The Civil Radical Wars

of the Black American Soldier

by DALE RICARDO SHIELDS

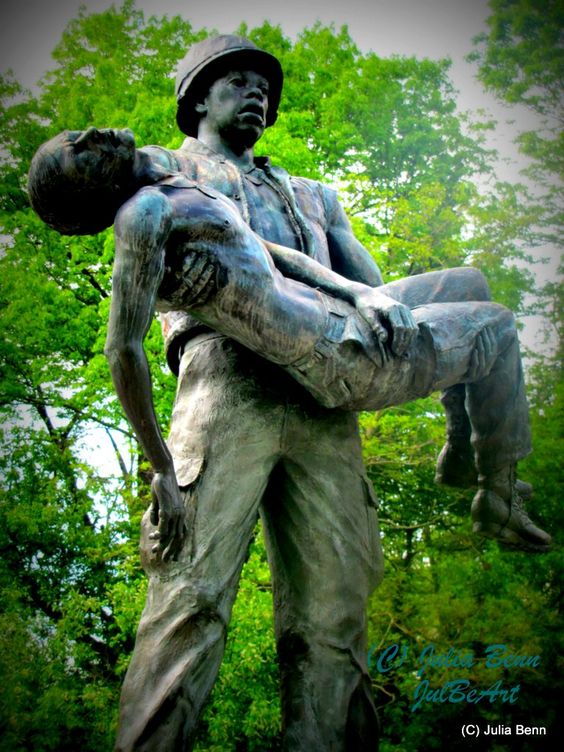

The African-American Medal of Honor Statue, Wilmington, DE pays homage to African-American veterans.

“Throughout America’s history, from the Battle of Lexington to the Battle of Fallujah, Black Soldiers have honorably answered the call to duty, serving with great valor and distinction in America’s armed forces.

The Army story cannot be told without reflecting on the historical achievements made by Black Americans and preserving those memories. Black Americans have served and sacrificed in every conflict in our nation’s history, with more than 245 years of honorable service.

Black Americans, who have defended our nation since the Revolutionary War, have built a legacy of courage and professionalism by serving the U.S. Army with great honor and distinction, inspiring generations to come – we recognize and honor that legacy always.”

“FOR MORE THAN 200 YEARS, AFRICAN AMERICANS HAVE PARTICIPATED IN EVERY CONFLICT IN UNITED STATES HISTORY. THEY HAVE NOT ONLY BRAVELY FOUGHT THE COMMON ENEMIES OF THE UNITED STATES, BUT HAVE ALSO HAD TO CONFRONT THE INDIVIDUAL AND INSTITUTIONAL RACISM OF THEIR COUNTRYMEN.”

— Retired Lt. Col. Michael Lee Lanning, – “The African-American Soldier: From Crispus Attucks to Colin Powell”

“Americans appropriately celebrate the valor, bravery, and courage of the men and women who have fought and risked their lives for this country. But the history of racial terrorism and violence endured by thousands of African American veterans remains unacknowledged.” – Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans

America’s Black Civil War soldiers — CNN

“The end of the Civil War ushered in a new era of racial terror lynchings and violence directed at Black people in America that was designed to sustain a system of White supremacy and hierarchy, one whose brutal repercussions have not been fully acknowledged in this country.

No one was more at risk of experiencing targeted violence than Black veterans who had proven their valor and courage as soldiers during the Civil War, World War I, and World War II. Military service sparked dreams of racial equality for generations of African Americans, but rather than being welcomed home and honored for their service, many Black veterans were targeted for mistreatment, violence, and murder during the lynching era due to their race and military experience.

Between the end of Reconstruction and the years following World War II, the experience of military service for African Americans often inflamed an attitude of defiant resistance to the status quo that could prove deadly in a society where racial subordination was violently enforced. Throughout the American South, parts of the Midwest, and the Northeast, dozens of Black veterans died at the hands of mobs and persons acting under the color of official authority; many survived near-lynchings; and thousands suffered severe assaults and social humiliation.

The disproportionate abuse and assaults against Black veterans have never been fully acknowledged. Targeting Black Veterans highlights the particular challenges endured by Black veterans in the hope that our nation can better confront the legacy of this violence and terror. No community is more deserving of recognition and acknowledgment than those Black men and women veterans who bravely risked their lives to defend this country’s freedom, only to have their freedom denied and threatened because of racial bigotry.

Targeting Black Veterans builds on our Lynching in America report, which documents over 4000 lynchings of African Americans between 1877 and 1950. Lynching in America explores how racial terrorism profoundly shaped the nation’s demographics and reinforced a myth of racial inferiority and a legacy of racial inequality that is readily apparent in our criminal justice system today.

Research on mass violence, trauma, and transitional justice underscores the urgent need to engage in public conversations about racial history that begin a process of truth and reconciliation in this country. Documenting the atrocities of lynching and targeted racial violence is vital to understanding the incongruity of our country’s professed ideals of freedom and democracy while tolerating ongoing violence against people of color within our borders.”

https://eji.org/reports/targeting-black-veterans/

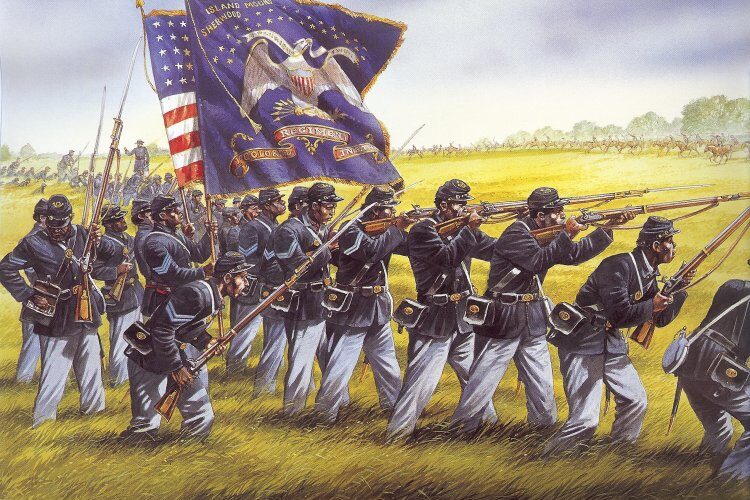

“United States Colored Troops (USCT) were Union Army regiments during the American Civil War that primarily comprised African Americans, with soldiers from other ethnic groups also serving in USCT units. Established in response to a demand for more units from Union Army commanders, by the end of the war in 1865 USCT regiments, which numbered 175 in total, constituted about one-tenth of the manpower of the army. Approximately 20% of USCT soldiers were killed in action or died of disease and other causes, a rate about 35% higher than that of white Union troops. Numerous USCT soldiers fought with distinction, with 16 receiving the Medal of Honor. The USCT regiments were precursors to the Buffalo Soldier units which fought in the American Indian Wars.”

African Americans have always been involved in United States military service since its inception despite official policies of racial segregation and discrimination.

Formation

The United States War Department issued General Order Number 143 on May 22, 1863, establishing the Bureau of Colored Troops to facilitate the recruitment of African-American soldiers to fight for the Union Army. Regiments, including infantry, cavalry, engineers, light artillery, and heavy artillery units were recruited from all states of the Union. Approximately 175 regiments comprising more than 178,000 free blacks and freedmen served during the last two years of the war. Their service bolstered the Union war effort at a critical time. By the war’s end, the men of the USCT made up nearly one-tenth of all Union troops. The Regular Army troops made up about 3% of total US Troops who fought in the war.

Soldiers Of The 33rd United States Colored Troops

The 33rd was oganized January 31, 1863 or February 8, 1864, as 1st South Carolina Volunteers Colored Infantry. Attached to U. S. Forces, Port Royal Island, South Carolina, 10th Corps, Dept. of the South, to April, 1864. Mustered out January 31, 1866

“No officer in this regiment now doubts that the key to the successful prosecution of this war lies in the unlimited employment of Black troops.

The 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Colored) was a Union Army regiment during the American Civil War, formed by General Rufus Saxton. It was composed of escaped slaves from South Carolina and Florida. It was one of the first Black regiments in the Union Army.

