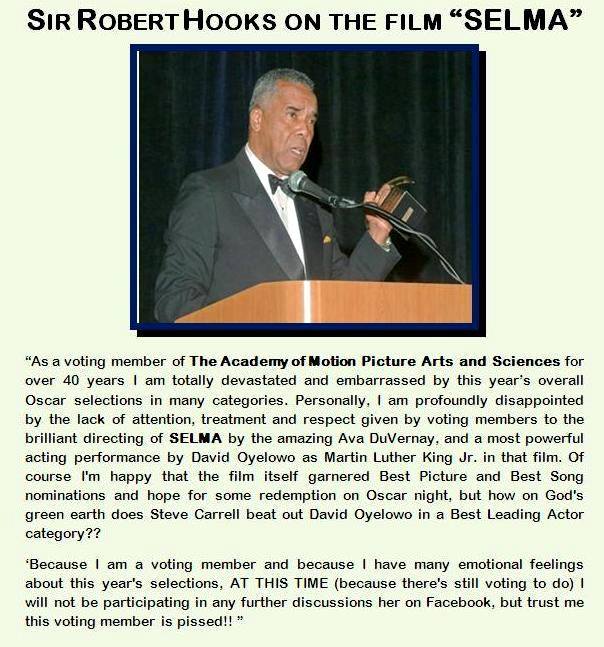

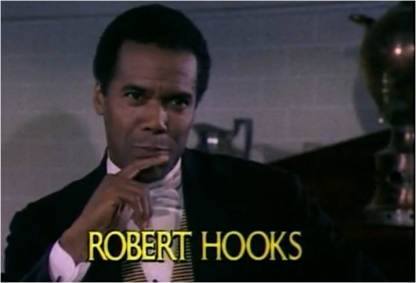

Filmography

2016 The Actor’s Choice (TV Series)

– Robert Hooks (2016)

2011 Reed Between the Lines (TV Series)

Monroe Reed

– Let’s Talk About Dating Advice (2011) … Monroe Reed

2007 Lincoln Heights (TV Series)

Det. Chase

– Obsession (2007) … Det. Chase (uncredited)

2003 Dragnet (TV Series)

Captain

– The Big Ruckus (2003) … Captain

2000 Seventeen Again (TV Movie)

Grandpa Gene

1999-2000 The Hoop Life (TV Series)

Willis Barry

– The Second Chance (2000) … Willis Barry

– The Talented Tenth (2000) … Willis Barry

– The Back Stretch (2000) … Willis Barry

– A Little Yen (2000) … Willis Barry

– Rock, Salt, and Nails (2000) … Willis Barry

1999 Clueless (TV Series)

Benjamin Davenport

– A Test of Character (1999) … Benjamin Davenport

1998 Free of Eden (TV Movie)

Joe Sherman

1998 Glory & Honor (TV Movie)

Thomas

1997 The Parent ‘Hood (TV Series)

Lawrence

– Mother and Law (1997) … Lawrence

1996 Diagnosis Murder (TV Series)

City Attorney Andrew Chivers

– Murder by Friendly Fire (1996) … City Attorney Andrew Chivers

1996 Fled

Lt. Clark

1995 The Commish (TV Series)

Capt. M. A. Daniels

– Off-Broadway: Part 2 (1995) … Capt. M. A. Daniels

– Off-Broadway: Part 1 (1995) … Capt. M. A. Daniels

1994-1995 Seinfeld (TV Series)

Joe / Joe Temple

– The Diplomat’s Club (1995) … Joe

– The Couch (1994) … Joe Temple

1995 Abandoned and Deceived (TV Movie)

Doctor Peck

1994-1995 M.A.N.T.I.S. (TV Series)

Mayor Lew Mitchell

– Spider in the Tower (1995) … Mayor Lew Mitchell

– Revelation (1994) … Mayor Lew Mitchell

– Thou Shalt Not Kill (1994) … Mayor Lew Mitchell

1986-1995 Murder, She Wrote (TV Series)

