Page 2 – 6

WOOLWORTH SIT-IN WAS THE MOST VIOLENT OF MORE THAN 300 SIT-INS TO END SEGREGATION

“Their courage, captured in a defining moment of the Civil Rights Movement, helped pave the way toward the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, the Tougaloo student activists were part of a larger strategy for a domino effect of eliminating segregation. Lewis was the NAACP North Jackson Youth Council President, and Moody and Norman were Tougaloo student activists. They put the plan together with Medgar Evers, then the NAACP Field Secretary.

After the sit-in progressed to violence so quickly, Evers wanted to call the sit-in off, but the activists refused. They wanted to sit it out literally. The bullying, violence, and verbal humiliation lasted for three hours, with police inside the facility watching the attacks.”

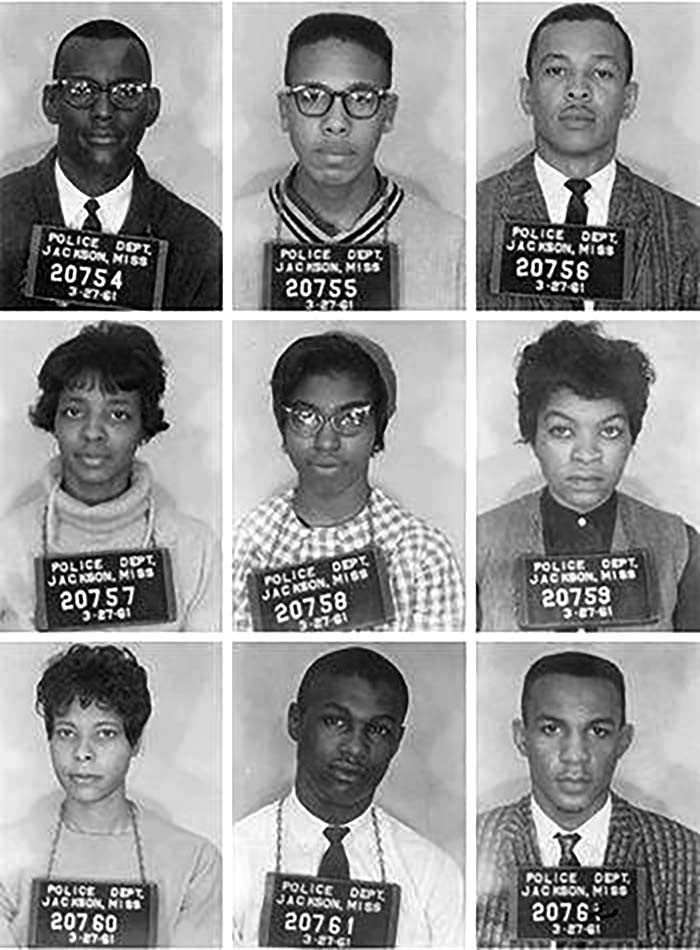

Tougaloo Nine: (from top left) Joseph Jackson Jr., Albert Lassiter, Alfred Cook, Ethel Sawyer, Geraldine Edwards, Evelyn Pierce, Janice Jackson, James Bradford, and Meredith Anding Jr., 1961

