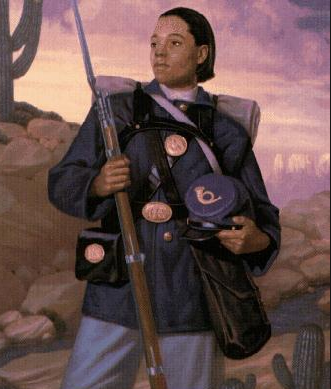

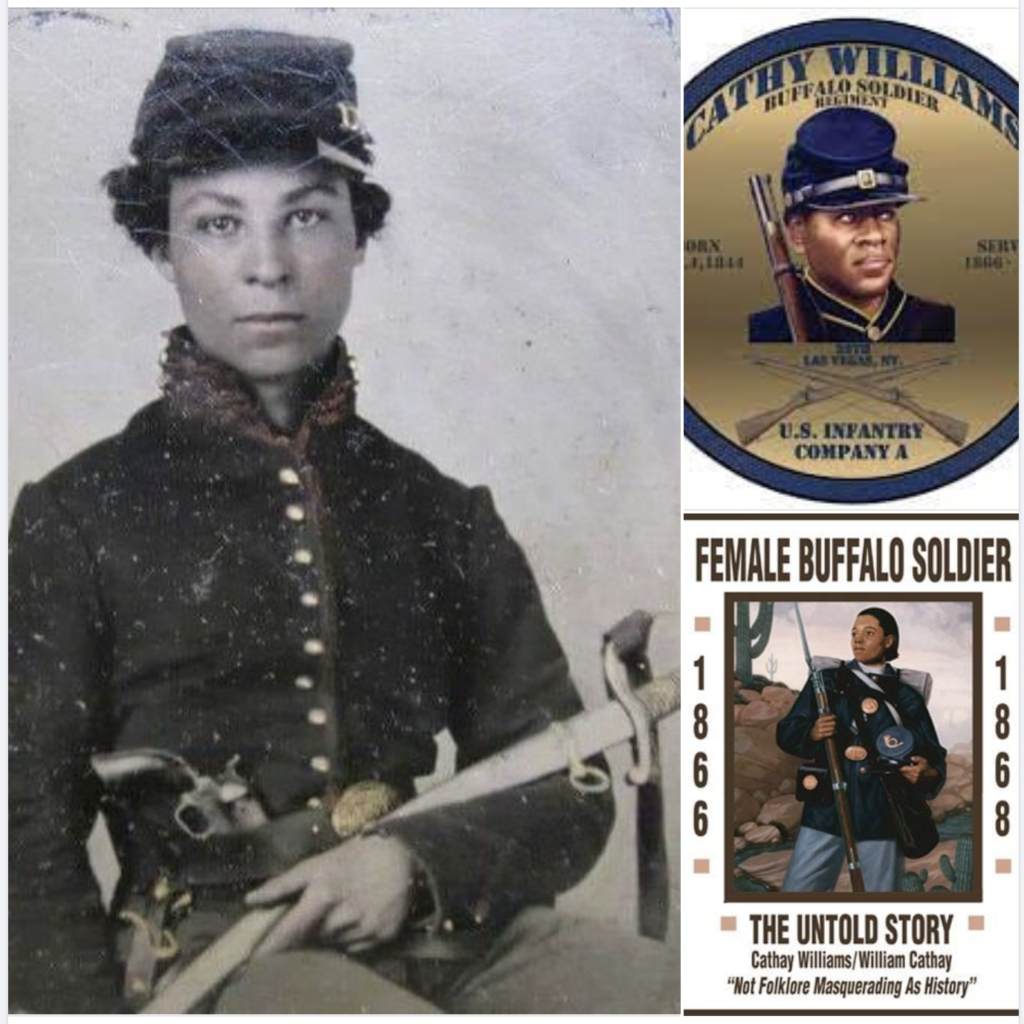

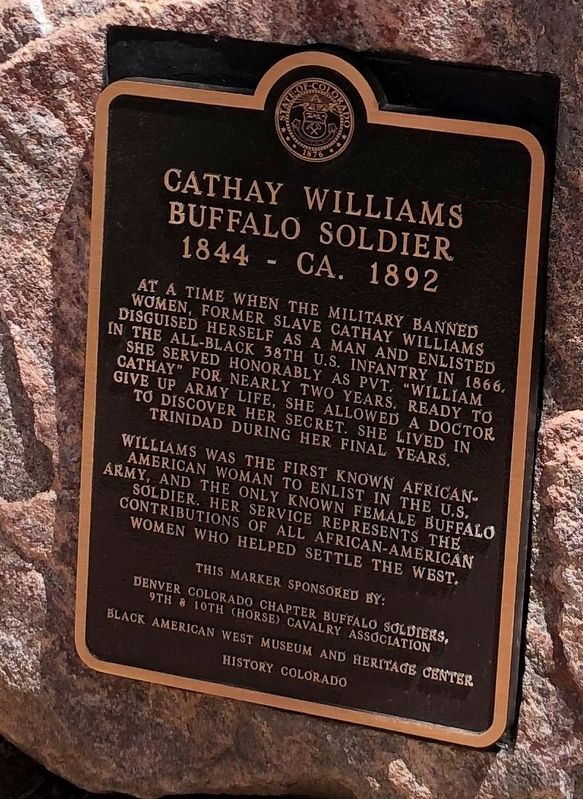

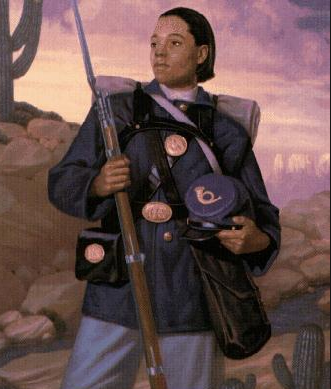

Cathay Williams Was the Army’s Only Female Buffalo Soldier

and the First Black Female Enlistee

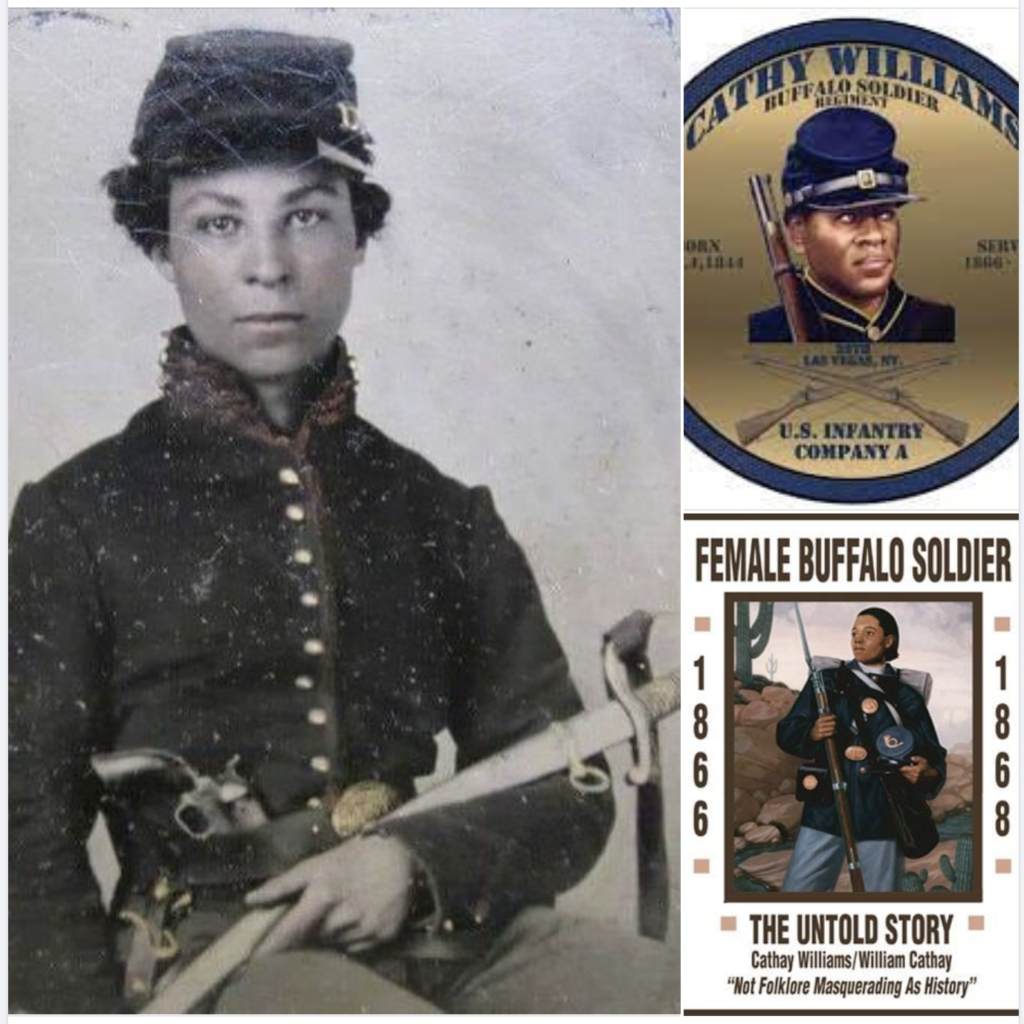

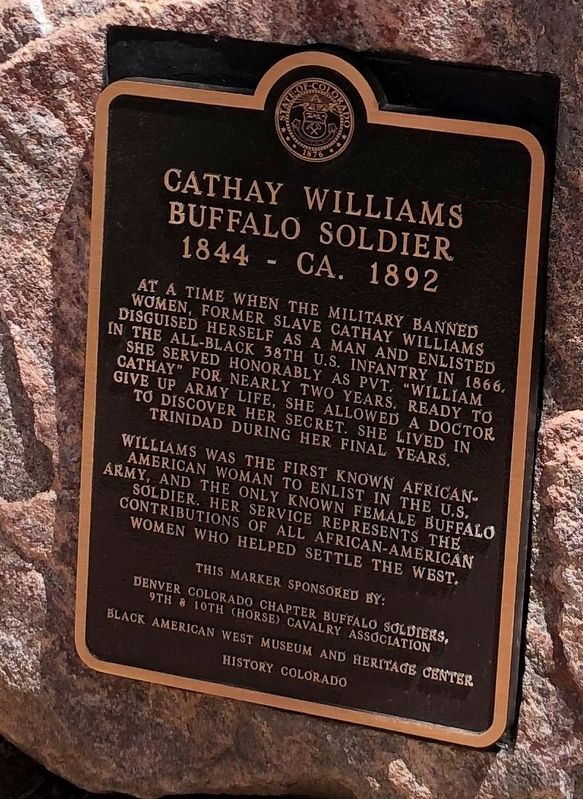

“William Cathay enlisted in the U.S. Army on Nov. 15, 1866, for a three-year term. Since the Army didn’t do full physical examinations during this period, it would allow Cathay to serve out most of the contract, even though William Cathay was Cathay Williams, a woman posing as a man. But her service started long before she was old enough to enlist.

She would end her Army career as the Army’s only female Buffalo Soldier and the first Black woman to enlist.

Advertisement

She was born in 1844 in Missouri to a free father and an enslaved woman, which made her legally a slave. When the Union Army captured Jefferson City, slaves were considered “contraband” so Cathay Williams and slaves like her supported the Union Army as camp followers. She and others cooked for the troops cleaned their laundry, or acted as nurses.

According to stories told by Williams after her enlistment and discharge, she followed the Union Army throughout the West and was present for many of its most important engagements, including the Siege of Vicksburg and Gen. William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea.

She had begun supporting the Union Army at age 17. By the time the war ended, she was 22 years old, but the Army was all she’d known as an adult. With the Civil War over and slaves across the country freed, she enlisted in the Army, posing as William Cathay, and was sent to the 38th U.S. Infantry Regiment. The unit was organized in 1866 as one of six segregated Black infantry regiments, which became collectively known as “Buffalo Soldiers.” They were the first all-black infantry regiments of the regular Army formed during peacetime.

The 38th’s primary mission was protecting the construction of the intercontinental railroads, the first of which was completed in 1869, when the 38th merged with the 41st Infantry Regiment. The 41st was also a segregated unit, which had spent the time in Louisiana and Texas. The only thing that kept Williams from completing her enlistment was a disease that would be eliminated in the United States 20 years later: smallpox. She contracted the virus not long after signing up for the Army. After recovering, she rejoined the 38th, which was then in New Mexico for the railroads’ east-west continental connection.