Kendall Ames / Everett Charles Jensen

– The Scent of Murder (1995) … Kendall Ames

– Christopher Bundy – Died on Sunday (1986) … Everett Charles Jensen

1994 Family Matters (TV Series)

Dr. Smiley

– Good Cop, Bad Cop (1994) … Dr. Smiley

1993 The Sinbad Show (TV Series)

Mr. Winters

– My Daughter’s Keeper (1993) … Mr. Winters

1993 The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air (TV Series)

Dean Morgan

– It’s Better to Have Loved and Lost It… (1993) … Dean Morgan

THE FRESH PRINCE OF BEL-AIR — “It’s Better to Have Loved and Lost it…” Episode 5 — Pictured: (l-r) Robert Hooks as Dean Morgan, Alfonso Ribeiro as Carlton Banks — (Photo by Alice S. Hall/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images)

THE FRESH PRINCE OF BEL-AIR — “It’s Better to Have Loved and Lost it…” Episode 5 — Air Date 10/11/1993 — Pictured: (l-r) Alfonso Ribeiro as Carlton Banks; Natalie Venetia Belcon as Joann Morgan; Robert Hooks as Dean Morgan (Photo by Alice S. Hall/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images)

THE FRESH PRINCE OF BEL-AIR — “It’s Better to Have Loved and Lost it…” Episode 5 — Air Date 10/11/1993 — Pictured: (l-r) Alfonso Ribeiro as Carlton Banks; Natalie Venetia Belcon as Joann Morgan; Will Smith as William ‘Will’ Smith; Robert Hooks as Dean Morgan (Photo by Alice S. Hall/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images)

1993 Posse

King David

1993 Reasonable Doubts (TV Series)

Kane

– Trust Me on This: Part 2 (1993) … Kane

– Trust Me on This: Part 1 (1993) … Kane

1993 L.A. Law (TV Series)

Judge Earl Gregory

– Parent Trap (1993) … Judge Earl Gregory

– Bare Witness (1993) … Judge Earl Gregory

1993 Out All Night (TV Series)

Cliff Emory

– A Date with a Diva (1993) … Cliff Emory

1992 Passenger 57

Dwight Henderson

1991 The Royal Family (TV Series)

Langston White

– A Mid-Summer’s Night Barbeque (1991) … Langston White

1990 The Flash (TV Series)

Chief Arthur Cooper

– Pilot (1990) … Chief Arthur Cooper

1990 Heat Wave (TV Movie)

Reverend Brooks

1990 Appearances (TV Movie)

Wesley

A Different World (TV Series)

Phillip Dalton

– Risky Business (1989) … Phillip Dalton

1983-1988 Hotel (TV Series)

Joe Durran / Frank ‘Squire’ Vance

– Aftershocks (1988) … Joe Durran

– Choices (1983) … Frank ‘Squire’ Vance

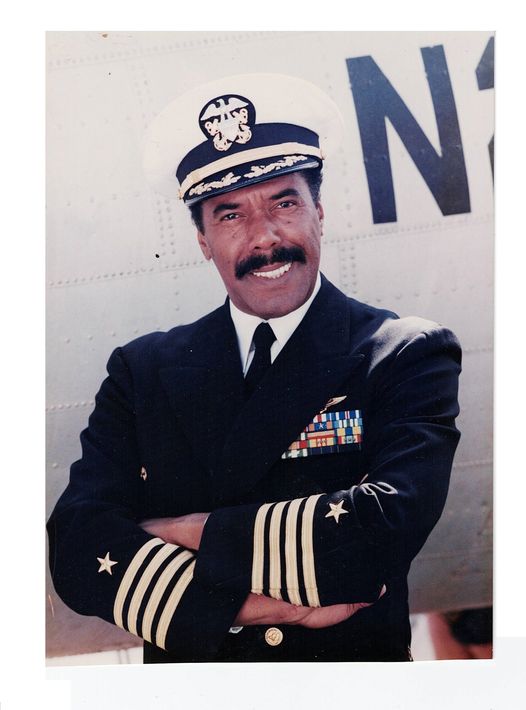

1988 Supercarrier (TV Series)

Commander Jim Coleman

– Deadly Enemies (Pilot) (1988) … Commander Jim Coleman

“One of the most honored assignments for me as an actor was portraying Admiral Jim Coleman (Commander of the Air Group {CAG}, on the fictional aircraft carrier, the USS Georgetown. The ABC Miniseries “Supercarrier”(circa 1987-88) was filmed aboard the USS John F. Kennedy, and for three weeks on a qualification cruise in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, I experienced an amazing time in a U.S. Navy uniform. Never having served in the military, for me, it was one of the most gratifying acting assignments of my career. Directed by (former child film star) Jackie Cooper, the cast was superb, including Ken Olandt, Alex Hyde-White, Richard Jaeckel, Craig Stevens, Denise Nicholas, and a great supporting cast. The Miniseries ran into Network/producer script and story problems and only six of the eight episodes were aired. But the honor was all mine, and having many friends and relatives who served with great distinction for our country, FOR REAL in their lives, the series “Supercarrier” was an acting highlight for me.”

1987 J.J. Starbuck (TV Series)

Lt. Lavelle Caspersons

– The 6 % Solution (1987) … Lt. Lavelle Caspersons

1987 21 Jump Street (TV Series)

Dr. Tony Hoffs

– In the Custody of a Clown (1987) … Dr. Tony Hoffs

1987 Head of the Class (TV Series)

Mr. Nevins

– Crimes of the Heart (1987) … Mr. Nevins

1986 227 (TV Series)

Congressman Rivers

Robert Hooks and Jackee Harry { 227}

– Washington Affair (1986) … Congressman Rivers

1986 D.C. Cops (TV Movie)

Nathan Jackson

1986 Blacke’s Magic (TV Series)

– Last Flight from Moscow (1986)

1985 Words by Heart (TV Movie)

Ben Sills

1983-1985 T.J. Hooker (TV Series)

