CLIPPED FROM

The New York Age

New York, New York

05 Apr 1906,

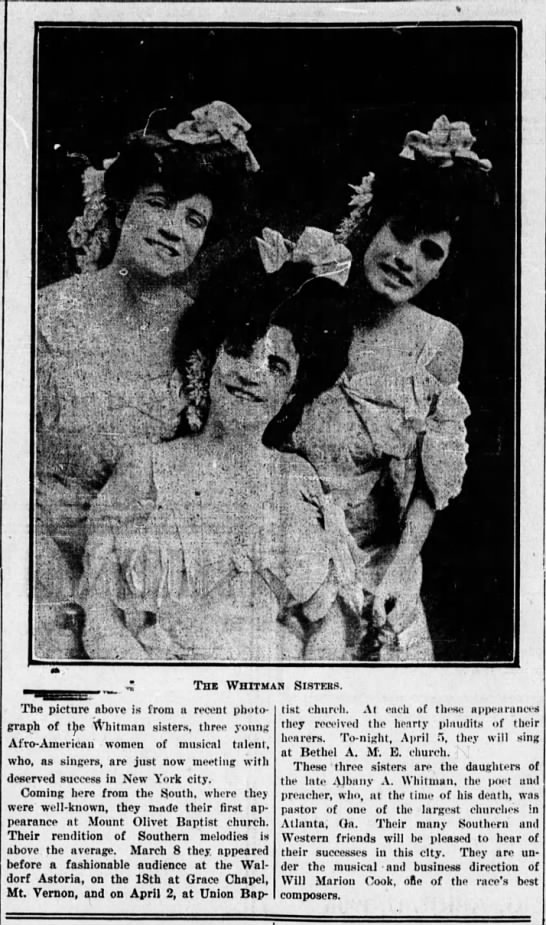

The Whitman Sisters: Why We May Never Silence Them

“Black Voices, White Visions.” Such was the subtitle Marybeth Hamilton (2007) reserved for her book “In Search of the Blues”, in which she argues that the concept of the Delta Blues emerged in the late twentieth century mainly as the product of a longstanding white fascination with the voices and music of the African Americans in a form unadulterated by modernization. In his “History of the Blues” (1995; 2003), Francis Davis muses on how, at any given point in time, “whites have been the ones who have determined what the blues was supposed to mean” (243). It would, moreover, he continues, not be surprising to find that after all, it was the whites who named the blues.

This White vision of the blues has been rightly challenged, implicitly, and explicitly, in the last decades by new insights. Authors such as Molefi Kante Asante stress the importance and necessity of an approach based on (pan-)African cultural concepts in contrast to the dominant Western Eurocentric paradigm. Lawrence W. Levine demonstrates how promising it is to interpret blues music as one phase of a constant social and cultural development of the African American population, faced with the all-over compassing reality of, first, slavery and then racial segregation. Sterling Stuckey convincingly shows how Africans culturally united in the American colonies around the “ring shout” as the cornerstone of their ritual life. Out of the “ring shout” grew the field hollers, work songs, spirituals, and later blues and jazz. African American culture and music are in Samual A. Floyd’s view a permanent process of signifying, the reinterpretation of former genres. Janzhein Jahn has drawn our attention to the central role of “nommos”, the power of the word in African culture. The sound of the word is not only central to African American music; vocal music is itself a constituent element of African spirituality. The word is music, it gives life.

Equally promising is the growing recognition that we need to look beyond the legacy in the form of waxed output or sheet music booklets to paint the story of the pre and proto-blues. By definition, this legacy is culturally biased, and every effort should be made to start exploring all contemporaneous information sources, however, scattered and incomplete, to get the full picture. Obviously, we have to remain critical also on the latter because they are the product of their time, but authors as Abbott and Seroff have nonetheless shown the wealth of data that is still there to investigate. The richness of information spread over local journals and magazines reporting on African-American entertainment and performances is extraordinary. In a recent essay, I could draw from Abbott’s and Seroff’s explorations to present Butler May, who died in 1917, only 23 years old, and who left no aural traces. Nevertheless, the reports of contemporaneous culture critics persuasively demonstrate the seminal role of this black vaudeville performer in the dissemination of the blues idiom.

The appreciation of his monumental role has only been possible by Abbott’s and Seroff’s assiduous research of the articles on his performances in regional and local black magazines and journals, by analyzing what the black vaudeville meant for the African American population, and how Butler May creatively interacted with this environment. In what follows, I am thrilled to tell you the story of the Whitman Sisters, who left no records either, not even sheet music, and whose name – despite their stunning career of some 40 years in black and white vaudeville entertainment – rings a bell only to a few aficionados. We owe it to the brilliant work of Nadine George-Graves (2000), who, as Abbott and Seroff did, dived into local and regional journals and magazines, and made a most illuminating investigation of the sister’s role from the perspective of the historical and social position of African-Americans.

Their study will allow me to conclude my essay by showing how the fermentation of the blues and the astonishing career of the Whitman Sisters were in fact both exponents of the way African Americans have sought confirmation of their identity in American society.

“But, I will not anticipate my conclusions. Allow me to introduce you now to the magnificent and beautiful sisters Mable, Alberta, Alice, and Essie Whitman. Once you will have met them, you will rightly ask the question of how history could possibly have silenced them when, at the end of their career, they are reported to have employed and worked with more than 120 artists, knowing too that for many of them the Sister’s Company was the springboard of later success. To name only a few: Shelton Brooks (1886-1975), popular music and jazz composer; William Basie, aka Count Basie (1904-1984), seminal jazz musician and composer; Butterbeans and Susie, the famous top comedic music act from the ’20s through the ’50s; Lonnie Johnson (1899-1970) who pioneered the role of jazz guitar and made his name as jazz and blues legend; Billy Kersands (1842-1915), who in the late 1800s was the most popular Black comedian and blackface minstrel; Princess Wee Wee (1892-???) who made fame as a professional midget, performing also in the Barnum & Baily Circus; Ma Rainey (1886-1939), commonly billed as the Mother of the Blues; Clarence “Pinetop” Smith (1904-1929), who in 1928 recorded his influential “Pine Top’s Boogie Woogie,” one of the first “boogie woogie” style recordings to make a hit, and which cemented the name for the style; Ethel Waters (1896-1977), who began her career as a blues performer and later became jazz and gospel vocalist, and actress…”

ROOTS IN SACRED MUSIC AND POETRY

The Whitman Sisters started their performances, in various combinations, already in the 1890s and were, with their traveling roadshow of singers, dancers, comics, and a complete music band, regarded as the best of black entertainment until the beginning of the 1940s. In popularity, they competed with the Smart Set Company, an innovative and popular Black vaudeville show, and with The Black Patti Troubadours built around Sissieretta Jones, a pioneering African American concert singer who toured for more than two decades bringing both operatic arias alongside minstrel songs and vaudeville acts.

The Whitman Sisters however were unique, not only because they outlasted the other Black companies, but also because it was the sole company owned and managed by an African American woman, Mabel Whitman, the eldest of the four sisters.

Mabel Whitman

(source: Nadine George-Graves, 2000)

“Vaudeville and dancing were however not the paths that their father had in mind for them. Their father, Albery Whitman, born in 1851 to slave parents in Kentucky, was one of the most prolific and major poets of the nineteenth century. He came under the influence, not only of alcohol (which was to shorten his life) but also of Daniel A. Payne, a major leader and shaper of the AME (African Methodist Episcopal Church), whose conservatory signature was evidenced for instance by his restless fight against the traditional African practices in the church. While introducing instrumental music into the church practice, he stressed simultaneously the importance of having trained choirs. This ran firmly against the spontaneity and improvisation, characteristic and even essential to African American spiritual life. Albery Whitman became a pastor but was moved from church to church.

Rev. Whitman was a light-complexioned man, as was his wife Caddie Whitman of whom it cannot be excluded that she was legally white. The daughters inherited the parents’ complexions. However, they would remain proud to be African American and would prefer to be “Queens of the Toby”, rather than circulate the white circuit for which their light complexion would not have been an obstacle.

The AME church was the first stage environment of Albery and Caddie Whitman’s daughters. Though their father taught them, for “playful and healthy” exercise, the “double shuffle” dance, a popular secular dance with antecedents in the “ring shout” (not particularly the dance that the AME church approved of), Albery Whitman’s training was mainly aimed at preparing his daughters to accompany him on his Evangelical tours. The role he assigned them was to provide the musical backdrop to his preaching. Their singing was, likely, limited to spirituals. After all, the Whitman family profiled itself as a religious family that strived for respectability. It was a time when women’s performance in the theater was considered unrespectable. A respectable church performance was the venue of the Whitman family.

FROM JUBILEE TO POPULAR SHOW AND VAUDEVILLE

Suffering from pneumonia, probably aggravated by his drinking problem, Rev. Whitman passed away in June 1901, at the age of 50. A year before, his youngest daughter, Alice was born. Her sisters were by then 21 (Mabel), 19 (Essie), and 14 (Alberta). Under the attentive “chaperone” eye of their mother Caddie, Essie, and Mabel had already shifted from an exclusive jubilee gospel repertory, aimed at raising money for the ministry of their father and for other church activities, to an act that included also secular songs. It is not quite clear how their father reacted to this repertory redefinition, but it is reported that he finally allowed his daughters to tour on the vaudevillian circuit.

In 1899, Mabel and Essie Whitman made their first steps on the stage, with their own repertory of jubilee songs, but with a clear popular twist to it, different from the style typical of groups like the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Perry Bradford, who would later bring Mamie Smith to the Okeh Recordings studio, claimed that Whitman’s swinging style was new in spiritual singing. Having seen the sisters before they turned professional, he confirms that already from the beginning there was something “different” about the way they sang the old jubilee spirituals: “ the audience”, he remembered, “sat spellbound to hear May [Mabel], Essie and Alberta, those three gorgeous “ofay-gee-gwarks” (meaning in theatrical language ‘high yellow’) chirping out Negro Spirituals.” (Reed, 2010). Their performance style definitely met with success, stimulating the young girls to include even more popular songs in their stage acts. The same year, they toured as the “Danzette Sisters” all over the South, from Missouri to Florida, under the personal management of their mother – a most unusual initiative then, when it was common to have white (male) managers – who carefully watched over the respectability of her girls. Their professional debut in Kansas City in 1899 made an instantaneous hit.

Precise information with regard to those early years is missing, but there are indications that they brought their act also to Europe. Though unconfirmed, it is said that they gave a command performance before King George V and other members of the British monarchy. What is certain, however, is that they initially toured the white vaudevillian circuit and that they were one of the few Black vaudeville groups on this circuit. Their light complexion could have easily raised confusion as to their ethnic background.

By 1902, Mabel, Essie, and Alberta were playing to both black and white audiences in Georgia. A local newspaper (Birmingham News) called them the “bright, pretty mulatto girls” with “wonderful voices.” The article continued: “The sisters play banjoes and sing coon songs with a smack of the original flavor. Their costuming is elegant; their manner is graceful and their appearance is striking in a degree as they are unusually handsome” (Smith, 1996). Reportedly, they occasionally worked as an White act and regularly had to use blackface at the insistence of theater managers (id.). It is unmistakable that the way they concluded their act was contributing to their popularity. When they had performed in blackface and wigs, they came out for their encore with natural long blondish hair, leaving the public totally puzzled asking, first, what these white ladies were doing on stage, and then laughing in amazement when it noticed that they were the performers that it had been watching all evening.

