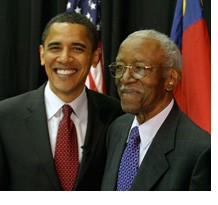

“I think this will be in a class by itself.” Obama’s campaign”is the most radical, far-reaching, significant [undertaking] by any individual or group in our history,” he said.”This strikes at the very heart of national ideology on race and the political patterns of this country’s history.”

“I think this will be in a class by itself.” Obama’s campaign”is the most radical, far-reaching, significant [undertaking] by any individual or group in our history,” he said.”This strikes at the very heart of national ideology on race and the political patterns of this country’s history.”

Adapted from John Hope Franklin’s author biography from his memoir”Mirror to America” Published in November 2005 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Excerpt from Mirror to America

No Crystal Stair

“Living in a world restricted by laws defining race, as well as creating obstacles, disadvantages, and even superstitions regarding race challenged my capacities for survival. For ninety years I have witnessed countless men and women likewise meet this challenge. Some bested it; some did not; many had to settle for any accommodation they could. I became a student and eventually a scholar. And it was armed with the tools of scholarship that I strove to dismantle those laws, level those obstacles and disadvantages, and replace superstitions with humane dignity. Along with much else, the habits of scholarship granted me something many of my similarly striving contemporaries did not have. I knew or should say know, what we are up against.

Slavery was a principal centerpiece of the New World Order that set standards of conduct including complicated patterns of relationships. These lasted not merely until emancipation but after Reconstruction and on into the twentieth century. Many of them were still very much in place when beginning in the late 1950s, the sit-ins, marches, and the black revolution began a successful onslaught on some of the antediluvian practices that had become a part of the very fabric of society in the New World and American society in particular.

Born in 1915, I grew up in a racial climate that was stifling to my senses and damaging to my emotional health and social well-being. Society at that time presented a challenge to the strongest adult, and to a child, it was not merely difficult but cruel. I watched my mother and father, who surely numbered among the former, daily meet that challenge; I and my three siblings felt equally that cruelty. And it was no more possible to escape that environment of racist barbarism than one today can escape the industrial gases that pollute the atmosphere.

This climate touched me at every stage of my life. I was forcibly removed from a train at the age of six for having accidentally taken a seat in the”white people’s coach.” I was the unhappy victim, also at age six, of a race riot that kept the family divided for more than four years. I endured the very strict segregation laws and practices in Tulsa, Oklahoma. I was rejected as a guide through busy downtown Tulsa traffic by a blind white woman when she discovered that the twelve-year-old at her side was black. I underwent the harrowing experience as a sixteen-year-old college freshman of being denounced in the most insulting terms for having the temerity to suggest to a white ticket seller a convenient way make a change. More harrowing yet was the crowd of rural white men who confronted and then nominated me as a possible Mississippi lynching victim when I was nineteen. I was refused service while on a date as a Harvard University graduate student at age twenty-one. Racism in the navy turned my effort to volunteer during World War II into a demeaning embarrassment, such that at a time when the United States was ostensibly fighting for the Four Freedoms I struggled to evade the draft. I was called a”Harvard nigger” at age forty. At age forty-five, because of race, New York banks denied me a loan to purchase a home. At age sixty I was ordered to serve as a porter for a white person in a New York hotel, at age eighty to hang up a White guest’s coat at a Washington club where I was not an employee but a member.