Remembering Glenda Dickerson Re/membering Aunt Jemima:

A Menstrual Show

“Contemporary Black women are all but invisible in a popular culture and society which fears and loathes us unless we can be fitted comfortably into a recognizable stereotype: the Mammy, the Sapphire, the Jezebel, the Tragic Mulatta.”

From Playwright’s notes to “Re/Membering Aunt Jemima: A Menstrual Show by Breena Clarke and Glenda Dickerson included in “Colored Contradictions: An Anthology of Contemporary African-American Plays”, edited by Harry J. Elam Jr. and Robert Alexander, 1996.

Glenda Dickerson (1945 – 2012) and Breena Clarke pose with the universally despised, disreputable, demeaning stereotype, Aunt Jemima, the most infamous colored woman in the world. They are holding a somewhat valuable collectible McCoy Aunt Jemima cookie jar.

I wrote, “Re/Membering Aunt Jemima: A Menstrual Show” with the late, Glenda Dickerson (1945 – 2012) in the very early 1990’s. Glenda Dickerson and I seized on the iconography of Aunt Jemima, the oldest and most well-known advertising symbol in American material culture because she embodied all of the elements that we’d been taught to despise. We decided to use a disreputable form of popular entertainment – the Minstrel Show, an enduring theatrical invention of Northern imitators of Southern plantation performers – as our theatrical stylistic framework. Minstrelsy, developed in the 19th century and was organized as a three-part show, was a style based solely on exploiting gross racial stereotypes for laughs. We chose this convention as the basic framework for our look at Aunt Jemima. For a fuller discussion of the Minstrel Show, see “African American Theater: A Cultural Companion by Glenda Dickerson. http://bit.ly/1Mzwk7k

The playwrights choose to use the minstrel format and its most potent device – innovative wordplay such as malapropisms, puns, conundrums, and double entendre – in an attempt to write Black female identity into existence on the world stage. Thus, this postmodern Menstrual Show is created to provide a “place” or context for the latter-day African-American woman performer.

“In the US, the minstrel shows began with working-class white men dressing up as plantation slaves. White performers blackened their faces with burnt cork or greasepaint and performed songs and skits that mocked enslaved Africans.” [1]

[1] African American Theater: A Cultural Companion by Glenda Dickerson, 2008

Eleanor Bumpurs

The climax of “Re/Membering Aunt Jemima: A Menstrual Show is the death of Aunt Jemima in her Eleanor Bumpurs persona at the hands of a policeman. Eleanor Bumpurs, a mentally ill, arthritic and elderly African American woman was shot and killed on October 29, 1984 by New York City policeman, Stephen Sullivan. Eleanor Bumpurs, became, in our play, Aunt Jemima’s doppleganger. Tawanna Brawley, Anita Hill and others became her daughters.

The police were present that day in Bumpurs’ Bronx apartment to enforce a city ordered eviction of Bumpurs for failure to pay four months past due on her monthly rent of $98.65. Housing authority workers told police that Bumpurs was emotionally disturbed, had threatened to throw boiling lye and was using a knife to resist eviction. When Bumpurs refused to open the door, police broke in. In the struggle to subdue her, one officer shot Bumpurs twice with a 12-gauge shotgun.They killed her.

Glenda Dickerson and I started writing “Re/Membering Aunt Jemima: A Menstrual Show” by pondering the imagistic details of the Bumpurs case. Why hadn’t this Sullivan guy – the cop who shot her – seen her as we saw her, as her family saw her and as the man across the hall who said he was looking out his peephole and saw her naked body in the hallway for a long time saw her? No respect — no respect for the black body naked and dead and on display. Hours later they covered her with a sheet before taking her away to the morgue, but left part of her blasted finger on the floor for her daughter to find.

RE/MEMBERING AUNT JEMIMA: A MENSTRUAL SHOW is included in “Contemporary Plays by Women of Color, edited by Kathy Perkins and Roberta Uno and “Colored Contradictions, edited by Harry Elam, Jr. and Robert Alexander.

for more information on Breena Clarke’s books: www.BreenaClarke.com

Dickerson is co-author of Re/membering Aunt Jemima: A Menstrual Show, which is published in Colored Contradictions: an anthology of contemporary African American plays (Plume). Her recent essays include “Let the People See What I’ve Seen: In Praise of Mamie Till” and “Katrina: acting black/playing blackness” in Theatre Journal.

Dickerson was currently working on Anabel’s Brush, an oral history of Georgia Sea Island descendants of African slaves; and a book The Saga of Lily Overstreet: Rhodessa Jones and the spectacular review.

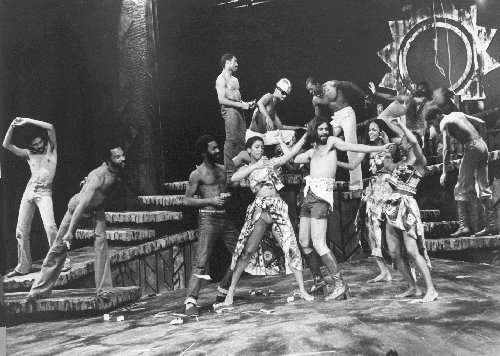

Jesus Christ, Lawd Today

A musical “miracle play” directed and adapted by Glenda Dickerson in 1971.

- Communal Storytelling: Staged at the African-American Theatre, it reinterpreted biblical narratives through the lens of urban Black experiences and folklore.

- Cultural Style: The play utilized gospel music, African American vernacular, and a “womanist” perspective to prioritize authentic representation over mainstream theatrical norms.

- Creative Team: It was one of several influential collaborations between Dickerson and director/choreographer Mike Malone, who together helped shape the D.C. theater scene and influenced future stars.

- Legacy: The production helped launch the careers of numerous actors and dancers, including Debbie Allen and Phylicia Rashad, who were part of the ensemble of artists Dickerson mentored during this era.

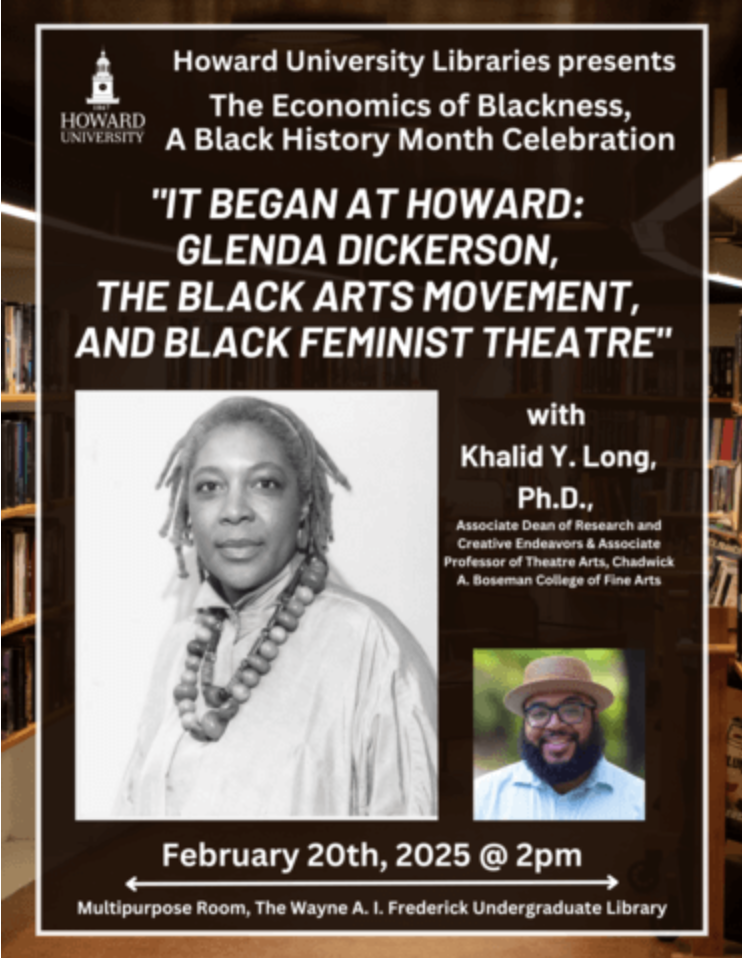

Dr Khalid Yaya Long Presents: An Architect of Black Feminist Theatre

“Sprang into Visibility”: Glenda Dickerson, Eel Catching in Setauket, and Oral History as Community Theatre

✨FREE ONLINE LECTURE- ZOOM✨

⭐Monday, February 17th, 2025 – 7:00 pm⭐

Dr. Khalid Y. Long, Associate Dean of Research and Creative Endeavors and Associate Professor of Theatre Arts at Howard University, will deliver a captivating lecture exploring the life and works of Black feminist theatre artist Glenda Dickerson (1945-2012).

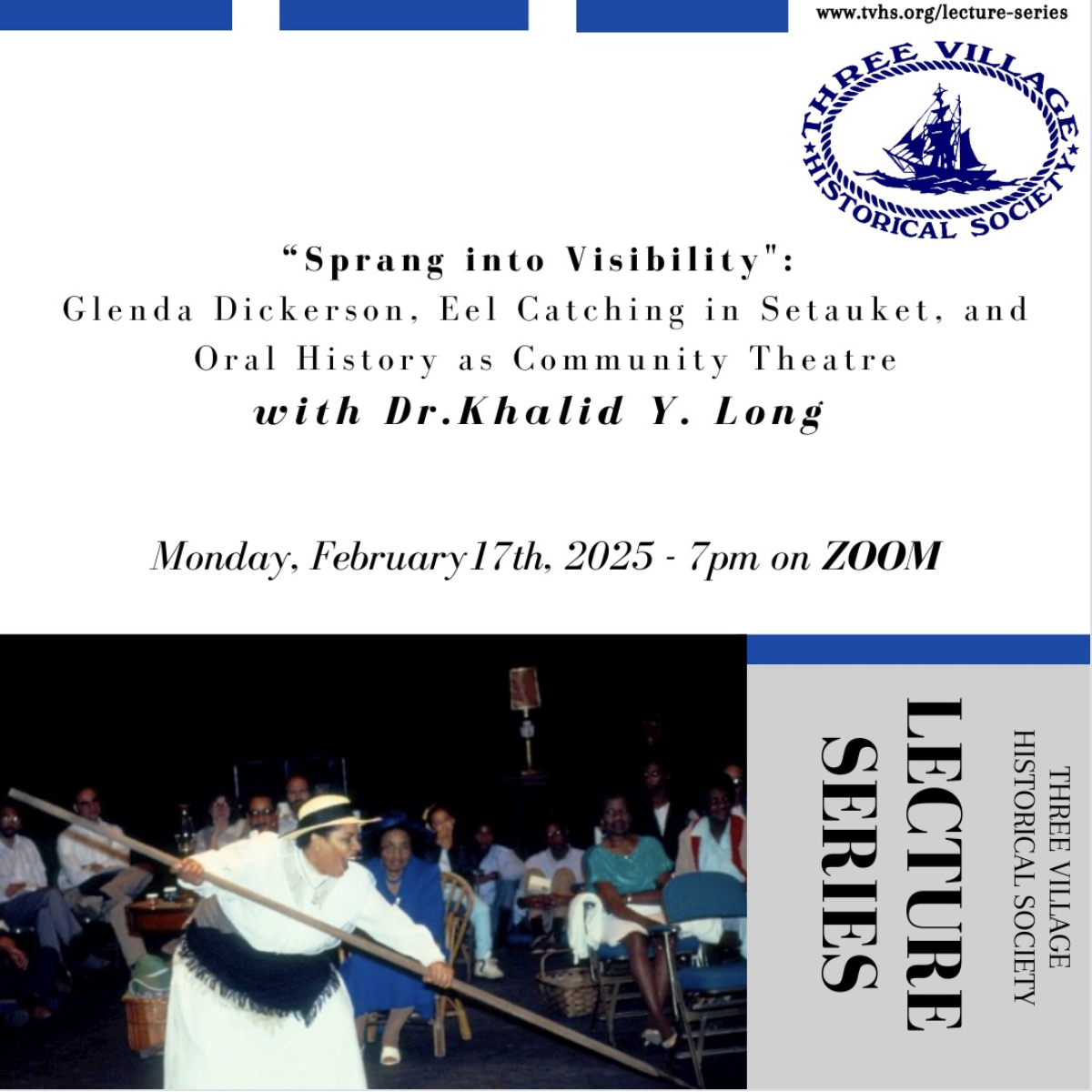

The talk will center on her 1988 project, “Eel Catching in Setauket: A Living Portrait of the Christian Avenue Community“, and examine how Dickerson utilized oral history as a tool for community theatre, bringing marginalized voices and stories into the spotlight.

Dr. Long, an expert in African American/Black diasporic theatre, will also share insights from his extensive research and upcoming book, “An Architect of Black Feminist Theatre: Glenda Dickerson, Transnational Feminism, and The Kitchen Prayer Series“.