Members of the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment 1863

Public Domain

John Hines, formerly enslaved and cook of Company K, 15th Penn. Cavalry

The USCT suffered 2,751 combat casualties during the war, and 68,178 losses from all causes. Disease caused the most fatalities for all troops, both Black and White. In the last year and a half and from all reported casualties, approximately 20% of all African Americans enrolled in the military lost their lives. Notably, their mortality rate was significantly higher than White soldiers:

“[We] find, according to the revised official data, that of the slightly over two millions troops in the United States Volunteers, over 316,000 died (from all causes), or 15.2%. Of the 67,000 Regular Army (White) troops, 8.6%, or not quite 6,000, died. Of the approximately 180,000 United States Colored Troops, however, over 36,000 died, or 20.5%. In other words, the mortality rate amongst the United States Colored Troops in the Civil War was thirty-five percent greater than that among other troops, notwithstanding the fact that the former were not enrolled until some eighteen months after the fighting began.”

— Herbert Aptheker American Civil War military unit / From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

Frederick Douglass

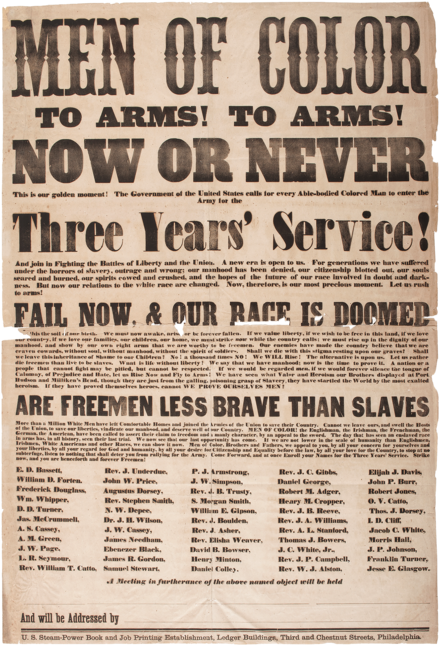

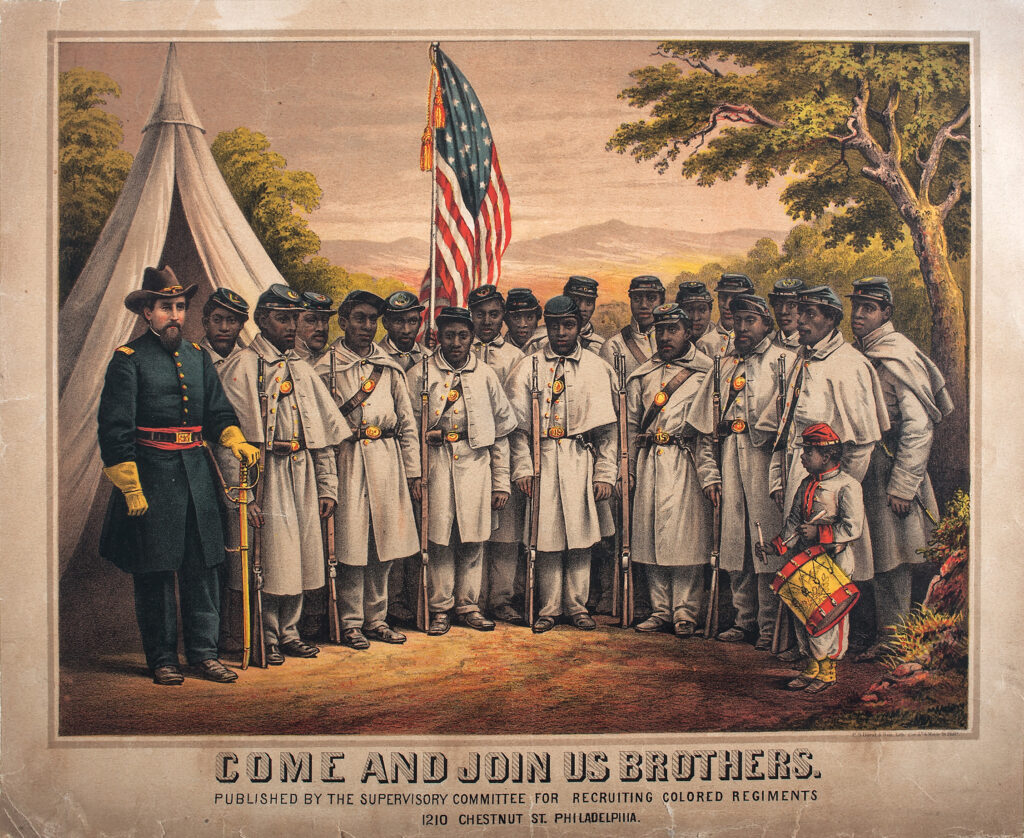

“A range of emotions from uncertainty to truculence plays on the faces of these Philadelphia recruits in early 1864. Their regiment, the 25th U.S. Colored Infantry, sailed soon afterward for the Gulf of Mexico, where it formed part of the garrison of New Orleans, and later of Pensacola. (Army)“

“The issues of emancipation and military service were intertwined from the onset of the Civil War. News from Fort Sumter set off a rush by free Black men to enlist in U.S. military units. They were turned away, however, because a Federal law dating from 1792 barred Negroes from bearing arms for the U.S. army (although they had served in the American Revolution and the War of 1812). In Boston disappointed would-be volunteers met and passed a resolution requesting that the Government modify its laws to permit their enlistment.

The Lincoln administration wrestled with the idea of authorizing the recruitment of Black troops, concerned that such a move would prompt the border states to secede. When Gen. John C. Frémont (photo citation: 111-B-3756) in Missouri and Gen. David Hunter (photo citation: 111-B-3580) in South Carolina issued proclamations that emancipated slaves in their military regions and permitted them to enlist, their superiors sternly revoked their orders. By mid-1862, however, the escalating number of former Slaves (contrabands), the declining number of white volunteers, and the increasingly pressing personnel needs of the Union Army pushed the Government into reconsidering the ban.

1st. Carolina Volunteers Infantry 1862

by Don Troiani

