Fannie Lou Hamer

Civil rights activism

Early activism

On August 23, 1962, Rev. James Bevel, an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and an associate of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave a sermon in Ruleville, Mississippi, and followed it with an appeal to those assembled to register to vote. Black people who registered to vote in the South faced serious hardships at that time due to institutionalized racism, including harassment, loss of their jobs, beatings, and lynchings; nonetheless, Hamer was the first volunteer. She later said, “I guess if I’d had any sense, I’d have been a little scared — but what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do was kill me, and it kinda seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time since I could remember.”

On August 31, she traveled on a rented bus with other attendees of Bevel’s sermon to Indianola, Mississippi, to register. In what would become a signature trait of Hamer’s activist career, she began singing Christian hymns, such as “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and “This Little Light of Mine”, to the group in order to bolster their resolve. The hymns also reflected Hamer’s belief that the civil rights struggle was a deeply spiritual one. That same day, upon Hamer’s return to her plantation, she was fired by Marlow who told her not to try to vote.

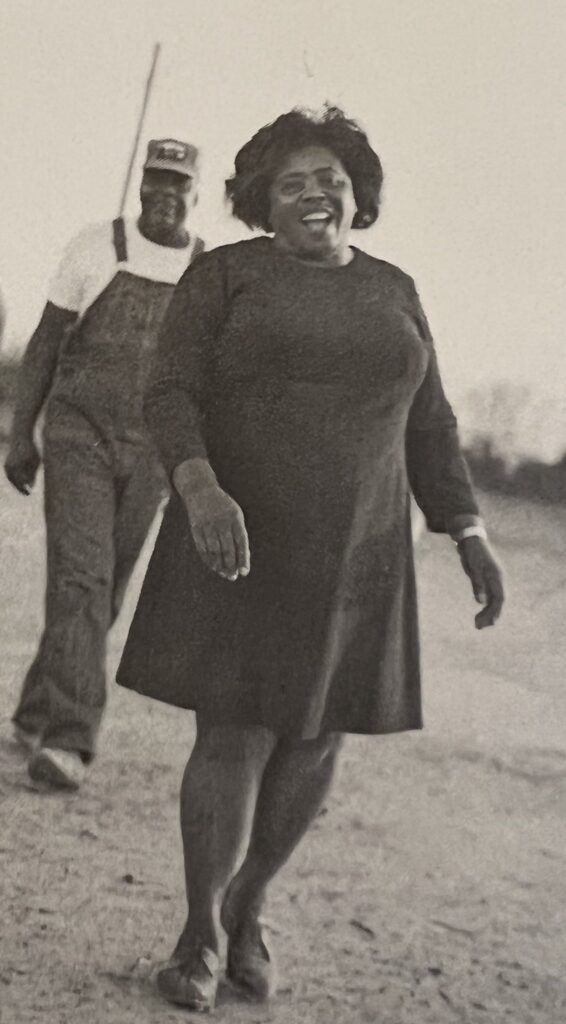

Hamer’s courage and leadership in Indianola came to the attention of SNCC organizer Bob Moses, who dispatched Charles McLaurin from the organization with instructions to find “the lady who sings the hymns”. McLaurin found and recruited Hamer, and though she remained based in Mississippi, she began traveling around the South doing activist work for the organization.

On June 9, 1963, Hamer was on her way back from Charleston, South Carolina with other activists from a literacy workshop. Stopping in Winona, Mississippi, the group was arrested on a false charge and jailed. Once in jail, Hamer’s colleagues were beaten by the police in the booking room. Hamer was then taken to a cell where two inmates were ordered, by the police, to beat her using a blackjack. The police ensured she was held down during the almost fatal beating and beat her further when she started to scream.

Released on June 12, she needed more than a month to recover. Though the incident had profound physical and psychological effects, Hamer returned to Mississippi to organize voter registration drives, including the “Freedom Ballot Campaign”, a mock election, in 1963, and the “Freedom Summer” initiative in 1964. She was known to the volunteers of Freedom Summer — most of whom were young, White, and from northern states — as a motherly figure who believed that the civil rights effort should be multi-racial in nature. In addition to her “Northern” guests, Hamer played host to Tuskegee University student activists Sammy Younge Jr. and Wendell Paris. Younge and Paris grew to become profound activists and organizers under Hamer’s tutelage. (Younge ultimately gave his life for the movement in 1966, when he was murdered at a Standard Oil gas station in Macon County, Alabama for using a “whites-only” bathroom.)