After she suffered years of stress on her body, frequent hospitalizations, and never fully recovered from her smallpox infection, Army doctors finally took a closer look at William Cathay and discovered the truth. She was honorably discharged in 1868 and moved to Fort Union, New Mexico, where she went to work as a cook.

The Buffalo Soldiers went on to fight in the Indian Wars of the American West and the Spanish-American War. Cathay Williams moved to Colorado. She became a seamstress and her story remained untold in the wider press for almost a decade. In 1874, a reporter from the St. Louis Daily Times heard rumors of a Black woman who had served in and was honorably discharged from the Army and published an account two years later. Williams’ medical troubles followed her for the rest of her life. She was known to have suffered from neuralgia (pain along certain nerves) and diabetes (from which she lost all her toes), but her applications for medical pensions from the Army were denied. No one knows precisely when or where she died or at what age.

The Global Association of Buffalo Soldiers Recognition and Riding Club Inc. finally recognized Williams’ historic service after almost 150 years. In 2015, it unveiled a monument bench for Pvt. Cathay Williams on the Walk of Honor at the National Infantry Museum in Columbus, Georgia.”

– Blake Stilwell

~*****~

Black Servicewomen

Cathay Williams

Cathay Williams was born a slave in Independence, Mo., in 1844. As she grew up, she worked as a house slave on a plantation near Jefferson City, Mo. Early in the Civil War, Jefferson City was conquered by Union troops, and captured slaves were pressed into service for the Union Army. Williams was forced to serve in the 8th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment. She traveled with the Union Army through Arkansas, Louisiana, and Georgia. When the Civil War ended, Williams was working at Jefferson Barracks, south of St. Louis.

After the Civil War, the U.S. Congress established the first peacetime all-black regiments in the U.S. Army. They were known as Buffalo Soldiers. Cathay Williams posed as a man, called herself William Cathay, and joined the 38th Regiment. She is now known to be the first African-American female to enlist, and the only person believed to have served in the U.S. Army posing as a man. After being organized at Jefferson Barracks, the 38th Infantry was stationed in the New Mexico Territory and along the transcontinental railroads during their construction. Williams contracted smallpox shortly after enlisting and was hospitalized frequently after that. The post-surgeon finally discovered William Cathay was a woman, and she was discharged from the army in 1868.

“There is no gravestone marking the final resting place of Cathay Williams. Nor is there one for her alter ego, Private William Cathey, who served with the 38th Infantry on the western frontier from 1866 to 1868. “

Cathy Williams

1862 US Union soldier Cathy Williams. She had to pose as a male to be enlisted. She was part of the 38 Regiment, Infantry Division, and was called a Buffalo Soldier.

Cathay Williams was an African-American soldier who enlisted in the United States Army under the pseudonym William Cathay. She was the first Black woman to enlist, and the only documented woman to serve in the United States Army posing as a man during the American Indian Wars. (Wikipedia)

Born: September 1844, Independence, MO

Died: 1893, Trinidad, CO

Other names: John Williams, William Cathay

Rank: Private

Unit: 38th U.S. Infantry Regiment, U.S. Army (Buffalo soldier)

Years of service: 1866–1868

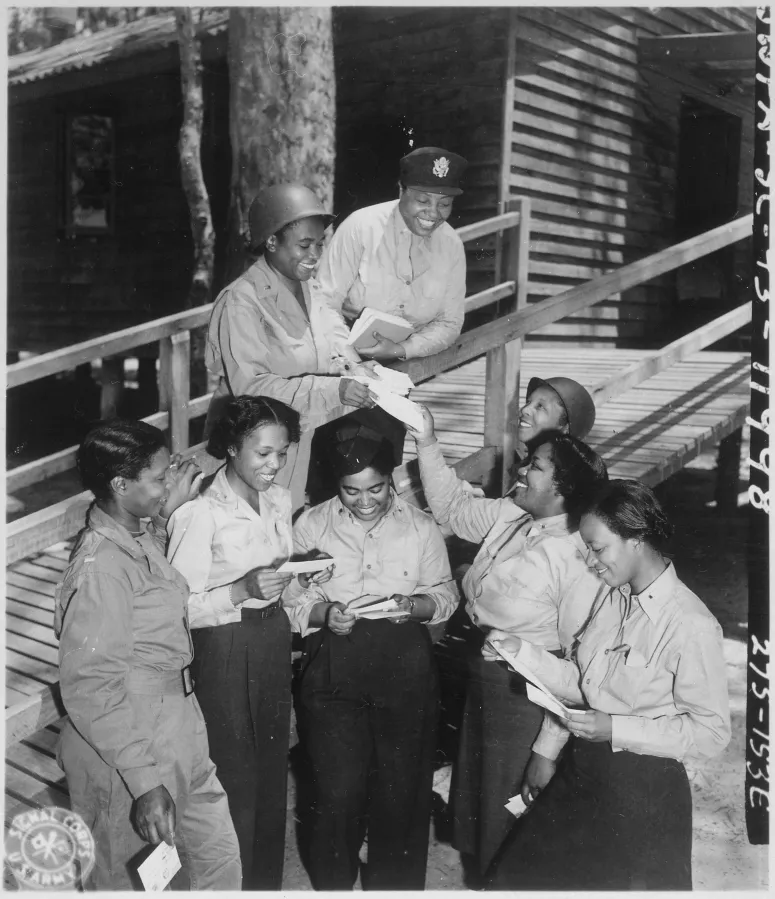

African American WACS

Group of African American members of the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) posing for a group photo in uniform during World War 2, 1940. (Photo by Afro-American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images).

The Senate passed legislation to award the only all-Black Women’s Army Corps (WACs) deployed overseas during World War II the Congressional Gold Medal. The “Six Triple Eight” self-contained postal unit completed the seemingly impossible task of tackling the mail backlog during the final months of the war.

Who were the WACs and what did they do?

Women’s Army Corps (WAC), a U.S. Army unit created during World War II to enable women to serve in noncombat positions. Never before had women, except nurses, served within the ranks of the U.S. Army. With the establishment of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), more than 150,000 did so.

