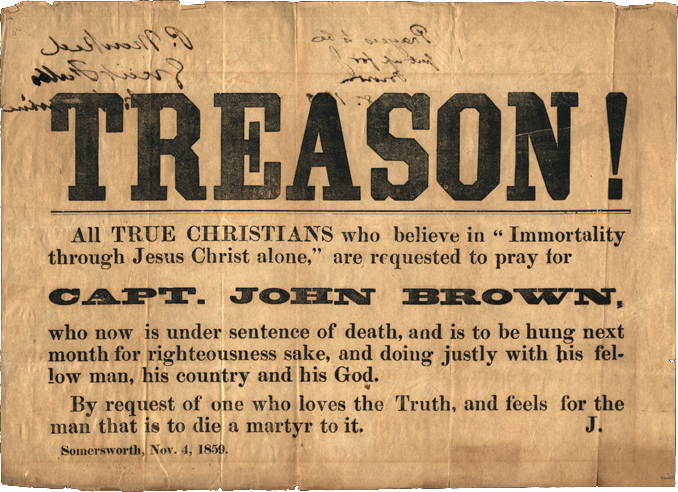

John Brown

In October of 1859, a group of rebel slaves led by John Brown tried to seize control of arms at the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia.

“John Brown’s career for the last six weeks of his life was meteor-like, flashing through the darkness in which we live. I know of nothing so miraculous in our history.”

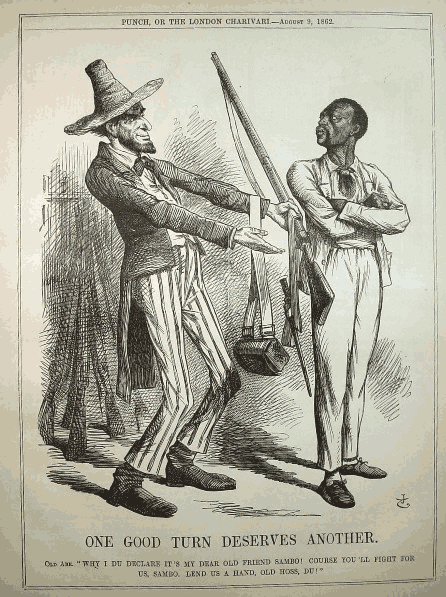

Though it failed, this event brought relations between the North and South to a breaking point. In 1860, Abraham Lincoln became the 14th president of the United States. Lincoln was heavily ill-favored among many southern states. The South saw this as the last straw and finally began to successfully break away from the Union. They formed the Confederate States of America and appointed Jefferson Davis as their president. He would be the first and only president of the group. The war began in 1861 with an attack by Confederate troops on Union forces provisioning Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Immediately Abolitionists saw the outbreak of war as a cause of slavery. This led to many Black men eager to strike a blow in the name of freedom by offering their service. Militias began to form separate from the Federal Army and began drilling outside of several major cities. These were not the only people who believed that African Americans should join the war. General Benjamin F. Butler, commander of Fort Monroe, saw that if the Union returned escaped slaves back to the South, then they would be strengthening the South against the Union. He instead put runaway slaves to work for the Union as laborers. Butler also invoked the idea that since slaves were seen as property, any slaves found in the North would be considered contraband of war.

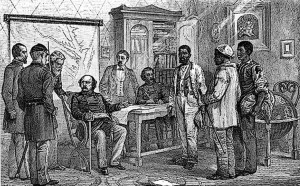

This period print shows Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler interviewed the three runaway slaves — traditionally identified as Shepard Mallory, Frank Baker, and James Townsend, who sparked his landmark May 24, 1861 decision to give such slaves refuge as “contraband of war.”

This led to the First and Second Confiscation Act which eventually freed escaped slaves once they were in the North (Creating Black Americans). Despite this, the Lincoln administration refused any entry of Black American soldiers into the war. They stated that the war was about the reunification of the “Union” and not about “Slavery.” Many Northerners also claimed the war as a “White Man’s War” and thought that having to serve alongside Black men would discourage the other soldiers. In addition to this many in the north believed the war would be quick, but by 1862 it was clear that the war would take a lot longer and require much more manpower and sacrifice (Battle Cry of Freedom).

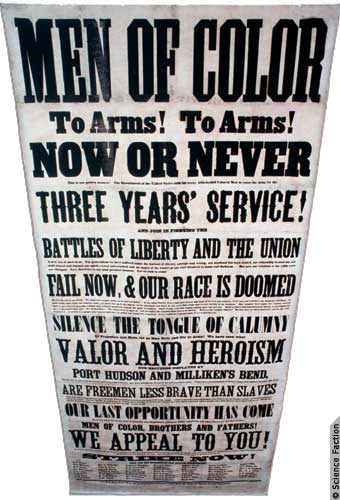

With the following of the Second Emancipation Proclamation, Black men everywhere began to be recruited, and colored regiments were formed.

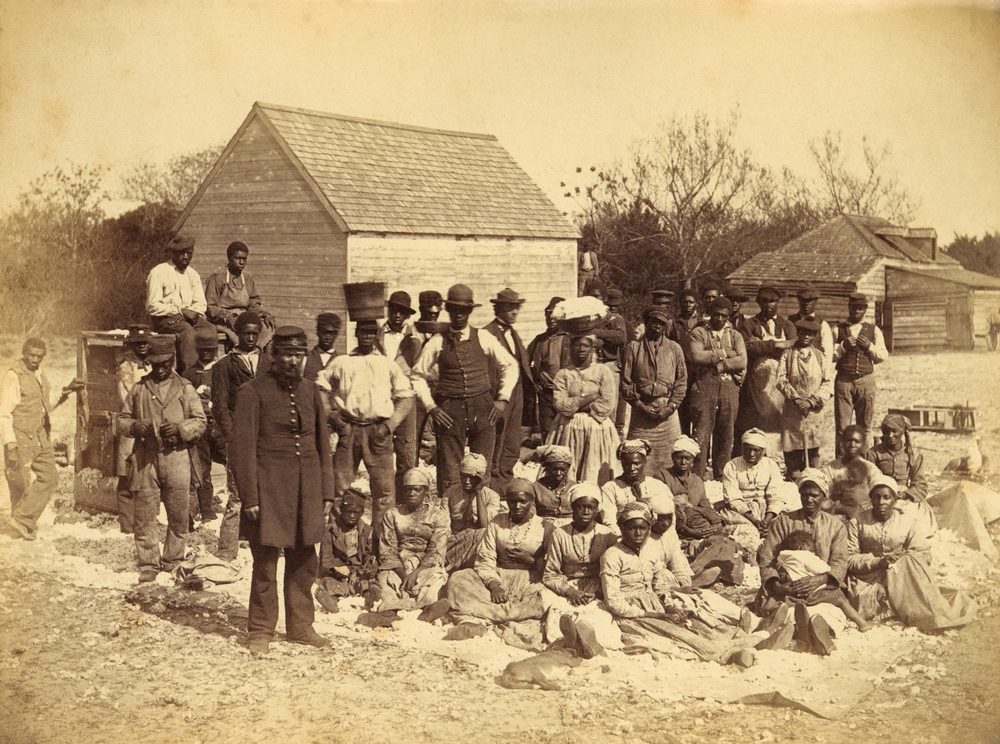

A Union soldier stands with African Americans on a plantation, Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, 1862. (Shutterstock)