Fair use image, Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History

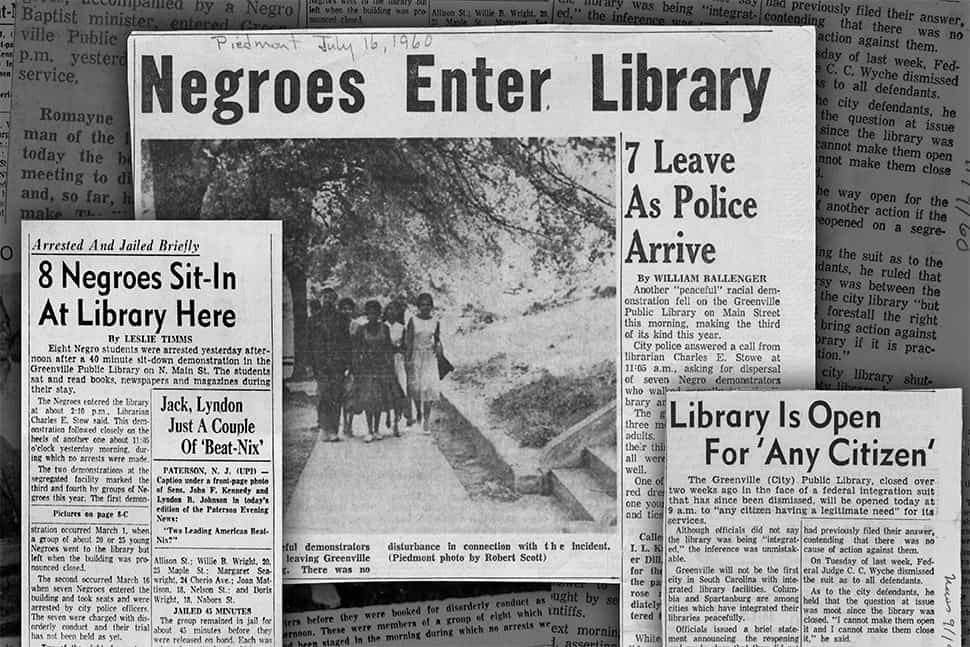

Clippings from The Greenville News and The Piedmont, courtesy of the Greenville (S.C.) County Library System

“At 11 a.m. on March 27, 1961, nine students from the historically Black Tougaloo College walked into the all-white Jackson (Miss.) Public Library. Joseph Jackson Jr., their leader, approached the circulation desk. With heart thumping, he stammered a message he had memorized: “Ma’am, I want to know if you have this philosophy book. I need it for a research project.”

“You know you don’t belong here!” the library assistant yelled, proceeding to call the library director.

“May I help you?” the latter asked, coming out of her office.

“We’re doing research,” the students responded.

“There’s a colored library on Mill Street,” she said. “You are welcome there.”

Almost immediately, Jackson later reported, police entered the building and told the students to get out of the library. No one moved. The chief of police then told them that they were under arrest.

Six officers placed the students into squad cars and at the station charged them with breach of the peace because they failed to leave the library when ordered. They were booked into the local jail, where each was held on a $500 bond.

In jail that evening, the students worried. “Reflecting on Emmett Till [murdered in 1955] and the history of lynching connected with Mississippi,” Jackson related in 2015 to writer Gabriel San Román in the Orange County (Calif.) Weekly, “the later it got that night, I was in fear for my life.” He began rehearsing what he would say if the Ku Klux Klan came for them: “Please, Mr. Klansman, don’t hang me. I have a wife and two little children in Memphis, and if you release me this night, I promise you I will never, ever come back here to Jackson and violate your Jim Crow laws.”

His colleagues laughed at his naiveté. “You know what the Klansman would say?” one said. “‘Nigger, you should have thought of that before you entered our segregated public library!’”

Several days later, the students were taken to the courthouse to be tried. Several blocks away, hundreds of whites were marching through city streets under a huge Confederate flag. At the courthouse, however, some 100 black supporters had gathered to cheer what was now referred to as the “Tougaloo Nine.” Fourteen police officers and two German shepherds lined the courthouse stairs.

When the crowd began to applaud the nine students as they arrived, the police chief yelled, “That’s it! Move ’em out! Get ’em!” Police set upon the crowd with nightsticks and dogs. During the melee, Medgar Evers (secretary of the Mississippi chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People [NAACP], who would be assassinated two years later) and several women and children were pistol-whipped, two black ministers were bitten by the dogs, and an 81-year-old man who went to the courthouse only to hear the case suffered a broken arm when police beat him with a club.

The brutality exercised on Black people supporting the library protesters in Jackson, Evers later argued, set in motion broader desegregation activities in Mississippi. “This act on the part of the police officials brought on greater unity in the Negro community and projected the NAACP in a position of being the accepted spokesman for the Negro people,” he wrote in his autobiography.” – American Library Association

What other sit-ins did Tougaloo students participate in?

Jackson Woolworth’s Sit-In in 1963.

- On May 28, 1963, Tougaloo students and faculty, including sociology teacher John Salter and students Joan Trumpauer and Anne Moody, staged a sit-in at the segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in downtown Jackson, Mississippi.

- This particular sit-in is known for being one of the most violent of the era, where the peaceful demonstrators endured insults and attacks from a white mob for several hours.

- The activists were pelted with objects from the lunch counter and covered in sugar, mustard, and ketchup.

- Despite the severity of the attacks and the inaction of observing FBI agents, the activists continued their peaceful protest, demonstrating remarkable courage and commitment to the cause of desegregation.

©Iforcolor.org – Dale Ricardo Shields (2024)

RESEARCH DOCUMENT

Educational material / Entertainment

[ NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED ]