Page 5 – 6

What is the history of Tougaloo College?

Historical Information

It was first chartered in 1871 and named “Tougaloo University”. The “Normal Department” of Tougaloo served as a teacher training school until 1892, at which time it no longer received state funding. In 1916, Tougaloo University was renamed Tougaloo College.

Tougaloo College is a private, coeducational, historically Black four-year liberal arts, church-related, but not a church-controlled institution. It sits on 500 acres of land on West County Line Road on the northern edge of Jackson, Mississippi. In Good Biblical Style, the Amistad, the famous court case that freed Africans who were accused of mutiny after they killed a part of the captor crew of the slave ship Amistad and took over the vessel, begat the American Missionary Association. The American Missionary Association begat Tougaloo College and her five sister institutions.

In 1869, the American Missionary Association of New York purchased five hundred acres of land from John Boddie, owner of the Boddie Plantation, to establish a school for the training of young people “irrespective of religious tenets and conducted on the most liberal principles for the benefit of our citizens in general.” The Mississippi State Legislature granted the institution a charter under Tougaloo University in 1871. The Normal Department was recognized as a teacher training school until 1892, at which time the College ceased to receive aid from the state. Courses for college credit were first offered in 1897, and in 1901, the first Bachelor of Arts degree was awarded to Traverse S. Crawford. In 1916, Tougaloo University’s name was changed to Tougaloo College.

Six years after Tougaloo College’s founding, the Home Missionary Society of the Disciples of Christ obtained a charter from the Mississippi State Legislature to establish the Southern Christian Institute (SCI) in Edwards, Mississippi. Determining later that Tougaloo College and SCI had similar missions and goals, the supporting churches merged the two institutions in 1954 and named the new institution Tougaloo Southern Christian College. Combining the resources of the two supporting bodies, the new institution renewed its commitment to educational advancement and the improvement of race relations in Mississippi. The alumni bodies united to become the National Alumni Association of Tougaloo Southern Christian College. In 1962, by a vote of the Board of Trustees and the supporting bodies’ agreement, the name was changed again to Tougaloo College.

Tougaloo College has gained national respect for its high academic standards and level of social responsibility. The College reached the ultimate demonstration of its social commitment during the turbulent years of the 1960s. During that period, Tougaloo College was at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, serving as a safe haven for those who fought for freedom, equality, justice, and the sanctuary within which the strategies were devised and implemented to end segregation and improve race relations. Tougaloo College’s leadership, courage in opening its campus to the Freedom Riders and other Civil Rights workers and leaders, and its bravery in supporting a movement — helped change the state’s economic, political, and social fabric of Mississippi and the nation.

Aside from its social commitment, Tougaloo College has continued to strive to create an environment of academic excellence and a campus of engaged learners. The administration and faculty continue to challenge students to be prepared to take advantage of opportunities available in a global economy and to become leaders who will effect change. The faculty has grown in quality and size, diversity has been enhanced, and the physical landscape and campus infrastructure are evolving. New curricula have been added. Partnerships and networking relationships have been established with many institutions such as Brown University, Boston College, Tufts Medical and Dental BTougaloo College has moved forward on many different fronts. Its graduates are distinguished and engaged in meaningful work throughout the world. As the College navigates through the twenty-first century, student success remains our highest aim – ensuring that they are prepared to meet the global challenges of a changing world.

The founders continue to light the way as each who has gone before has cut this road to last.

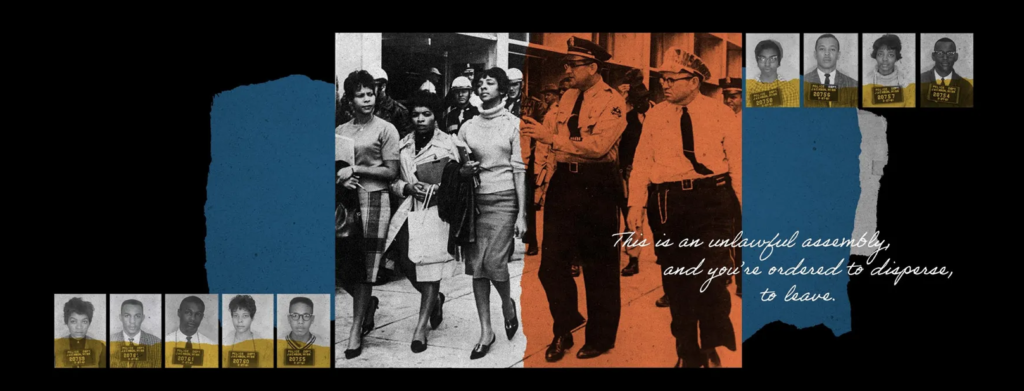

ILLUSTRATION: ANDREA BRUNTY, USA TODAY NETWORK

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/today-our-history-september-7-1962-tougaloo-nine-protest-hardison?trk=articles_directory

“American Library Association membership adopted the “Statement on Individual Membership, Chapter Status and Institutional Membership” which stated that membership in the association and its chapters had to be open to everyone regardless of race, religion, or personal belief. Four state chapters withdrew from ALA: Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

The Civil Rights Movement began slowly in the South, especially in Mississippi. Before 1955, it was mostly isolated protests against the obstruction of voting rights for Black Americans. Groups formed during this period include the Mississippi Progressive Voters’ League and the Regional Council of Negro Leadership. In the 1960s, more youths began to participate in the Civil Rights Movement.

Mississippi was considered by civil rights organizer Medgar Evers to be “too racist and violent” for lunch counter sit-ins so the public library was chosen because it was supported by both Black and White taxpayers. The students, trained in nonviolent resistance, were NAACP Youth Council members led by Joseph Jackson Jr.

On March 27, 1961, they visited Jackson’s library for Black residents, George Washington Carver, and requested books they knew were not there. They then entered the main Jackson Public Library for white residents and staged a “read-in.” The nine students began to search for source materials for class assignments, sat down in the library, and began to read. At this time, the library staff called the police. They were told “There’s a ‘colored’ library on Mill Street… You are welcome there.” When they refused to leave, they were arrested and charged with breach of the peace for failing to leave when ordered to do so. That following day, on March 28th, the nine students were released on a one-thousand dollar bond.

The day after the Read-In, fifty students from Jackson State College picketed the arrest of the Tougaloo Nine before their release. Police utilized clubs and dogs against the students to disband the protest. The next day, March 29th, over one hundred Black community members congregated outside of the courthouse to show support for the Nine as protesters applauded the arrival of the Tougaloo Nine at the courthouse, policemen set on the crowd with dogs and nightsticks resulting in the beating of NAACP representative Medgar Evers along with several women and children, two men being bitten by dogs, and an 81-year-old man suffering a broken arm when police beat him with a nightstick. Reverend S. Leon Whitney, a pastor of Farish Street Baptist Church, was among those bitten by police dogs.

Medgar Evers later reflected “This act on the part of the police officials brought on greater unity in the Negro community and projected the NAACP in a position of being the accepted spokesman.” A Jackson reporter summarized the event by saying, “A quiet community has been invaded by rabble-rousers stirring up hate between the races, and following are the…publicity media feeding an integrated North the choicest morsels from the Mississippi carcass.… The Negro who has so long held the guiding and helping hand of the White may lose that hand as he climbs the back of his benefactor and teacher to shout into halls where he is not welcome. ”

The students appeared in court on March 29th and were not allowed to see their attorneys Jack Young and R. Jess Brown before their hearing. They were fined $100 each and given a thirty-day suspended sentence and a year’s probation on condition that they “participate in no further demonstrations. ”

In protest of the sentencing and the brutality of police towards bystanders, a meeting was held at a local Masonic Temple, at which Julie Wright encouraged other Black community members to participate in a “No Buying Campaign”. This campaign saw the successful boycotting of White businesses that discriminated against black people, and chain stores reportedly lost $49,225 in sales tax revenues.

Unlike the Freedom Riders, Friendship Nine, and Little Rock Nine, the Tougaloo Nine are not as well-known historically. Sammy Bradford, one of the Tougaloo Nine, said on the occasion of the read-in anniversary: “It seems that everybody is being celebrated and praised for their fine work except the very people who launched the civil rights movement against some of the greatest odds ever faced by man or beast. I’m not saying that the Tougaloo Nine should be rolled out like world-conquering heroes in a ticker-tape parade every year, but they should at least be acknowledged, along with many others, whenever a purported celebration of civil rights activities in Mississippi takes place.”

The 1961 efforts of the Tougaloo Nine to desegregate the Jackson Municipal Library were commemorated today with a Mississippi Freedom Trail marker. Seven of the surviving students attended the ceremony: Ethel Sawyer Adolphe, Meredith Anding, Jr., James “Sammy” Bradford, Alfred Cook, Geraldine Edwards Hollis, Albert Lassiter, and Janice Jackson Vails. The Tougaloo College alumni also got to preview exhibits inside the Mississippi Civil Rights

On Aug. 17, 2007, members of the Tougaloo Nine unveiled the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker recognizing them for their peaceful sit-in at the Jackson Municipal Library in Jackson, Miss. The nine people arrested on March 27, 1961, were students at the private Tougaloo College.

ROGELIO V. SOLIS/AP

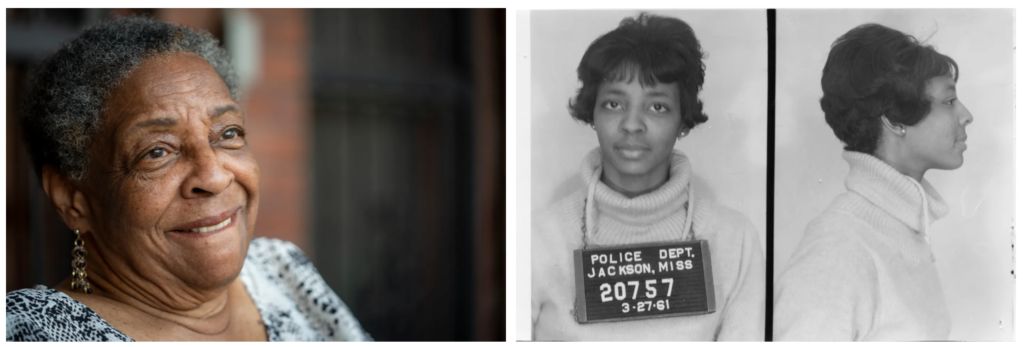

Sawyer, 81, has no regrets. “Not a one,” she said. “I‘d do it again. I’d do it 10 times.”

“Police arrived quickly at the Jackson Municipal Library that morning. They ordered the students scattered at different tables to go across town to the colored library.

“This is an unlawful assembly, and you’re ordered to disperse, to leave,” the sheriff commanded.

The students kept still. They were arrested for “breach of the peace” and paraded past the crowd outside shouting at them and cursing them.

Flanked by police, Sawyer threw her head back, tilting her chin toward the sky, snubbing her taunters.

“The heck with you,” she thought.“

Ethel Sawyer Adolphe is one of the Tougaloo Nine students who demonstrated at Jackson Municipal Library on March 27, 1961. Police booked Sawyer for entering the all-white library in Jackson, Miss.

JASPER COLT, USA TODAY; MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY