This Day in Black History: February 8

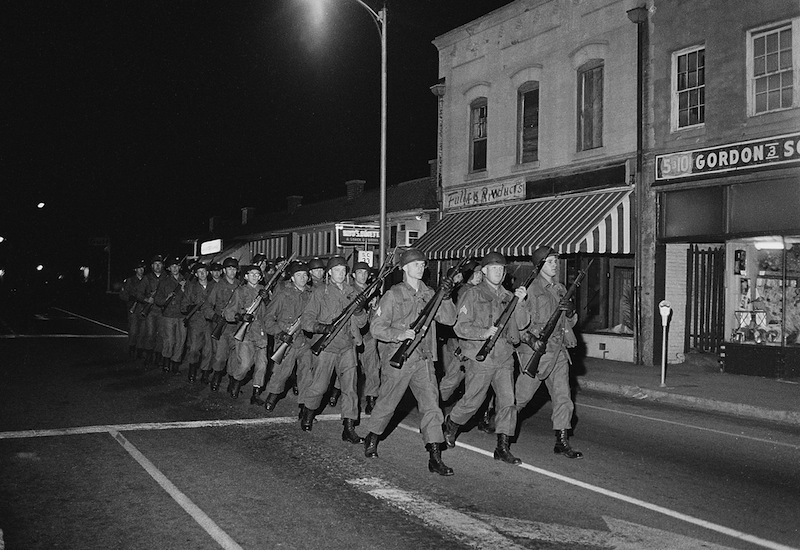

South Carolina National Guard troops marching in the streets of Orangeburg, South Carolina, February 1968, image by Bill Barley, courtesy of South Carolina Political Collections, University of South Carolina.

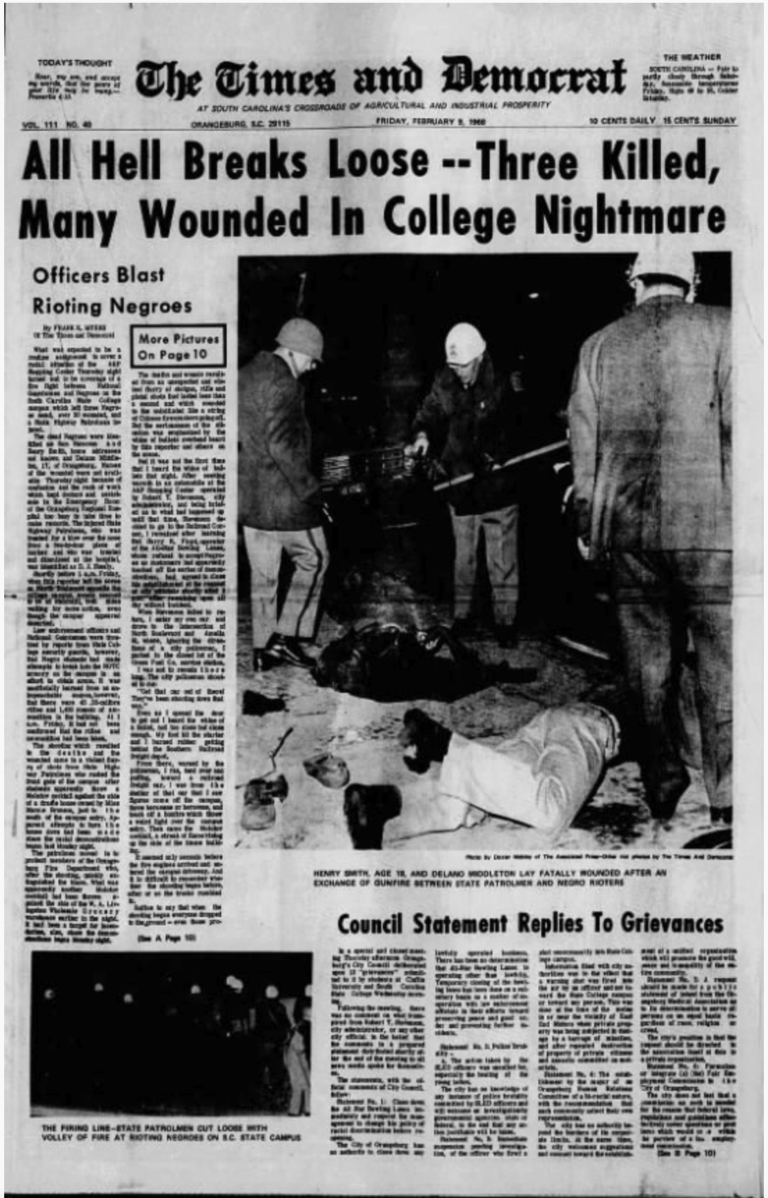

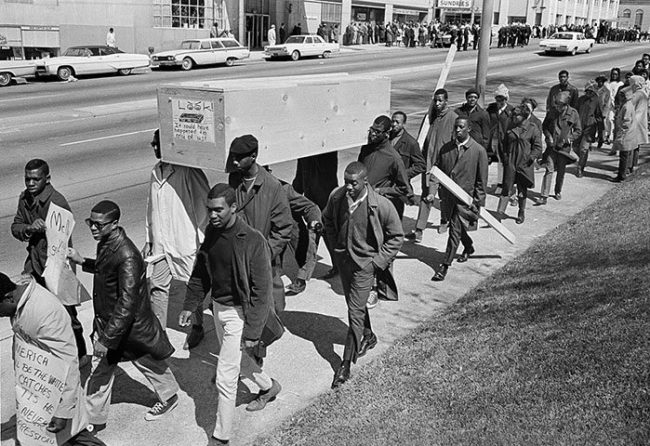

National Guardsmen back up highway patrolmen who charged firebomb-throwing Black students near the main entrance to the South Carolina State College in Orangeburg, S.C., Feb. 12, 1968. Black protesters called for the immediate removal of the National Guard troops from the city and made plans for a boycott of white businesses during a a week of racial violence that left three dead and some 50 people injured.

Bettmann Archive via Getty Images

National Guard troops in Orangeburg, South Carolina, February 1968 (Bill Barley)

“

Remembering the 1968 Orangeburg Massacre When Police Shot Dead Three Unarmed Black Students

The Orangeburg Massacre | Outside The Lines

National Guard troops in Orangeburg, South Carolina, February 1968 (Bill Barley)

The following factors contributed to the conflict:

1. Persistent Segregation and Economic Inequality

The Bowling Alley Dispute: The immediate spark was the refusal of Harry Floyd, owner of the All Star Bowling Lane, to desegregate his facility despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

De Facto Segregation: Beyond the bowling alley, many other local institutions in Orangeburg—including doctors’ offices and the regional hospital—remained segregated in 1968.

Political Disenfranchisement: Although Orangeburg had a majority Black population and was home to two Black colleges (South Carolina State and Claflin), political and economic power was held almost exclusively by White residents.

2. Escalation of Protests and Police Brutality

Initial Confrontations: During protests on February 5 and 6, police used billy clubs to beat students, including female protesters, which “incensed” the student body and heightened the sense of grievance.

Property Damage: Following the police beatings, some students broke windows of white-owned businesses as they returned to campus, which fueled White residents’ fears of “urban terrorists” similar to those seen in recent riots in Detroit and Newark.

3. Aggressive Law Enforcement Response

Militarization: Governor Robert McNair activated the National Guard and sent in hundreds of Highway Patrol officers and SLED agents. By February 8, the campus was cordoned off by over 100 heavily armed officers and army tanks.

Breakdown in Communication: The influx of outside state officials reportedly disrupted existing communication channels between local White leaders and the Black community.

Unfounded Rumors: Law enforcement acted on unfounded rumors that “Black Power” activists planned to burn down the city or attack utilities, leading to a highly defensive and aggressive posture.

4. The Immediate Trigger for Gunfire

The Bonfire and Chaos: On the night of February 8, roughly 200 students gathered around a bonfire on campus. When an officer was injured by a thrown object, law enforcement moved to extinguish the fire.

Misinterpretation of Gunfire: Chaos erupted when a deputy fired a shot into the air to “calm the crowd.” Other officers, believing they were being shot at by protesters, opened fire with shotguns and buckshot for approximately eight seconds.

Unarmed Targets: Investigations later confirmed that the students were unarmed, and the majority of those killed or injured were shot in the back or the soles of their feet as they attempted to flee.

The legacy of the Orangeburg Massacre is preserved through the life of activist Cleveland Sellers and several key landmarks on the campus of South Carolina State University and the surrounding city.

Cleveland Sellers:

Activism and Justice

Cleveland Sellers (born 1944) was a prominent leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) who became the primary scapegoat for the massacre.

Cleveland Sellers, center, stands with officers after his arrest in Orangeburg, S.C., where three were killed and 28 others wounded on Feb. 8, 1968. AP Photo

-

Targeting: Because of his ties to “Black Power” advocate Stokely Carmichael, authorities viewed Sellers as an outside agitator.

-

The Conviction: Despite being wounded himself during the shooting, he was the only person convicted and served seven months in prison for “inciting to riot”.

-

Vindication: Sellers was finally granted a full pardon in 1993. He went on to have a distinguished career in academia, serving as the director of African American Studies at the University of South Carolina and later as the president of Voorhees University.

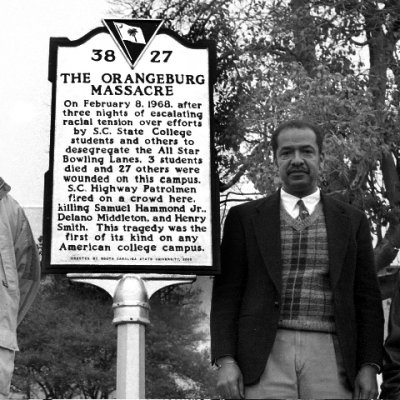

Cleveland Sellers stands beside the historic marker on the S.C. State University campus at the 2000 Orangeburg memorial. By Cecil Williams.

“The names of the three young men killed in Orangeburg were included in a special standalone page headlined “In Memoriam to the Martyrs,” which also included the names of five Black Africans executed by the white supremacist regime of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Saying that the three were “assassinated by government troops in Orangeburg, South Carolina,” the editors of Freedomways published this memorial in an issue which, due to another tragic murder in April, would turn into a tribute issue to Martin Luther King, Jr. In that sense, this homage to the Orangeburg “Martyrs” also became a tribute to the internationalist spirit of King himself, and what he referred to as the evil “triplets” of militarism, racism, and economic exploitation.

No one was ever convicted of the murder of the three young men in Orangeburg; nine officers were indicted for firing on the protesters, but all were acquitted. It was not until 2001 that a governor of South Carolina—Jim Hodges—even attended a ceremony commemorating the tragic events of February 8, 1968. Meanwhile, the only person convicted of a crime in connection with the massacre was SNCC activist Cleveland Sellers, who served seven months in prison on charges of having incited a riot.”