Fannie Lou Hamer: Civil Rights Activist

Hamer lifts banner at the 1964 National Democratic Convention. Photograph by Fred DeVan. Photograph courtesy The Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Fannie Lou Hamer, seated at left, at a meeting of the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union, a union of black domestic workers and day laborers. Photograph courtesy The Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

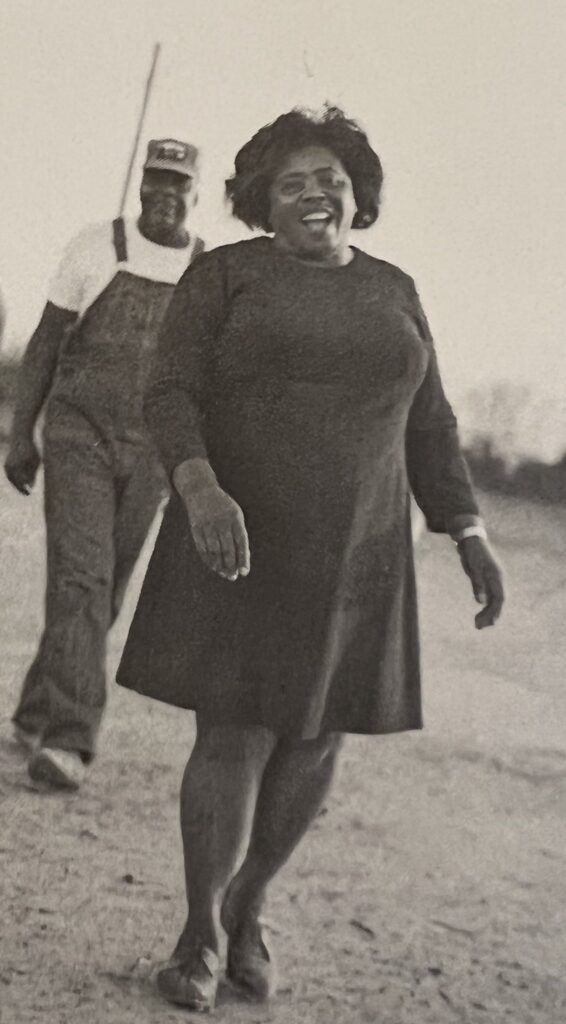

Hamer, in coat and scarf, helped establish Freedom Farm Cooperative in 1969 with the goal to provide food and some economic independence to local people. Photograph courtesy The Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Tougaloo College presents Hamer with a Doctor of Humanities honorary degree in 1969. Photograph courtesy The Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Hamer speaks on Tougaloo College campus, June 1971. Photograph courtesy The Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Election poster for Hamer’s 1971 run for the Mississippi Senate. Courtesy The Tougaloo College Civil Rights Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

https://mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/fannie-lou-hamer-civil-rights-activist

Fannie Lou Hamer and future Congressman John Lewis came to Cleveland to honor Civil Rights martyr Rev. Bruce Klunder, who was killed during a C.O.R.E. protest at the construction site of Stephen E. Howe Elementary School in 1965.

BOOKS

Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America (2021)

National Book Critics Circle 2021 Biography Finalist

53rd NAACP Image Award Nominee: Outstanding Literary Work – Biography/Autobiography

“[A] riveting and timely exploration of Hamer’s life. . . . Brilliantly constructed to be both forward and backward-looking, Blain’s book functions simultaneously as a much-needed history lesson and an indispensable guide for modern activists.”—New York Times Book Review

Ms. Magazine “Most Anticipated Reads for the Rest of Us – 2021” · KIRKUS STARRED REVIEW · BOOKLIST STARRED REVIEW · Publishers Weekly Big Indie Books of Fall 2021

Explores the Black activist’s ideas and political strategies, highlighting their relevance for tackling modern social issues including voter suppression, police violence, and economic inequality.

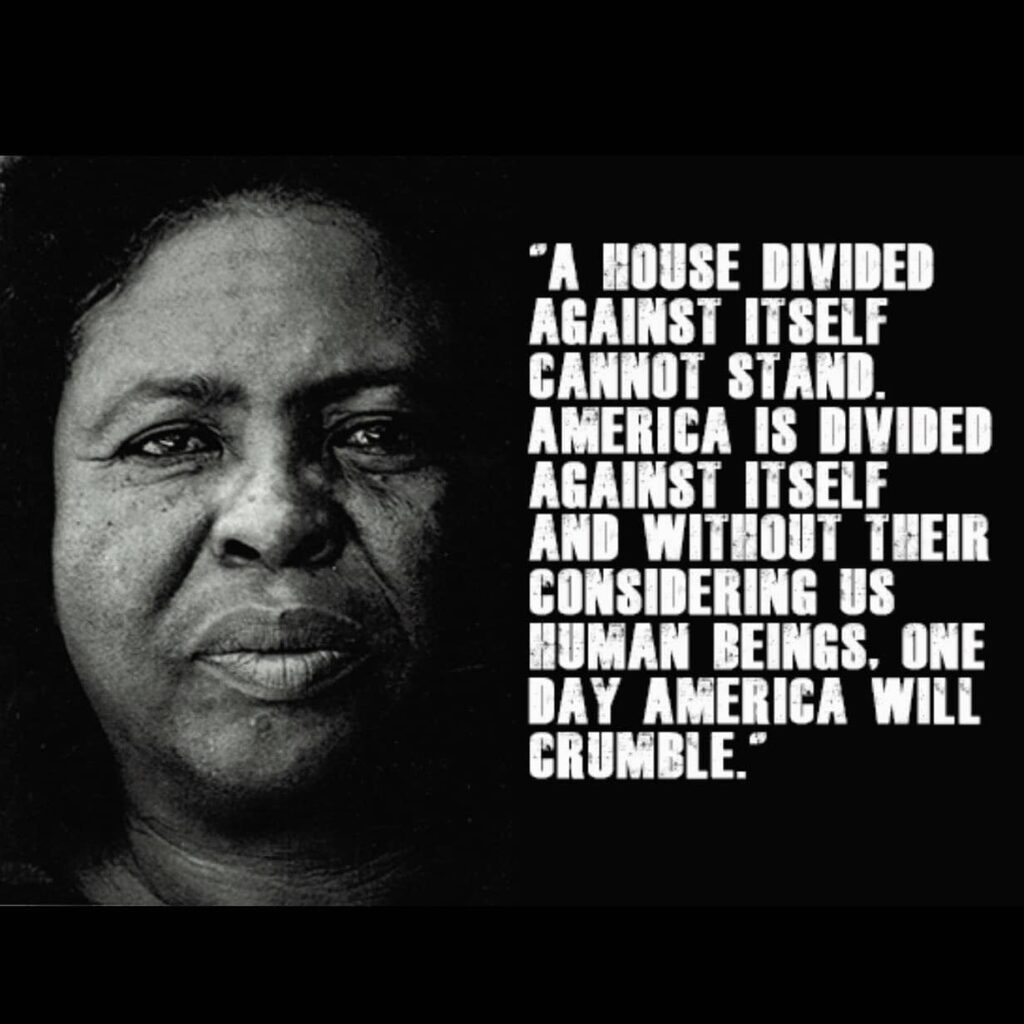

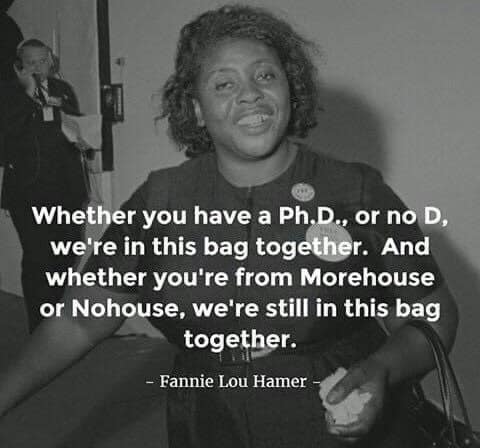

“We have a long fight and this fight is not mine alone, but you are not free whether you are White or Black until I am free.”

—Fannie Lou Hamer

A blend of social commentary, biography, and intellectual history, Until I Am Free is a manifesto for anyone committed to social justice. The book challenges us to listen to a working-poor and disabled Black woman activist and intellectual of the civil rights movement as we grapple with contemporary concerns around race, inequality, and social justice.

Award-winning historian and New York Times best-selling author Keisha N. Blain situates Fannie Lou Hamer as a key political thinker alongside leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Rosa Parks and demonstrates how her ideas remain salient for a new generation of activists committed to dismantling systems of oppression in the United States and across the globe.

Despite her limited material resources and the myriad challenges she endured as a Black woman living in poverty in Mississippi, Hamer committed herself to make a difference in the lives of others. She refused to be sidelined in the movement and refused to be intimidated by those of higher social status and with better jobs and education. In these pages, Hamer’s words and ideas take center stage, allowing us all to hear the activist’s voice and deeply engage her words, as though we had the privilege to sit right beside her.

More than 40 years since Hamer’s death in 1977, her words still speak truth to power, laying bare the faults in American society and offering valuable insights on how we might yet continue the fight to help the nation live up to its core ideals of “equality and justice for all.”

Includes a photo insert featuring Hamer at civil rights marches, participating in the Democratic National Convention, testifying before Congress, and more.

*

Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer Hardcover – (2021)

She was born the 20th child in a family that had lived in the Mississippi Delta for generations, first as enslaved people and then as sharecroppers. She left school at 12 to pick cotton, as those before she had done, in a world in which white supremacy was an unassailable citadel. She was subjected without her consent to an operation that deprived her of children. And she was denied the most basic of all rights in America―the right to cast a ballot―in a state in which Blacks constituted nearly half the population.

