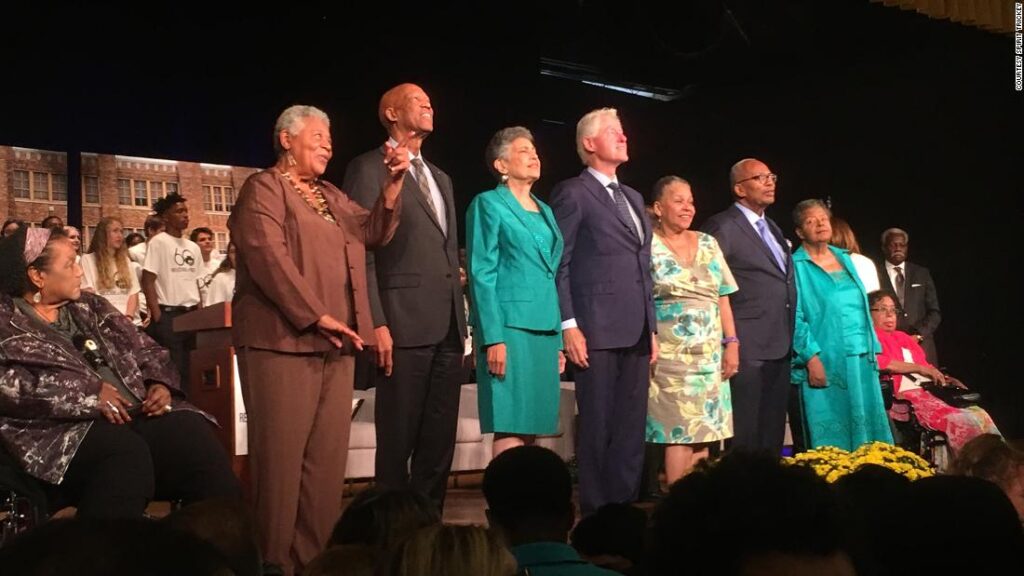

Courtesy Spirit Trickey

Surviving members of the Little Rock Nine stand with former President Bill Clinton at Little Rock Central High School for the 60th anniversary of the school’s desegregation in 2017. Left to right: Melba Pattillo Beals, Minnijean Brown-Trickey, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Clinton, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, and Thelma Mothershed-Wair.