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

In the summer of 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, or “Freedom Democrats” for short, was organized with the purpose of challenging Mississippi’s all-white and anti-civil rights delegation to the Democratic National Convention, which failed to represent all Mississippians. Hamer was elected Vice-Chair.

The Freedom Democrats’ efforts drew national attention to the plight of African Americans in Mississippi, and represented a challenge to President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was seeking the Democratic Party’s nomination for reelection; their success would mean that other Southern delegations, who were already leaning toward Republican challenger Barry Goldwater, would publicly break from the convention’s decision to nominate Johnson — meaning in turn that he would almost certainly lose those states’ electoral votes. Hamer, singing her signature hymns, drew a great deal of attention from the media, enraging Johnson, who referred to her in speaking to his advisors as “that illiterate woman”.

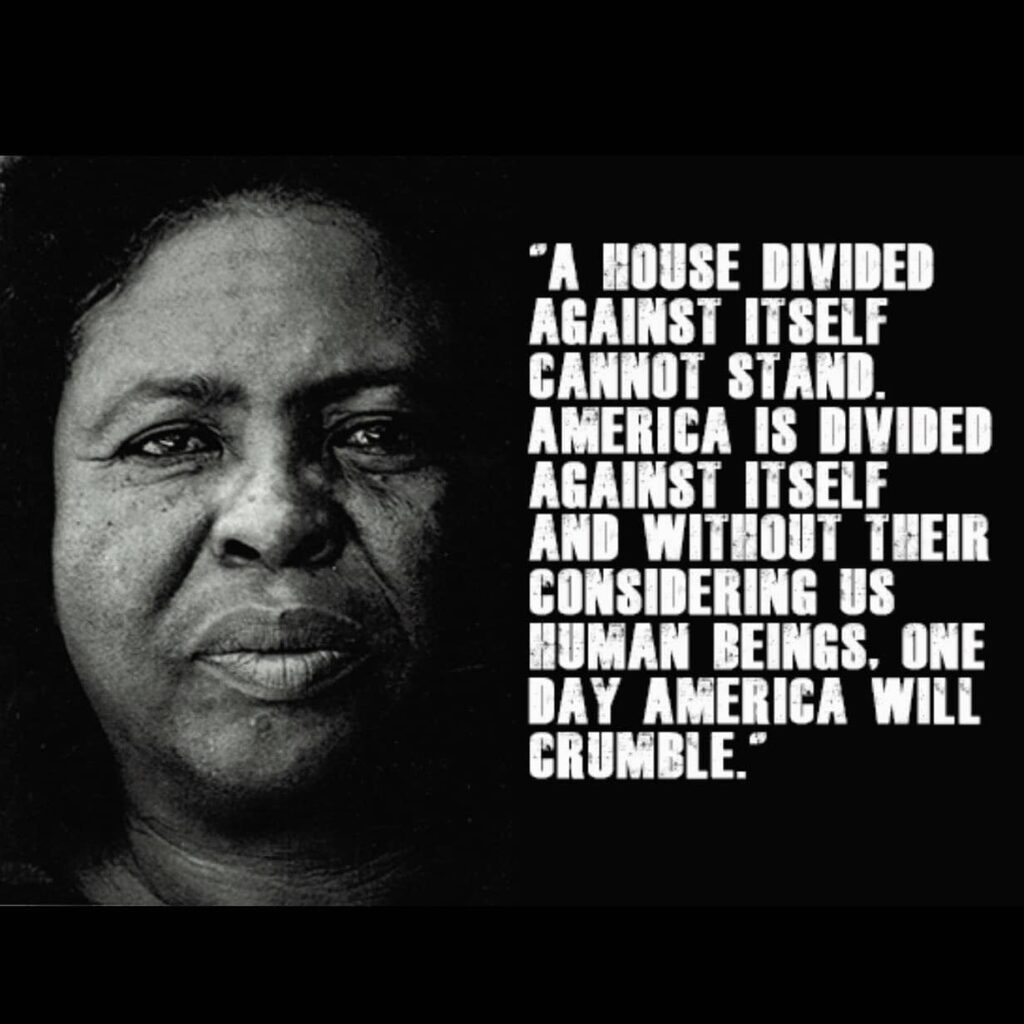

Hamer was invited, along with the rest of the MFDP officers, to address the Convention’s Credentials Committee. She recounted the problems she had encountered in registration, and the ordeal of the jail in Winona. Near tears, she concluded:

In Washington, D.C., President Johnson, fearful of the power of Hamer’s testimony on live television, called an emergency press conference in an effort to divert press coverage. The television networks switched to the White House from their coverage of Hamer’s address, believing that Johnson would announce his vice-presidential candidate for the forthcoming November election. Instead, to the bemusement of journalists, he arbitrarily announced the nine-month anniversary of the shooting of Texas governor, John Connally, during the assassination of John F. Kennedy. However, many television networks ran Hamer’s speech unedited on their late news programs. The Credentials Committee received thousands of calls and letters in support of the Freedom Democrats.

Johnson then dispatched several trusted Democratic Party operatives to attempt to negotiate with the Freedom Democrats, including Senator Hubert Humphrey (who was campaigning for the Vice-Presidential nomination), Walter Mondale, and Walter Reuther, as well as J. Edgar Hoover. They suggested a compromise that would give the MFDP two non-voting seats in exchange for other concessions and secured the endorsement of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for the plan. But when Humphrey outlined the compromise, saying that his position on the ticket was at stake, Hamer, invoking her Christian beliefs, sharply rebuked him:

Future negotiations were conducted without Hamer, and the compromise was modified such that the Convention would select the two delegates to be seated “at large”, with no voting rights. The MFDP rejected the compromise, with Hamer making the famous quote:

In 1968 the MFDP was finally seated after the Democratic Party adopted a clause that demanded equality of representation from their states’ delegations. In 1972, Hamer was elected as a national party delegate.

Political activism and philanthropy

In 1964 and 1965 Hamer ran for Congress but failed to win. Hamer continued to work on other projects, including grassroots-level Head Start programs, the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County, and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign.

- Challenging segregation: Hamer was a driving force behind the MFDP, a courageous effort to challenge the all-white, segregationist Mississippi Democratic Party in 1964.

- National recognition: Hamer’s moving testimony at the 1964 Democratic National Convention brought the MFDP’s efforts and the struggles faced by Black people in the South to national prominence.

- Grassroots mobilization: Hamer played a crucial role in organizing Freedom Summer in 1964, which brought hundreds of college students, both Black and white, to Mississippi to assist with African American voter registration and education in the face of intense segregation.

- Freedom Farm Cooperative (FFC): Recognizing the link between racial and economic justice, Hamer launched the FFC in 1969 to address the economic hardships faced by African Americans in the Mississippi Delta.

- Providing opportunities: The FFC provided land ownership, employment, and various support services like financial counseling and housing assistance, says the National Women\’s History Museum.

- Addressing poverty and food insecurity: She also started a “pig bank” to provide free pigs for Black farmers and initiated programs to address malnutrition in her community.

- National Women’s Political Caucus: Hamer co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971, advocating for women’s rights and their full inclusion in the political sphere, according to the National Women\’s History Museum.

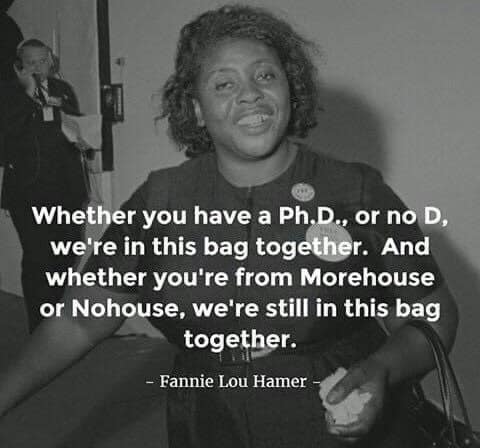

- Building solidarity: She stressed the importance of unity among women, famously stating, “A white mother is no different from a black mother. The only thing is they haven’t had as many problems. But we cry the same tears”.

- Head Start programs: Hamer started a child care center and brought the Head Start program to rural Mississippi to address the needs of children of working mothers.

- Housing initiatives: She helped build low-income housing units through Young World Developers.