The following years corroborated their success. In 1904, the sisters took the name “The Whitman Sisters’ New Orleans Troubadours” and started to integrate other acts in their roadshow. In a matter of only a few years, they had grown into a company of twelve. One of the most famous acts in those early years was doubtlessly a young boy of 12 by the name of Willie Robinson, aka “Bill Bojangles”, who would make fame as a tap dancer and actor in theater stage and movies. His hallmark was his expressive face, and his busy, inventive feet. In the 1930’s he would get a worldwide public, dancing with Shirley Temple. Willie Robinson was only among the first of the many other children, boys and girls (pickaninnies), who would come under the wings, first of Caddie Smith, and later under the maternal eye of Mabel Whitman who trained and mentored them professionally. Alice’s son, Pops Whitman, was also one of the long lists. He developed into one of the greatest acrobatic tap dancers, gaining international fame and touring with several big bands of the thirties (Malone, 1996). The sisters clearly had an eye for young talent and had the skills to turn the young talents into highly professional entertainers.

Though by no means an indication of cutting their ties with the South or with the African American (religious) community, in 1905, the Whitmans moved their formal base of operation from Atlanta to Chicago, where it was to stay for the rest of their career. The move of headquarters was speaking foremost of the broadening of their public to Northern cities. By this time, the three sisters had become very accomplished dancers, as well as exceptionally talented singers, performing not only on secular stages but consolidating their success by continuing to appear in churches. In the company of little Willie “Bill Bojangles”, they spent for instance two weeks in 1908 singing and dancing to overflow crowds in Washington (Baptist) churches. In 1909, they were signed to the Pantages circuit, a highly successful chain of vaudeville theaters and motion picture houses in the United States and Canada, known for their elegancy.

Their mother, Caddie Whitman died in Atlanta in 1909, and shortly after Mabel took over the maternal and managing role. It was under her legendary, tough-minded, fearless but fair style that the Whitman sisters would become wealthy and would launch their show as the “fastest-moving, most professional” one on the circuit. Mabel controlled the life of the group, on and off-stage, seeing to it that at all times moral standards were respected and that the members, as one big family, obtained only the best.

Not later than 1910, the sisters, having played most of the vaudeville circuit on South, East, and North, had acquired the title “Royalty of Negro Vaudeville.” As Count Basie later recalled, their show was second to none. Alice, who joined the show after her mother’s death, figured as the “baby” sister, but she was to become one of the greatest tap dancers around (Malone, 1996), atypical for a period when tap dancing was considered a dominantly male activity. Their show usually featured comedians, a chorus line, female singers, a few sparkling dancers, and a small jazz band. A contemporary comedian described their reputation and popularity poignantly when he said that “they were like the Bible to Negro audiences – people saved up their money for a whole year to hear and see them when their show came to town (id.)” (1996). The story has it that in Pittsburgh in 1911 their success was so overwhelming that the next act could not go on as scheduled because the audience’s enthusiasm did not stop (Smith, 1996).

In the following decades, the company regularly staged between twenty and thirty performers, and sometimes up to 35 members, comprising among others a chorus line of some twelve to fourteen women, and a strong five- or six-piece jazz band. Lonnie Johnson has led this band for nine years (id., 1996). Their show was always fast-paced, a marvelous whirlwind of music, dance, and singing.

Doubtlessly, the continuation of their popularity during several decades, until their final breakdown in the early 1940s’ – Mable died in 1942, reportedly only 62 – was credited to their adaptive capabilities. Faced with the competition of silent movies in the 1930s, they changed the format of their show to fit in between the screenings and just carried on. But, eventually, their uniqueness is due to much more than their sole musical and dancing excellence. Allow me to indulge in those other aspects now, which make them stand out in popular African-American music.

FEMINISTS AVANT LA LETTRE

As said above, women on the theater stage were then not particularly regarded as respectable. A woman’s appearance on stage was looked upon as “vulgar” and “immoral”. Yet, the Whitman Sisters defied the social expectancies on this matter in a truly unmatched way through a straight attack on the traditional role of women in show business. They completely destabilized the existing stereotypes on gender by taking full control of their act and production, simultaneously appealing to the rich and poor classes, to white and black, and to men and women, constantly maintaining moral respectability on and off stage.

The Whitman Sisters ran their own business, and Mabel, following the example set out by her mother, exercised total control of the enterprise. In an environment dominated by male white theater owners and booking agents, in which corruption and racial discrimination were part of the game, Mabel profiled herself as a monumental manager. The “Tiger Show Woman”, as she was often called, mastered as nobody else the ins and outs of show business, and her determination to obtain what she wanted was well known. She was tough and could be intimidating as director and dance coach, and many of the companies even feared her. The output of young talent from the company was doubtlessly due to the iron discipline she installed in the group.

She fully capitalized on the company’s popularity to get the best deals when booking the group in the best theaters. The story is known of the Regal Theater in Chicago which refused to pay the agreed-upon price for the act. Instantaneously, she took her group to the Metropolitan Theater across the street where she had a new stage built, by ruining the Regal’s business for a full two weeks. She would not let herself and her company fall victim to what she called a “set of unscrupulous owners and managers” who syndicated themselves together “to stifle the progress along the lines of art and entertainment” (George-Graves, 2000: 99).

Respectability was a building block of their reputation. Mabel saw to it that moral standards were at all-time complied with both on stage, and off stage. She patrolled the private lives of the company’s members, and parents were totally confident that when they entrusted their children to Mabel’s responsibility for mentoring, there would be no moral missteps. The Sunday visit to the AME church was a mandatory agenda item. Mabel was at the same time preacher, director, mother and manager, and guardian of the group’s morality.

Transcending the line between the secular and sacred entertainment, the church remained for the sisters also a performance stage. By combining theater and church appearances, they kept the bonds with the African-American community active, and their socializing with the church elite helped to profile them simultaneously as a respectable family devoted to charity, in and out of the church. The “adoption” of children for training under Mabel’s maternal responsibility sustained the reputation of the charity.

Their repertory underpinned their socially broad appeal. On the one hand, the Whitman Sisters capitalized on the existing traditions of minstrelsy and vaudeville, mingling it with European elements of the extravaganza, burlesque, and musical revue. On the other hand, they also put their own stamp on them. While keeping high-quality performance standards as benchmarks, they were also the innovators of new dances. They created their very own show of “pretty young girls”, building largely on the traditional African-American dances as they originated in the ring shout. Religious songs were mixed with coon shouts, brought by attractive ladies dressed in expensive attire to promote the respectable image of African-Americans. The expression of individual talent primed to meet the expectancies linked to stereotyped, stock theater characters. The role played by Mabel, on and off stage, was only one example of the renewed, “signified”, interpretation of the traditional idioms: while in one way, she could be seen as the minstrelsy-type black “Mammy”, at the same time her behavior deviated from the traditional “Mammy” when she combined the caring of her “pickaninnies” with that of a tough businesswoman.

In their very own way, the Whitman Sisters were models of both high-level musical performance and of active feminism. The word “resistance” comes to mind when we associate their role model with an (implicit) critique of the ruling standards of their time.

NEGOTIATING GENDER AND RACE

The social role remodeling went even further. Tough they capitalized also on the erotic elements in their performances, by their way of dancing and dressing which highlighted their female elegance and beauty, at the same time the sisters acted in such a way that their dancing was never labeled as “loose”, or could be stigmatized as obscene or morally corrupt. The audience’s attention was constantly focused on the skills of the performers, rather than on the physical presentation. Alice, the “adorable baby”, was one of the only American soloist female tap dancers, hence challenging the contemporaneous gender roles in dancing, but it did not prevent her from being called the “Queen of the taps.” She was an adorable girl and combined her attractiveness with utterly strong dancing techniques. Until succeeded by her son, Albert, “Little Pops”, she was the troupe’s star performer. The recognition of her mastery of the dancing in an era where it was expected that women soloists in show business were in the first place singers, in order not to jeopardize their reputation, strengthened the message Alice sent out to do away with the ruling role models.

In her ravishing femininity, Alice often danced graceful duets with a character called Bert, a fancy-dressed, dapper, neatly dressed “man-about-town”. Bert was nobody else than Alberta Whitman, cross-dressed, who was known as the best male impersonator of her time. Here, also, gender roles were challenged, in a way however that stood miles from the classical nineteenth-century travesty dancing which was often no more than an excuse to “get women into short pants to show off their legs and reinforce dominant sexual norms.” (George-Graves, 2000:77). Alberta Whitman made an art of astonishingly and convincingly changing characters in no more than twenty minutes, reproducing authentic “male style, fashion, and stance” (id.). Her performance was well-received by critics and audiences, and her gender transgression art was an integral part of the top-quality show the sisters constantly endeavored to bring. Cross-dressing, a standard line in show business, was taken to a higher level to fit into the high-class entertainment envisioned by Mabel, Essie, Alberta, and Alice.

Combining high-quality entertainment in theaters and churches, and offering a variety acts that spoke to both sexes, the Whitman Sisters remained popular for all social classes, both Black and White. Much more delicate than the refiguring of class and gender in a period of blatant segregation was however the Sisters’ manipulation of race roles, undermining the notion of a fixed racial identity. Let us indeed not forget that racial identity was a cornerstone of American society and hence also an inescapable element in theater and entertainment. Jumping out of the racial categorization could entail total marginalization, at the least, and physical aggression as an unexceptional reaction.

Nevertheless, the Whitman Sisters displayed on stage the whole gamut of roles from the “darkest dark to the palest of pale”. It was a rainbow of beautiful girls, as George-Graves formulated it so poetically (71). They performed as black acts, sometimes blackening up their faces (using burnt cork or grease paint), and occasionally – especially in their initial career – appeared as an White act. They masterfully slipped in and out racial stereotypes, passing for both Black and White. This way they totally controlled the interpretation of their roles not only related to gender but also to race.

As noted already, the Whitman Sisters sometimes performed in black-haired wigs and blackface, and then, during the finale, took off the makeup and wigs to let their dyed blond hair down when they came back on stage. It left the audience completely puzzled with regard to the racial identity of the performers. The black women were mistaken for white women, who blackened up to remove the dark masker and to appear as black women. Amazing laughter by the public probably concealed complete disorientation with regard to the real racial identity of the women. What was certain? Where they Black or White? Were the White women Black, or were the black women white? Were they white women with blond hair, or Black women with black hair? Total disorientation must have been the public’s fate.

Obviously, their light complexion made it easier to switch racial roles as part of the act. Moreover, the fact that they were female and physically attractive, made the act also seem less offensive and less threatening to the social power relations. Men would have had difficulties doing the same. Anyhow, while gender passing was a more general practice on stage, the frequent passing of skin color and stepping in and out of racial identity was far more complicated and challenging. The reported ease with which the well-dressed and sophisticated Whitman Sisters reversed roles and controlled their gender and race representation on stage must have baffled the public.

ROYALTY OF NEGRO VAUDEVILLE

It is not excluded that Mabel also passed color when she negotiated the bookings of the company, hence assuring better pay. We do not know for sure. What we are certain of, however, is that the Whitman Sisters not only continued to identify in the first place with the African-American community but they were also active agents promoting African-American culture and fighters against racial segregation.

Indeed, the Sisters have unmistakably been an early channel for the dissemination of black dance styles, and have played a major role in creating and popularizing the Black dance idiom to the large public, both black and white. Their show was moreover geared towards a racially mixed audience, probably containing different layers open to different interpretations along the color line. More important, to highlight, however, is their deliberate choice in the early 1920s to work on the TOBA circuit. Despite their possibility to tour with white Northern circuits, they preferred the Toby label to the success that was guaranteed for them on the white, high-class, vaudeville circuit. Undoubtedly, they possessed the talent to follow the path that had shown an artist like Bert Williams the way to Broadway, but the sisters opted for the “Chitlin’ Circuit”, the booking organization for Black artists. The fact that they were the best paid of the TOBA, compared to the general small-time Toby-performers, is less important here than the observation that the Whitman Sisters, as mulatto’s, wanted to remain connected to the African-American community, to stay loyal to the Black audience.