And so Fannie Lou Hamer lifted up her voice. Starting in the early 1960s and until her death in 1977, she was an irresistible force, not merely joining the swelling wave of change brought by civil rights but keeping it in motion. Working with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which recruited her to help with voter registration drives, Hamer became a community organizer, women’s rights activist, and co-founder of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. She summoned and used what she had against the citadel―her anger, her courage, her faith in the Bible, and her conviction that hearts could be won over and injustice overcome. She used her brutal beating at the hands of Mississippi police, an ordeal from which she never fully recovered, as the basis of a televised speech at the 1964 Democratic Convention, a speech that the mainstream party―including its standard-bearer, President Lyndon Johnson―tried to contain. But Fannie Lou Hamer would not be held back. For those whose lives she touched and transformed, for those who heard and followed her voice, she was the embodiment of protest, perseverance, and, most of all, the potential for revolutionary change.

Kate Clifford Larson’s biography of Fannie Lou Hamer is the most complete ever written, drawing on recently declassified sources on both Hamer and the civil rights movement, including unredacted FBI and Department of Justice files. It also makes full use of interviews with Civil Rights activists conducted by the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress, and Democratic National Committee archives, in addition to extensive conversations with Hamer’s family and with those with whom she worked most closely. Stirring, immersive, and authoritative, Walk with Me does justice to Fannie Lou Hamer’s life, capturing in full the spirit, and the voice, that led the fight for freedom and equality in America at its critical moment.

*

Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer: The Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement Paperback – Illustrated, (2018)

2016 Robert F. Sibert Honor Book

2016 John Steptoe New Talent Illustrator Award Winner

Stirring poems and stunning collage illustrations combine to celebrate the life of Fannie Lou Hamer, a champion of equal voting rights.“I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.”Despite fierce prejudice and abuse, even being beaten to within an inch of her life, Fannie Lou Hamer was a champion of civil rights from the 1950s until her death in 1977. Integral to the Freedom Summer of 1964, Ms. Hamer gave a speech at the Democratic National Convention that, despite President Johnson’s interference, aired on national TV news and spurred the nation to support the Freedom Democrats. Featuring vibrant mixed-media art full of intricate detail, Voice of Freedom celebrates Fannie Lou Hamer’s life and legacy with a message of hope, determination, and strength.

The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell It Like It Is (Margaret Walker Alexander Series in African American Studies) (2013)

Most people who have heard of Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977) are aware of the impassioned testimony that this Mississippi sharecropper and civil rights activist delivered at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Far fewer people are familiar with the speeches Hamer delivered at the 1968 and 1972 conventions, to say nothing of addresses she gave closer to home, or with Malcolm X in Harlem, or even at the founding of the National Women’s Political Caucus. Until now, dozens of Hamer’s speeches have been buried in archival collections and in the basements of movement veterans. After years of combing library archives, government documents, and private collections across the country, Maegan Parker Brooks and Davis W. Houck have selected twenty-one of Hamer’s most important speeches and testimonies.

As the first volume to exclusively showcase Hamer’s talents as an orator, this book includes speeches from the better part of her fifteen-year activist career delivered in response to occasions as distinct as a Vietnam War Moratorium Rally in Berkeley, California, and a summons to testify in a Mississippi courtroom.

Brooks and Houck have coupled these heretofore unpublished speeches and testimonies with brief critical descriptions that place Hamer’s words in context. The editors also include the last full-length oral history interview Hamer granted, a recent oral history interview Brooks conducted with Hamer’s daughter, as well as a bibliography of additional primary and secondary sources. The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer demonstrate that there is still much to learn about and from this valiant black freedom movement activist.

*

This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer (Civil Rights and the Struggle for Black Equality in the Twentieth Century) – Illustrated (2007)

*

Fannie Lou Hamer: The Life of a Civil Rights Icon

This book explores the life of one of Mississippi’s greatest civil rights activists, Fannie Lou Hamer. Known for her daring, brinkmanship, and her impassioned speech-making, Hamer rose to prominence in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, an intrepid group that tried to unseat the predominantly white Democrats of Mississippi during the 1964 Democratic National Convention. She is particularly remembered for her speech before the Credentials Committee, seeking to end all-White representation of her home state. Hamer fought her entire life to expand freedom and basic rights to African Americans in the United States.

*

A Voice That Could Stir an Army: Fannie Lou Hamer and the Rhetoric of the Black Freedom Movement (Race, Rhetoric, and Media Series) Paperback – February 12, 2016

A sharecropper, a warrior, and a truth-telling prophet, Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977) stand as a powerful symbol not only of the 1960s black freedom movement but also of the enduring human struggle against oppression. A Voice That Could Stir an Army is a rhetorical biography that tells the story of Hamer’s life by focusing on how she employed symbols―images, words, and even material objects such as the ballot, food, and clothing―to construct persuasive public personae, to influence audiences, and to effect social change.

Drawing upon dozens of newly recovered Hamer texts and recent interviews with Hamer’s friends, family, and fellow activists, Maegan Parker Brooks moves chronologically through Hamer’s life. Brooks recounts Hamer’s early influences, her intersection with the Black freedom movement, and her rise to prominence at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Brooks also considers Hamer’s lesser-known contributions to the fight against poverty and to feminist politics before analyzing how Hamer is remembered posthumously. The book concludes by emphasizing what remains rhetorical about Hamer’s biography, using the 2012 statue and museum dedication in Hamer’s hometown of Ruleville, Mississippi, to examine the larger social, political, and historiographical implications of her legacy.