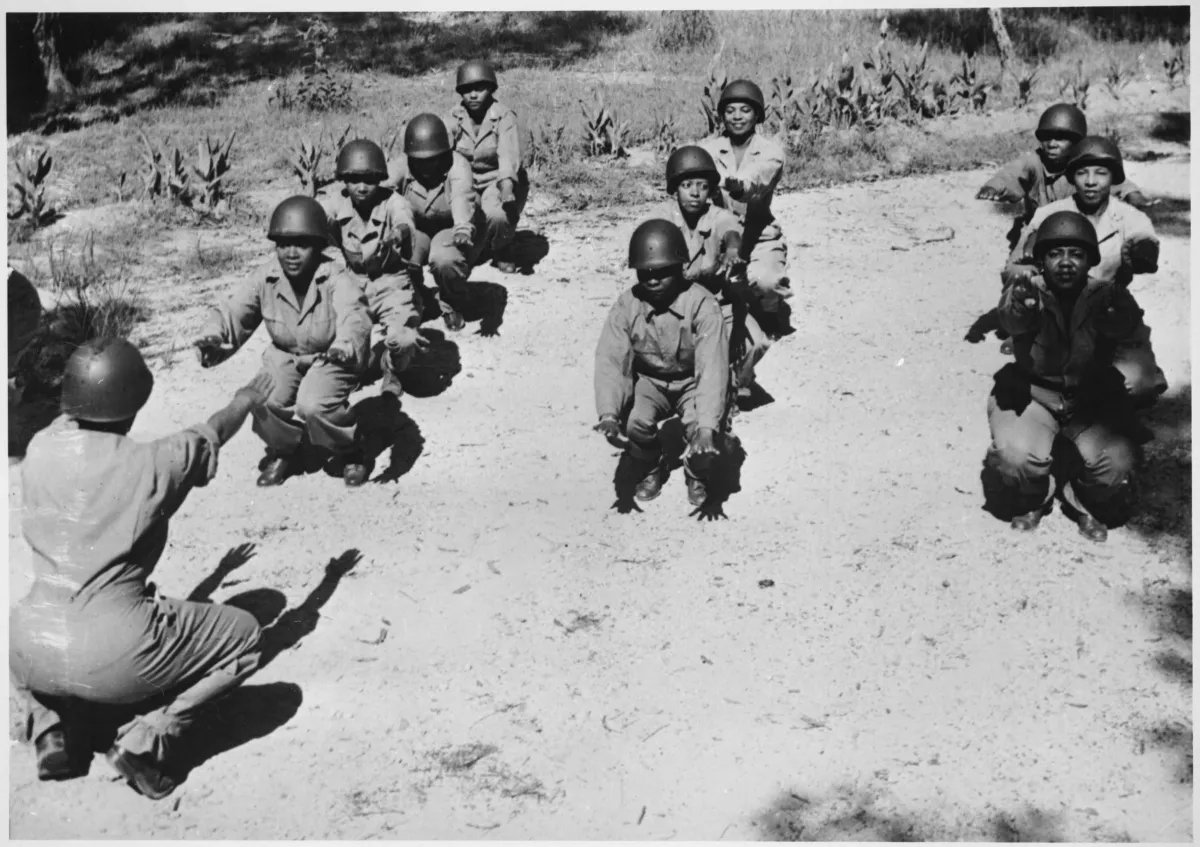

African-American women joined the WAC during World War II seeking opportunity and a chance to support the war effort. For some, the experience was disappointing. Courtesy of the National Archives at College Park/Wikimedia Commons. – Captain Adams drilling her company at the first W.A.A.C. training center in Fort Des Moines, Iowa, in 1943. – Credit… National Archives.

“In January 1945, a C-54 cargo plane carrying a group of young Army officers departed an Air Transport Command terminal in Washington for war-torn Europe. Among the passengers was a 26-year-old major named Charity Adams, who was quietly making history as the first African-American commanding officer in the Women’s Army Corps to be deployed to a theater of war. As the plane ascended over the Atlantic, she still wasn’t sure where she was headed or what she would be doing there. Her orders, marked “Secret,” were to be unsealed in flight. When she opened the envelope, the documents revealed only that her destination was somewhere in the British Isles; she would be briefed on the particulars of the mission once on the ground.

A couple of weeks later, Adams stood on a windswept parade field in Birmingham, England, addressing a formation of hundreds of Black soldiers in khaki-skirted uniforms. She had been placed in command of a battalion that would soon number 855 women. She could see that many were scared and tired, still reeling from a treacherous 11-day journey from the United States by sea spent dodging torpedoes and German U-boats. Groans rippled through the ranks as Adams explained that they would begin work immediately. As the newly created 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, their mission was neither glamorous nor particularly thrilling. The work would be grueling, the hours long, and what little sleep they were allotted would be prone to interruption by air raids. Progress would be measured by the depletion of undelivered mail they had been summoned to England to sort out. With the war now at its bloody peak, mail was indispensable for morale, but delivering it had become a towering logistical challenge. The backlog piled haphazardly in cavernous hangars, amounted to more than 17 million letters and packages addressed to Allied military personnel scattered across Europe.”

Despite her can-do attitude, Adams believed that she and her troops had been set up for failure. Before the formation of the Six Triple Eight, as the battalion was known, it was unfathomable that a unit composed entirely of Black women would be posted overseas and trusted with such a monumental task. The Six Triple Eight was an experiment — a pass-fail test to determine the value Black women brought to the military. Years of unyielding pressure from civil rights activists, including the First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, had convinced the War Department to give them a shot, but those who strongly opposed their inclusion in the ranks expected to be validated by seeing them fail. “The eyes of the public would be upon us, waiting for one slip in our conduct or performance,” Adams later recalled in her memoir. She knew that simply getting the job done wouldn’t be enough. The Six Triple Eight would need to not only pass the test but also, as Adams wrote, prove to “be the best WAC unit ever sent into a foreign theater.”

A pastor’s daughter from Columbia, S.C., Adams dropped out of graduate school to join the war effort in the summer of 1942, after the newly formed Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (W.A.A.C.) announced that it was accepting 40 Black women into its first officer-candidate school. Black civic leaders were calling for African-American men and women to volunteer for military service and fight for equal rights overseas; as Adams soon learned, however, the arbitrary constraints of Jim Crow applied even in matters of national security. At the ceremony that culminated the W.A.A.C. officer course, the candidates were commissioned as third officers, equivalent to Army second lieutenants, in alphabetical order by last name. Though Adams topped the list, she watched all the white candidates cross the stage before her name was called and she officially became the first Black woman ever commissioned in the corps.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/17/magazine/6888th-battalion-charity-adams.html

They were administrators, welders, railroad conductors, and more.

They were administrators, welders, railroad conductors, and more.