The latter observation acquires extra meaning when we set it out against the backdrop of the active, anti-segregationist policy adopted by the Whitman Sisters. The show was outlined to speak to both the White and Black public, the racial integration of their audiences being a cardinal point of their objectives. As the only black (female) manager, Mabel furthermore used her full managerial skills to obtain the best for her black vaudeville group in a racially segregated theater business. Hardly imaginable in a climate of fierce racial separation, it speaks for the stubbornness and political courage of Mabel and her sisters that they insisted that African-Americans would have access to the parquet seats and the dress circle sections, instead of being relegated to the theater’s balcony. When the Whitman Sisters appeared at the Jefferson Theater in 1904, it was the first time that African-Americans could buy dress circle and parquet seats in this theater, and possibly the first time anywhere in Birmingham. Note that already in the first 3 months of that same year, thirty-one African-Americans were reported to have been lynched, a figure that illustrates a time spirit when hanging, shooting, and burning Black men, women, and children in the United States were so common that such occurrences created but little sensation. In this perspective, the Whitman Sisters’ insistence upon racial integration in the entertainment sector acquires historical significance.

WHERE THE WHITMAN SISTERS MEET THE BLUES

The contrast between the unmatched role played by the Whitman Sisters during several decades of African-American entertainment, and the silencing of which they have been the victim is amazing. It would take us too far to unravel this seeming contradiction. Suffice it here to speculate on the absence of sheet music and aural records as a possible origin (1). Even few photographs can testify of their glory due to the destruction, in 1963, of the Whitman Sister’s Chicago home by a fire that eventually also killed Essie, who was then 81. A more important question to raise is probably why it has taken so long before somebody broke the “institutionalized silencing”, as George-Graves calls it, by digging into the available material present in the contemporaneous press, even if it is mainly in the local black journals. The argument can be made that it was precisely the difficulty of classifying or categorizing the show that has put them, up till now, out of the spotlights of historical research. Just as, at the time, they left their audience puzzled as to who they were, it has been tough to allocate them a precise place in the gallery of African-American entertainment.

The Whitman Sisters cleverly defied the ruling practices about stereotypes associated with class, gender, and race. They made it a key to their success to appeal to an audience that transcended gender and social background, and that clearly questioned the color line, so prominent and dominant during the era of their popularity. Their innovative performance was based precisely on the refiguring of the ruling expectancies attached to gender, class, and race. They promoted the feminist agenda, but at the same time watched carefully to abide by the respectable role model of the “Mammy”. The sisters attached major importance to keeping the link with their African-American roots, whilst at the same time emphasizing the primacy of elevating the status of the Black population. Theirs was a repertory that creatively combined the traditions of minstrelsy, coon songs, and vaudeville with the standards set by high-class performance. The white audience was an important segment of the public, but simultaneously they were not afraid to tear down the racial barriers set by Jim Crow. Whilst the white circuit was a pecuniary a much more attractive circuit, they nevertheless dedicated themselves for the largest part to the Black audiences. They were mulattos, but they never even alluded to the tragic elements often embedded in this archetypical mixed-race person, who is commonly expected to be sad or even suicidal, being the victim of a society divided by race, failing to be integrated into neither the Black nor the White part of society.

Yet, I discover in the sister’s very questioning of the rigid racial roles, in their creatively slipping in and out of stage characters defined by the performer’s complexion, another illustration of the many ways that the African-American population has tried to define its very own place in a blatantly racially divided society. When the Reconstruction efforts had definitely but, not unexpectedly, failed at the end of the 1870s, the African-Americans were left not only at their own mercy but soon found out that economic, social, and political mechanisms had efficiently replaced the old slavery chains. The hope of emancipation, present in the aftermath of the Civil War, was violently thrown to pieces. Whilst during slavery, the African-Americans had a clear place in society linked to an unambiguous social identity, both had to be redefined in the latter part of the 1800s.

At the political level, this redefinition was promoted by W.E.B. Du Bois opposed Booker T. Washington’s ideas of seeing the Southern blacks obtaining educational and economic opportunities in exchange for submission to the white class. For Du Bois, there was no discussion about the goal that blacks should enjoy the same civil and political rights as the white population. I see the same emancipation drive also filter through in the entertainment sector, though there was little attention paid by black political “activists” to the latter sector, in which the search for their own Black identity was an independent ferment, growing from the bottom of the population. The Whitman Sisters’ incessant destabilization of stereotypes was their way of paying attention to the value of the individual performer, irrespective of gender, social background, and even the color of the skin. In their continuous emphasis on high-quality show business, explicitly identifying themselves with the African-American community, they were a live example of the emancipatory potential of the latter. In their way, Mabel, Essie, Alberta, and Essie Whitman set a role model that could lead to rebuilding a society hopelessly divided by cruel racial barriers. It was a message, not of despair, but of hope.

I would like to argue that the blues idiom, which fermented in the same era, was another way of expressing the need for constructing a new identity, and the will for self-definition in a society where African Americans were deprived of any role other than being a disposable element of the labor force. During the decades following the Civil War, Black entertainment had adopted the minstrelsy format that heralded the good old plantation times or had cleaned up the Negro spirituals sufficiently to be presentable on the White and international scene. In the same line, the coon songs, and the rag-time music, infused with European musical components, brought also by Black artists, were essentially nothing more than the assimilation of how the white population confirmed its stereotypical view of the “darky”. In the blues idiom, and also in jazz, we notice a thematic acquisition by the African-American who sings about topics that matter to him, independently from the images and subjects imposed upon him by White mainstream entertainment. The blues songster expresses his worries and muses about themes that are relevant to him, and through him, to the group to which he belongs. This thematic redefinition is an emancipatory act. Most importantly, the blues idiom builds upon the African cultural memory; it is a reinterpretation, a “signifying”, of the slave sounds and, hence, ultimately an actualization, in a secular context, of the “ring shout”.

Thus, in the same way, as the Whitman Sisters made an unambiguous social statement that needs to be interpreted in the context of racial uplifting and self-empowerment, so can we see the blues, and jazz, like other media through which African-Americans continued to stress their own identity and value, in the face of a society that refused to recognize them. From this vantage point, the blues is not primarily a “cry of despair”, or a testimony of the pain of alienation, such as it is commonly portrayed in our popular understanding, but rather an act of self-assertion. The former view on the blues stems foremost from a definition advanced by white scholars and aficionados and says probably more about themselves, their ideology, and motivation, than about the subject itself. If I look at the fermentation of the blues idiom in its historical context, as a developmental phase in the black culture and consciousness (Levine), I see in the first place the effect of the constant optimism, typical for the African culture, of a people that fights for its rightful place. Certainly, we could hear in the blues the moaning and disheartening voice of a deprived group, echoing the slave’s field hollers, but I prefer to read in the blues foremost a message of hope, and confirmation of pride in their African-American culture. The blues is, if not an act that shows the ability of the African-American to get a grasp on his destiny, it is certainly an expression of assertiveness and hope.

The observation that the Whitman Sisters walked the path of emancipation and independence by seeking full control of their stage identities, and by shattering the stereotypes defined by White mainstream, and that the blues songster did so by incorporating in his repertory the themes that mattered to him, disregarding the socially imposed stereotypes inspired by the slave on the plantation, or by the ridiculed urban dandy, is eventually of secondary importance. At the end of the day, it is the affirmation of the right to control the way one presents oneself that primes.

Footnotes

(1) In 1921 Essie Whitman and her Jazz Masters, accompanied by Fletcher Henderson, recorded blues songs for the Black Swan Label (Black Swan 2036, 1921, reissued on Document DOCD-5342) (Lynn Abbott & Doug Seroff, Out of Sight, 2002, 442)

Further reading:

– Nadine George-Graves, The Royalty of Negro Vaudeville, 2000

– Jessie Carney Smith, Notable Black American Women, Book II, 1996

– Bill Reed, Hot from Harlem, 2010

– Jacqui Malone, Steppin’ up the Blues, 1996

– http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/learning_history/lynching/terrell.cfm

Source: www.myblues.eu