The sustained consideration of Hamer’s wide-ranging use of symbols and the reconstruction of her legacy provided within the pages of A Voice That Could Stir an Army enriches the understanding of this key historical figure. This book also demonstrates how rhetorical analysis complements historical reconstruction to explain the dynamics of how social movements actually operate.

Music, particularly hymns, in Fannie Lou Hamer’s activism

. Her powerful singing calmed and inspired fellow activists, sustained morale during terrifying situations, and articulated the spiritual foundation of the civil rights struggle.

- Calmed fear: It helped people endure intimidation and find a sense of inner peace. Activist Worth Long recounted that Hamer sang “songs of salvation, songs of redemption, songs of struggle… and it calmed the people as they sat there on the bus”.

- Unified the group: The communal act of singing helped bind individuals together, creating a sense of solidarity and shared purpose.

- Kept hope alive: Like enslaved people who sang spirituals to cope with suffering, Hamer’s songs added “hope to our determination,” according to Martin Luther King, Jr., a sentiment Hamer shared.

- “This Little Light of Mine”: One of Hamer’s most iconic songs, she transformed it from a simple hymn into a powerful anthem for Black political power. Singing “all in the jailhouse, I’m going to let it shine,” she subverted its religious meaning into a bold, defiant political statement.

-

This Little Light of Mine

-

- Theology of struggle: Hamer often referenced her beliefs in her songs and speeches, grounding the struggle for justice in a divine mandate. Her singing fused her deep religious conviction with her demand for equality, framing the civil rights movement not just as a political effort, but as a righteous cause.

- Undermined the opposition: As songs of freedom and faith, hymns helped counter the violent tactics and accusations of opponents. The familiar nature of the music made it difficult for critics to portray the movement as a radical or foreign threat.

Walk With Me

This is an image for the TV show “Fannie Lou Hamer’s America: An America ReFramed Special,” – Feb. 22, 2022, on PBS. In this photo, Hamer, a member of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, enters the 1964 National Democratic Convention in Atlantic City, N.J. (CNS photo/Bettmann, courtesy PBS)

Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker Intelligence Countered, (2019)

Justin Brown (Artist)

“In 1964, working with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Hamer helped organize the 1964 Freedom Summer African American voter registration drive in her native Mississippi.“

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

“The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was founded in 1960 in the wake of student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters across the South and became the major channel of student participation in the civil rights movement. Members of SNCC included prominent future leaders such as former Washington, D.C. Mayor Marion Barry, Congressman John Lewis, and NAACP chairman Julian Bond.

SNCC Emerges From the Sit-In Movement

In February 1960, four Black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, stayed in their seats at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter after the staff refused to serve them. Some 300 students soon joined their protest, which received widespread media coverage, sparking a movement of similar sit-ins by thousands of students at segregated establishments across the South.

Civil rights leaders recognized such young activists as a powerful new force in their efforts to combat racial discrimination and win equal rights for Black Americans. As the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. acknowledged in a speech at a North Carolina church in mid-February 1960: “What is new in your fight is the fact that it was initiated, fed, and sustained by students.”

Seeking to harness the momentum of the sit-in movement, veteran civil rights organizer Ella Baker invited students who had taken part in the sit-ins to a gathering at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina in April 1960. Baker had begun her career of activism as a student at Shaw more than 40 years earlier. She worked for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the 1940s and helped King organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) after the Montgomery Bus Boycott. At the time of the sit-ins, she was the SCLC’s executive director.

Founding of SNCC and the Freedom Rides

Some 200 students attended the conference at Shaw University from April 16-18, 1960, during which the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) was born. Though King and others hoped that SNCC would function as the youth wing of the SCLC, Baker stressed the importance of remaining independent and unaffiliated with other civil rights groups.

Beginning its operations in a corner of the SCLC’s Atlanta office, SNCC dedicated itself to organizing sit-ins, boycotts, and other nonviolent direct-action protests against segregation and other forms of racial discrimination. In April 1961, SNCC activists joined a campaign launched by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), another civil rights group, to desegregate interstate bus transportation. Although the Supreme Court had ruled it was unconstitutional, bus travel continued to be segregated across the South.”

During the Freedom Rides in May 1961, teams of activists (many of them students) rode buses in mixed racial groups into and across the South. Diane Nash, one of the few prominent women in the sit-in movement and a founding member of SNCC, helped organize the protest and recruit riders. The freedom riders met with violent resistance on the part of local law enforcement and white segregationist Southerners; hundreds of them were arrested, beaten, and threatened with death. That November, the Interstate Commerce Commission finally mandated the full desegregation of all interstate travel facilities, giving SNCC its first solid victory on a national level.

Freedom Summer

Building on its focus on direct action (sit-ins, protests, boycotts) SNCC began working to combat one of the most difficult issues of the civil rights movement: the disenfranchisement of Black voters across the South through discriminatory voting laws, intimidation, and violence. Starting in late 1961, SNCC organizers began embedding themselves in rural communities and recruiting local young people to join in voter registration efforts.

In 1964, SNCC and other civil rights groups decided to focus their grassroots voting rights campaign on Mississippi. During Freedom Summer, hundreds of volunteers poured into Mississippi, joining efforts to increase Black voter registration and establish “Freedom Schools” for Black children throughout the state.

Segregationists in Mississippi, including both local law enforcement and white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, met the influx of volunteers with a solid wall of resistance. By the end of the summer, they had arrested hundreds of volunteers, beaten dozens and brutally murdered at least three—Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, white men from New York, and James Chaney, a local Black man.

Shift from Nonviolence to Black Power

SNCC members were outraged by events at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, where the party refused to replace the all-white Mississippi delegation with one from the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Their anger contributed to a growing distance between SNCC and more mainstream civil rights organizations like King’s SCLC.

This divide continued after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as some within the group began advocating for a Black-only political party in Mississippi and other more radical steps beyond nonviolent direct action. These included Stokely Carmichael, who became chairman of SNCC in 1966, replacing John Lewis. Carmichael’s use of the phrase “Black Power” during the March Against Fear, a voting rights march in Mississippi that June marked SNCC’s transition to a focus on Black self-reliance and the plight of low-income Black people living in urban centers.

Hurbert “Rap” Brown, who succeeded Carmichael in 1967, went even further down this path, forging a public alliance with the Black Panther Party. In 1968, Brown replaced “Nonviolent” in SNCC’s name with “National.” With white activists increasingly leaving the group, its income declined, forcing a reduction in direct action organizing efforts. By 1970, with the civil rights movement itself splintering into factions, SNCC had lost its employees and most of its branches. With Brown facing various legal charges, the organization struggled to survive, and by the end of 1973 SNCC no longer existed.

Sources

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University.

“The Story of SNCC.” Digital SNCC Gateway.

“The SNCC Project: A Year by Year History, 1960-70.” Mapping American Social Movements Project, University of Washington.

~TIMELINE~

October 6, 1917, – Fannie Lou Townsend was born the twentieth child of James Lee and Lou Ella Townsend in Montgomery County, Mississippi.

1919 –In search of work, the Townsend family moved to E.W. Brandon’s plantation in Sunflower, County Mississippi.

1930 – Fannie Lou left school so she could help her family financially by working full-time in the fields.

1944 – Fannie Lou Townsend marries Perry Hamer and moves to the W.D. Marlow plantation, four miles outside the city of Ruleville, Mississippi.

1944-1961 – Fannie Lou and Perry Hamer adopt two children from their community, Dorothy Jean and Vergie Ree. They also care for Lou Ella Townsend, Fannie Lou’s disabled mother, while working on W.D. Marlow’s plantation.

August 27, 1962, – Fannie Lou and Perry Hamer attend a mass meeting at William’s Chapel Missionary Baptist Church. There they learn from civil rights activists that African American people have a constitutionally- guaranteed right to vote.

August 31, 1962, – Fannie Lou Hamer attempts to register to vote at the Sunflower County Courthouse in Indianola, Mississippi. She

fails the registration test. As punishment for her attempt, she is fired and evicted from the Marlow plantation upon her return home.

Fall-Winter of 1962 – Fannie Lou Hamer becomes the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee’s (SNCC) oldest voter registration worker. She attends workshops across the South to learn how to encourage people in her community to become politically active.

January 1963 – Passes the voter registration test on her second try and becomes among the first registered black voters in Ruleville, Mississippi.

June 1963 – Arrested in Winona, Mississippi on her return trip from a voter education workshop. She and several other civil rights activists with whom she is jailed are beaten while in police custody.

Spring of 1964 – Becomes the first Black woman to run for US Congress and the first Black person to run from her district since the 19th Century.

August 22, 1964, – On behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Hamer testified

at the Democratic National Convention about the harassment and abuse she experienced in Mississippi for trying to vote. Her testimony is broadcast nationally.

September-October 1964 – Travels to the West Coast of Africa, with other members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, as an honored guest of the Guinean government.

December 1964 – Speaks to crowds in Harlem, New York alongside the Black Nationalist Leader, Malcolm X.

January 4, 1965, – On behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Hamer, Annie Devine, and Victoria Gray challenge the

seating of the five US congressmen sent from Mississippi. They argue that since black people are unconstitutionally prohibited from voting in Mississippi, the representatives do not actually represent the state and, therefore, shouldn’t be allowed to serve in the United States Congress.

April 23, 1965, – Becomes the lead plaintiff in the lawsuitHamer v. Campbell, suggesting that elections in Sunflower County should be suspended until black people are given a fair chance to register.

June 1966 – Marched alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. and spoke to protestors along the Meredith March Against Fear in Mississippi.

Spring 1967 – Fannie Lou Hamer’s eldest daughter, Dorothy Jean, dies from complications related to anemia, malnutrition, and inadequate access to health care. Fannie Lou and Pap Hamer adopt Dorothy Jean’s two daughters, Jacqueline and Lenora.

August 20, 1968, – Formally seated as a delegate from Mississippi to the Democratic National Convention, Hamer receives a standing ovation from the convention floor for her tireless advocacy of voting rights.

1968 – With the help of the National Council of Negro Women, Hamer starts a “Pig Bank” in Sunflower County to provide protein to malnourished members of her community.

1968-1972 – Fannie Lou Hamer receives honorary doctorates from numerous universities, including Columbia College and Tougaloo College. She also was named the “First Lady of Civil Rights,” by the League of Black Women and she received the “Noble Example of Womanhood” and the Mary Church Terrell Awards during this period.

1969 – With the money she raised by speaking to audiences across the country, Hamer buys the first 40 acres of “Freedom Farm,” a cooperative established to provide food and jobs for people in her community. Freedom Farm eventually grew to nearly 700 acres and became the third largest employer in Sunflower County.

July 10, 1971, – Spoke at, and participated as a founding member of, the National Women’s Political Caucus in Washington, D.C.

July 13, 1972, – Hamer is an official delegate from Mississippi to the Democratic National Convention, where she offers a speech in support of Frances Farenthold’s candidacy for Vice President.

1972-1976 – Helps secure affordable housing for people in Ruleville, while traveling nationally to raise funds for Freedom Farm and advocating for prison and poverty program reforms in Mississippi.

1976-1977 – Battles breast cancer, hypertension, and diabetes.

March 14, 1977, – Dies of heart failure at a hospital in Mound Bayou, Mississippi.

FANNIE LOU HAMER (left). ELLA BAKER (right). STOKELY CARMICHAEL

Examples of Her Legacy

July 27, 2004, – The Democratic National Convention honors Fannie Lou Hamer on the 40th Anniversary of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s Credentials Committee Challenge.

2006 – The United States Congress reauthorizes the 1965 Voting Rights Act and names it after Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Coretta Scott King.

February 17, 2009, – The International Slavery Museum recognizes Hamer as a “Black Achiever” and hangs her portrait next to one of President Barack Obama in their permanent exhibit.

February 21, 2009, – The US Postal Service included Fannie Lou Hamer among twelve

civil rights pioneers were honored on postage stamps in recognition of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People’s 100th Anniversary.

October 6, 2012, – In her hometown of Ruleville, Mississippi, an eight-foot bronze statue of Fannie Lou Hamer is dedicated on what would have been her 95th Birthday.

August 8, 2015, – Black Lives Matter protestors in Seattle, Washington interrupt Presidential Candidate Bernie Sanders’ political rally. The protestor who speaks to the crowd about Black Lives Matter’s concerns dons a “Fight Like Fannie Lou” t-shirt.

August 2018 – Shelby County, Tennessee Commissioner, Tami Sawyer, is sworn into office on a biography about Fannie Lou Hamer and a collection of her speeches.

Summer 2019 – The feature film,Fannie Lou Hamer’s Americaand the K-12 Find Your Voice curriculum is released on the Find Your Voice: Online Resources for Fannie Lou Hamer Studies website:www.findyourvoice.willamette.edu

Civil rights activism

Early activism

On August 23, 1962, Rev. James Bevel, an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and an associate of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave a sermon in Ruleville, Mississippi, and followed it with an appeal to those assembled to register to vote. Black people who registered to vote in the South faced serious hardships at that time due to institutionalized racism, including harassment, loss of their jobs, beatings, and lynchings; nonetheless, Hamer was the first volunteer. She later said, “I guess if I’d had any sense, I’d have been a little scared — but what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do was kill me, and it kinda seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time since I could remember.”

On August 31, she traveled on a rented bus with other attendees of Bevel’s sermon to Indianola, Mississippi, to register. In what would become a signature trait of Hamer’s activist career, she began singing Christian hymns, such as “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and “This Little Light of Mine”, to the group in order to bolster their resolve. The hymns also reflected Hamer’s belief that the civil rights struggle was a deeply spiritual one. That same day, upon Hamer’s return to her plantation, she was fired by Marlow who told her not to try to vote.

Hamer’s courage and leadership in Indianola came to the attention of SNCC organizer Bob Moses, who dispatched Charles McLaurin from the organization with instructions to find “the lady who sings the hymns”. McLaurin found and recruited Hamer, and though she remained based in Mississippi, she began traveling around the South doing activist work for the organization.

On June 9, 1963, Hamer was on her way back from Charleston, South Carolina with other activists from a literacy workshop. Stopping in Winona, Mississippi, the group was arrested on a false charge and jailed. Once in jail, Hamer’s colleagues were beaten by the police in the booking room. Hamer was then taken to a cell where two inmates were ordered, by the police, to beat her using a blackjack. The police ensured she was held down during the almost fatal beating and beat her further when she started to scream.

Released on June 12, she needed more than a month to recover. Though the incident had profound physical and psychological effects, Hamer returned to Mississippi to organize voter registration drives, including the “Freedom Ballot Campaign”, a mock election, in 1963, and the “Freedom Summer” initiative in 1964. She was known to the volunteers of Freedom Summer — most of whom were young, White, and from northern states — as a motherly figure who believed that the civil rights effort should be multi-racial in nature. In addition to her “Northern” guests, Hamer played host to Tuskegee University student activists Sammy Younge Jr. and Wendell Paris. Younge and Paris grew to become profound activists and organizers under Hamer’s tutelage. (Younge ultimately gave his life for the movement in 1966, when he was murdered at a Standard Oil gas station in Macon County, Alabama for using a “whites-only” bathroom.)

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

In the summer of 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, or “Freedom Democrats” for short, was organized with the purpose of challenging Mississippi’s all-white and anti-civil rights delegation to the Democratic National Convention, which failed to represent all Mississippians. Hamer was elected Vice-Chair.

The Freedom Democrats’ efforts drew national attention to the plight of African Americans in Mississippi, and represented a challenge to President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was seeking the Democratic Party’s nomination for reelection; their success would mean that other Southern delegations, who were already leaning toward Republican challenger Barry Goldwater, would publicly break from the convention’s decision to nominate Johnson — meaning in turn that he would almost certainly lose those states’ electoral votes. Hamer, singing her signature hymns, drew a great deal of attention from the media, enraging Johnson, who referred to her in speaking to his advisors as “that illiterate woman”.

Hamer was invited, along with the rest of the MFDP officers, to address the Convention’s Credentials Committee. She recounted the problems she had encountered in registration, and the ordeal of the jail in Winona. Near tears, she concluded:

In Washington, D.C., President Johnson, fearful of the power of Hamer’s testimony on live television, called an emergency press conference in an effort to divert press coverage. The television networks switched to the White House from their coverage of Hamer’s address, believing that Johnson would announce his vice-presidential candidate for the forthcoming November election. Instead, to the bemusement of journalists, he arbitrarily announced the nine-month anniversary of the shooting of Texas governor, John Connally, during the assassination of John F. Kennedy. However, many television networks ran Hamer’s speech unedited on their late news programs. The Credentials Committee received thousands of calls and letters in support of the Freedom Democrats.

Johnson then dispatched several trusted Democratic Party operatives to attempt to negotiate with the Freedom Democrats, including Senator Hubert Humphrey (who was campaigning for the Vice-Presidential nomination), Walter Mondale, and Walter Reuther, as well as J. Edgar Hoover. They suggested a compromise that would give the MFDP two non-voting seats in exchange for other concessions and secured the endorsement of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for the plan. But when Humphrey outlined the compromise, saying that his position on the ticket was at stake, Hamer, invoking her Christian beliefs, sharply rebuked him:

Future negotiations were conducted without Hamer, and the compromise was modified such that the Convention would select the two delegates to be seated “at large”, with no voting rights. The MFDP rejected the compromise, with Hamer making the famous quote:

In 1968 the MFDP was finally seated after the Democratic Party adopted a clause that demanded equality of representation from their states’ delegations. In 1972, Hamer was elected as a national party delegate.

Political activism and philanthropy

In 1964 and 1965 Hamer ran for Congress but failed to win. Hamer continued to work on other projects, including grassroots-level Head Start programs, the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County, and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign.

- Challenging segregation: Hamer was a driving force behind the MFDP, a courageous effort to challenge the all-white, segregationist Mississippi Democratic Party in 1964.

- National recognition: Hamer’s moving testimony at the 1964 Democratic National Convention brought the MFDP’s efforts and the struggles faced by Black people in the South to national prominence.

- Grassroots mobilization: Hamer played a crucial role in organizing Freedom Summer in 1964, which brought hundreds of college students, both Black and white, to Mississippi to assist with African American voter registration and education in the face of intense segregation.

- Freedom Farm Cooperative (FFC): Recognizing the link between racial and economic justice, Hamer launched the FFC in 1969 to address the economic hardships faced by African Americans in the Mississippi Delta.

- Providing opportunities: The FFC provided land ownership, employment, and various support services like financial counseling and housing assistance, says the National Women\’s History Museum.

- Addressing poverty and food insecurity: She also started a “pig bank” to provide free pigs for Black farmers and initiated programs to address malnutrition in her community.

- National Women’s Political Caucus: Hamer co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971, advocating for women’s rights and their full inclusion in the political sphere, according to the National Women\’s History Museum.

- Building solidarity: She stressed the importance of unity among women, famously stating, “A white mother is no different from a black mother. The only thing is they haven’t had as many problems. But we cry the same tears”.

- Head Start programs: Hamer started a child care center and brought the Head Start program to rural Mississippi to address the needs of children of working mothers.

- Housing initiatives: She helped build low-income housing units through Young World Developers.

Fannie Lou Hamer

Jerry Lynn (Artist)

“On June 9, 1963, while returning from a voter registration workshop in South Carolina, Fannie Lou Hamer and other civil rights activists were arrested in Winona, Mississippi. Ms. Hamer and the other activists had been traveling in the “White” section of a Greyhound bus despite threats from the driver that he planned to notify local police at the next stop. When the bus arrived at the Winona bus depot, the activists sat at the “white only” lunch counter inside the terminal. Winona Police Chief Thomas Herrod ordered the group to go to the “Colored” side of the depot and arrested them when one of the activists tried to write down his patrol car license number.