First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry was the first officially recognized black unit of the Union Army during the Civil War. It was quietly authorized by President Abraham Lincoln and organized in August of 1862. The regiment reached its full complement of 1,000 men and was mustered in during November of that year.

As a result, on July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, freeing slaves who had masters in the Confederate Army. Two days later, slavery was abolished in the territories of the United States, and on July 22 President Lincoln (photo citation: 111-B-2323) presented the preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation to his Cabinet. After the Union Army turned back Lee’s first invasion of the North at Antietam, MD, and the Emancipation Proclamation was subsequently announced, Black recruitment was pursued in earnest. Volunteers from South Carolina, Tennessee, and Massachusetts filled the first authorized Black regiments. Recruitment was slow until black leaders such as Frederick Douglass (photo citation: 200-FL-22) encouraged Black men to become soldiers to ensure eventual full citizenship. (Two of Douglass’s sons contributed to the war effort.) Volunteers began to respond, and in May 1863 the Government established the Bureau of Colored Troops to manage the burgeoning numbers of Black soldiers.

By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 Black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 Black soldiers died throughout the war—30,000 of infection or disease. Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well. Black carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters also contributed to the war cause. There were nearly 80 Black commissioned officers. Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman (photo citation: 200-HN-PIO-1), who scouted for the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers.

Because of prejudice against them, Black units were not used in combat as extensively as they might have been. Nevertheless, the soldiers served with distinction in several battles. Black infantrymen fought gallantly at Milliken’s Bend, LA; Port Hudson, LA; Petersburg, VA; and Nashville, TN. The July 1863 assault on Fort Wagner, SC, in which the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers lost two-thirds of their officers and half of their troops, was memorably dramatized in the film Glory. By the war’s end, 16 Black soldiers had been awarded the Medal of Honor for their valor.

SANKOFA DESIGNS

July 16, 1863: The 54th Massachusetts Infantry had its baptism of fire at the Battle of Grimball’s Landing on James Island, South Carolina during the Civil War.

During the battle the 10th Connecticut Infantry, a White regiment, was in an exposed position and in jeopardy of being cut off by Rebel forces. The Confederate efforts to get around them were checked by the 54th Massachusetts, who rebuffed a series of attacks while the 10th Connecticut was withdrawn.

The 54th suffered 43 casualties, with 14 killed, 17 wounded, and 12 others lost to capture, but the 10th Connecticut was saved from annihilation. By all accounts, the men of the 54th behaved splendidly; there was now no doubt that Black men could — and would — fight well.

Colonel Robert Gould Shaw would write to his wife the next day:

“You don’t know what a fortunate day this has been for me and for all of us, accepting some poor fellows who were killed and wounded. We have at last fought alongside white troops… General Terry sent me word that he was highly gratified with the behavior of my men, and the officers and privates of other regiments praise us very much. All this is very gratifying to us personally, and a fine thing for the colored troops. It is the first time they have been associated with White soldiers, this side of the Mississippi.”

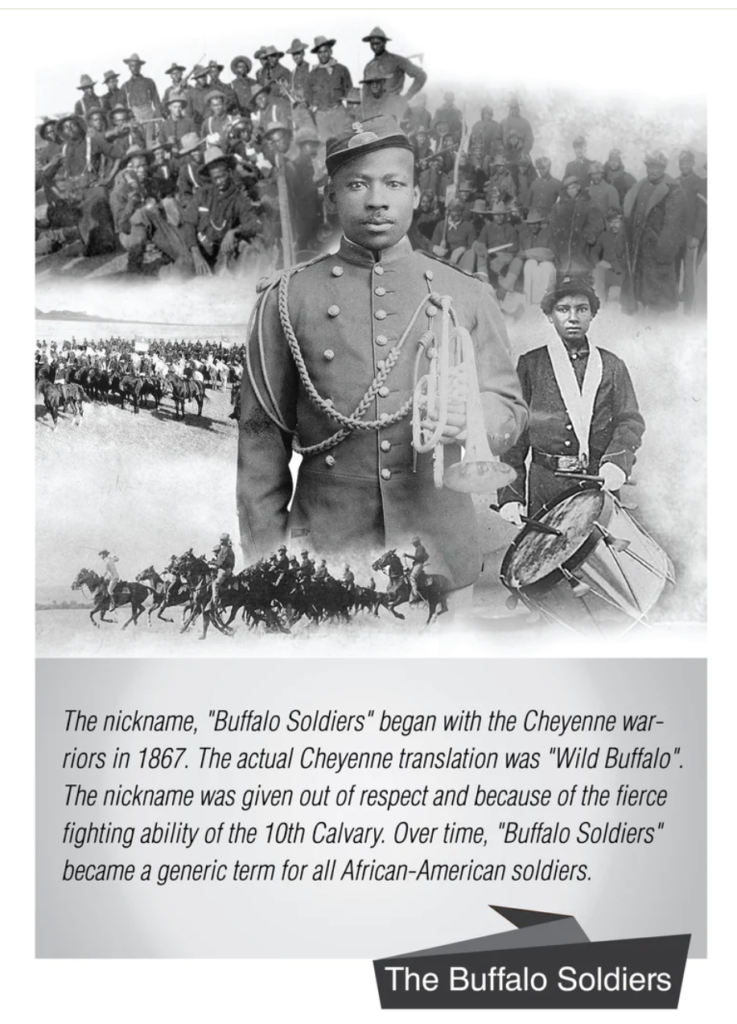

Buffalo Soldiers.

Those members of the 9th and 10th Calvary

remembered for their fierce fighting ability.

In addition to the perils of war faced by all Civil War soldiers, Black soldiers faced additional problems stemming from racial prejudice. Racial discrimination was prevalent even in the North, and discriminatory practices permeated the U.S. military. Segregated units were formed with Black enlisted men and typically commanded by White officers and black noncommissioned officers. The 54th Massachusetts was commanded by Robert Shaw and the 1st South Carolina by Thomas Wentworth Higginson—both White. Black soldiers were initially paid $10 per month from which $3 was automatically deducted for clothing, resulting in a net pay of $7. In contrast, White soldiers received $13 per month from which no clothing allowance was drawn. In June 1864 Congress granted equal pay to the U.S. Colored Troops and made the action retroactive. Black soldiers received the same rations and supplies. In addition, they received comparable medical care.