At the county jail, White jailers forced two African American prisoners to savagely beat Ms. Hamer with loaded Blackjacks and she was nearly killed. As she regained consciousness, she overheard one of the White officers propose, “We could put them SOBs in [the] Big Black [River] and nobody would ever find them.”

Ms. Hamer never fully recovered from the attack; she lost vision in one of her eyes and suffered permanent kidney damage, which contributed to her death in 1977 at age 59. Lawyers with the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee filed suit against the Winona police who brutalized the activists but an all-White jury acquitted them. Despite the trauma she experienced, Ms. Hamer returned to Mississippi to continue organizing voter registration drives and remained active in civil rights causes until her death.

Ms. Hamer never fully recovered from the attack; she lost vision in one of her eyes and suffered permanent kidney damage.” – © Equal Justice Initiative 2025

Legacy

Compositions based on Hamer’s life

- Sweet Honey in the Rock, the Washington DC-based African American female a cappella singing group, wrote and recorded a song called “Fannie Lou Hamer.”

- Dark River, an opera about Hamer written by composer and pianist Mary D. Watkins, premiered in November 2009 in Oakland, California.

- “All of the Places We’ve Been” by Gil Scott-Heron with Brian Jackson.

- On Oct. 6, 2012 (the 95th anniversary of Mrs. Hamer’s birth), a musical written by Felicia Hunter — titled “Fannie Lou” — was premiered in New York City.

William Parker – For Those Who Are, Still (2015)CD 1 – For Fannie Lou Hamer Label: AUM Fidelity Recorded at The Gallery Recording Studio, Brooklyn on March 6, 2011.

Other tributes

- There is a Fannie Lou Hamer Memorial Garden in Ruleville, Mississippi. It was rededicated by the city on July 12, 2008. The Fannie Lou Hamer Civil Rights Marker (part of the Memorial Garden) was unveiled on May 25, 2011. A statue of Fannie Lou Hamer was unveiled in October 2012 at the Memorial Garden.

- In 1970 Ruleville Central High School held a “Fannie Lou Hamer Day”.

- In 1976 the City of Ruleville celebrated a “Fannie Lou Hamer Day”.

- On June 30, 2015, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings released the album “Songs My Mother Taught Me by Fannie Lou Hamer.”

Fannie Lou Hamer by artist Ingrid Yuzly Mathurin, titled “Tired,” [references Hamer’s famous refrain, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.”]

Honors and awards

- Honorary Degree of Doctor of Humanities from Tougaloo College and Shaw University. She also received honorary degrees from Columbia College Chicago (1970). and Howard University (1972)

- Recipient of the National Sojourner Truth Meritorious Service Award.

- Recipient of the Paul Robeson Award from Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority.

- Recipient of the Mary Church Terrell Award and Honorary lifetime member from Delta Sigma Theta.

- Inductee of the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

[Wikipedia]

“She brought the civil rights struggle in Mississippi to the attention of the entire nation during a televised session at the convention. The next year, Hamer ran for Congress in Mississippi, but she was unsuccessful in her bid. Along with her political activism, Hamer worked to help the poor and families in need in her Mississippi community. She also set up organizations to increase business opportunities for minorities and to provide childcare and other family services.”

LINKS

https://www.fannielouhamersamerica.com

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/fannie-lou-hamer

https://www.wjtv.com/news/marker-will-honor-civil-rights-activist-fannie-lou-hamer/

https://www.fannielouhamersamerica.com/fannie-lou-hamer-resource-center/loss-of-an-icon?fbclid=IwAR3Sa6x016zUv73iTQNPuqs12wP0h3OhGZSHQh4JDqslF7Le4TNh_KHu8h4

https://eji.org/news/remembering-1963-fannie-lou-hamer-arrested-and-beaten-winona-mississippi/?fbclid=IwY2xjawMNGJRleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHqKIJf53KXo4RbYCZwwARfArWQKdfioSUPrMbBfpgMPcCI51OCC7kOCxeMRz_aem_OVC1jDyMwTOethx5UkjA-A

BHM100*: Remembering Fannie Lou Hamer, the Mississippi Plantation Worker Jailed and Beaten for Trying to Vote; She Fought Back as a Civil Rights Activist, Organizer and Powerful Speaker

|

PHOTOGRAPHY Credits

ALAMY.com

ASSOCIATED PRESS (AP)

© Bettmann/Corbis

BIOGRAPHY.COM

Corbis via Getty Images

Ebony Magazine

Flickr

Getty Images

Jet Magazine

New York Times -nytimes.org

PBS.org

Pinterest.com

Shutterstock

Smithsonian Magazine

Tumblr

Wikimedia Commons

Iforcolor.org – NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED 2025 – DRS

EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY

Fannie Lou Hamer (photo via PICRYL Creative Commons)

Fannie Lou Hamer (photo via PICRYL Creative Commons)