Civil War Soldiers in front of a house 1860s

Public Domain

The Black troops, however, faced greater peril than White troops when captured by the Confederate Army. In 1863 the Confederate Congress threatened to punish severely officers of Black troops and to enslave Black soldiers. As a result, President Lincoln issued General Order 233, threatening reprisal on Confederate prisoners of war (POWs) for any mistreatment of Black troops. Although the threat generally restrained the Confederates, Black captives were typically treated more harshly than White captives. In perhaps the most heinous known example of abuse, Confederate soldiers shot to death Black Union soldiers captured at the Fort Pillow, TN, engagement of 1864. Confederate General Nathan B. Forrest witnessed the massacre and did nothing to stop it.

22nd United States Colored Infantry

Active January 10, 1864 – October 16, 1865

Country United States

Allegiance Union

Branch Infantry

Engagements Siege of Petersburg

Second Battle of Deep Bottom

Battle of Chaffin’s Farm

Battle of Fair Oaks & Darbytown Road

The document featured in this article is a recruiting poster directed at Black men during the Civil War. It refers to efforts by the Lincoln administration to provide equal pay for Black soldiers and equal protection for black POWs. The original poster is located in the Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, the 1780s–1917, Record Group 94.”

Article Citation

Freeman, Elsie, Wynell Burroughs Schamel, and Jean West. “The Fight for Equal Rights: A Recruiting Poster for Black Soldiers in the Civil War.” Social Education 56, 2 (February 1992): 118-120. [Revised and updated in 1999 by Budge Weidman.]

*

The Apache Scouts

This 1885 boudoir card of the US Army’s 10th Regiment is the only known example to show Apache scouts side-by-side African American Buffalo Soldiers.

Public Domain

“The Apache Scouts were part of the United States Army Indian Scouts. Most of their service was during the Apache Wars, between 1849 and 1886, though the last scout retired in 1947. The Apache scouts were the eyes and ears of the United States military and sometimes the cultural translators for the various Apache bands and the Americans. Apache scouts also served in the Navajo War, the Yavapai War, the Mexican Border War and they saw stateside duty during World War II.” – Wikipedia®

“There has been a great deal written about Apache scouts, both as part of United States Army reports from the field and more colorful accounts written after the events by non-Apaches in newspapers and books. Men such as Al Sieber and TomHorn weree sometimes the commanding officers of small groups of Apache Scouts. As was the custom in the United States military, scouts were generally enlisted with Anglo nicknames or single names. Many Apache Scouts received citations for bravery.” – Wikipedia®

From 1867 to the early 1890s, these regiments served at a variety of posts in the Southwestern United States and the Great Plains regions. They participated in most of the military campaigns in these areas and earned a distinguished record. Thirteen enlisted men and six officers from these four regiments earned the Medal of Honor during the Indian Wars. In addition to the military campaigns, the Buffalo Soldiers served a variety of roles along the frontier, from building roads to escorting the U.S. mail. On April 17, 1875, regimental headquarters for the 10th Cavalry was transferred to Fort Concho, Texas. Companies actually arrived at Fort Concho in May 1873. The 9th Cavalry was headquartered at Fort Union from 1875 to 1881. At various times from 1873 through 1885, Fort Concho housed 9th Cavalry companies A–F, K, and M, 10th Cavalry companies A, D–G, I, L, and M, 24th Infantry companies D–G, and K, and 25th Infantry companies G and K.

From 1879 to 1881, portions of all four of the Buffalo Soldier regiments were in New Mexico pursuing Victorio and Nana and their Apache warriors in Victorio’s War. The 9th Cavalry spent the winter of 1890 to 1891 guarding the Pine Ridge Reservation during the events of the Ghost Dance War and the Wounded Knee Massacre. Cavalry regiments were also used to remove Sooners (whites), who were squatting (illegally occupying) native lands in the late 1880s and early 1890s. – Wikipedia®

Buffalo soldiers fought in the last engagement of the Indian Wars, the small Battle of Bear Valley in southern Arizona which occurred in 1918 between U.S. cavalry and Yaqui natives. In total, 23 Buffalo Soldiers received the Medal of Honor during the Indian Wars