Police Detective Joe Fisher / Lt. Ellis

– Trackdown (1985) … Police Detective Joe Fisher

– The Trial (1983) … Lt. Ellis

1985 The Execution (TV Movie)

Alton Reese

1985 V (TV Series)

George Caniff

– The Hero (1985) … George Caniff

1984 Star Trek III: The Search for Spock

Admiral Morrow

1984 Dynasty (TV Series)

Dr. Walcott

– The Birthday (1984) … Dr. Walcott

– Steps (1984) … Dr. Walcott

– The Vigil (1984) … Dr. Walcott

1983 Feel the Heat (TV Series)

Captain Barney Hill

1983 Hardcastle and McCormick (TV Series)

Lieutenant Carlton

– Man in a Glass House (1983) … Lieutenant Carlton

1983 Hart to Hart (TV Series)

Inspector Jordan

– Bahama Bound Harts (1983) … Inspector Jordan

1982 The Devlin Connection (TV Series)

Gaylord

– Allison (1982) … Gaylord

1982 Sister, Sister (TV Movie)

Harry Burton

1982 Fast-Walking

William Galliot

1982 WKRP in Cincinnati (TV Series)

Prosecutor

– Circumstantial Evidence (1982) … Prosecutor

1982 Cassie & Co. (TV Series)

Matthews

– The Golden Silence (1982) … Matthews

1982 Quincy M.E. (TV Series)

Sergeant LeBatt

– Bitter Pill (1982) … Sergeant LeBatt

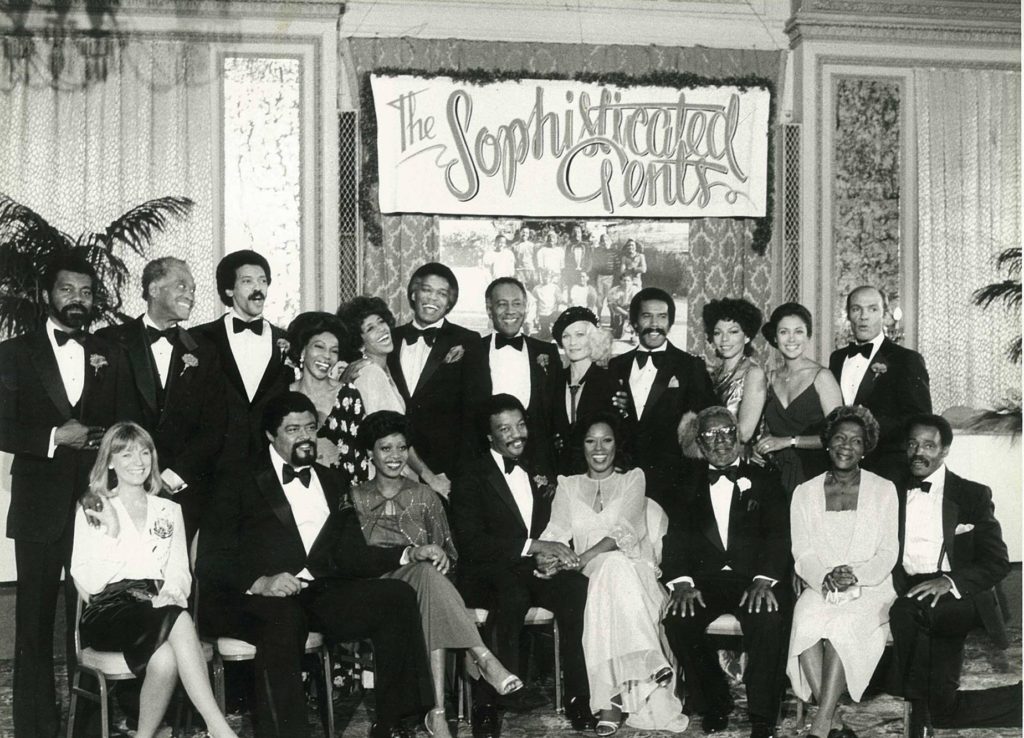

1981 The Sophisticated Gents (TV Series)

Ezra ‘Chops’ Jackson

– Episode #1.3 (1981) … Ezra ‘Chops’ Jackson

– Episode #1.2 (1981) … Ezra ‘Chops’ Jackson

– Episode #1.1 (1981) … Ezra ‘Chops’ Jackson

The Sophisticated Gents was a TV miniseries that aired on three consecutive nights from September 29 to October 1, 1981, on NBC. The miniseries was based on the novel “The Junior Bachelor Society” by John A. Williams. Although the production of the project ended in 1979, NBC did not air the miniseries until almost two years later.

Melvin Van Peebles, Robert Hooks, Ron O’Neal, Dick Anthony Williams, Thalmus Rasulala, Rosey Grier, Bernie Casey, Raymond St. Jacques, and Paul Winfield.

TV Movie “The Sophisticated Gents” (circa 1981). (How many do you recognize?) This is a photo assemblage of the “Gents” and their Wives at the ‘reunion’s formal black-tie evening! “Gents” was one of the most memorable films I ever worked on, with so many of my personal and brilliantly talented friends, several of whom have passed on to that other plain. What an ensemble of great actors, and what fun we all had together.

Thalmus Rasualla,

Robert Earl Jones,

Dick Anthony Williams,

Marlene Warfield,

Janet MacLachlan,

Bernie Casey,

Raymond St. Jacques,

Vera Miles,

Robert Hooks,

Rosalind Cash,

Denise Nicholas,

Leigh Hamilton,

Joanna Miles,

Ron O’Neal.

*

– FIRST ROW –

Bibi Besch,

Rosey Grier,

Alfre Woodard,

Paul Winfield,

Ja’net Dubois,

Sonny Jim Gaines,

Beau Richard,

Melvin Van Peoples,

Beah Richards,

Melvin Van Peebles.

Set in the mid-1970s, The Sophisticated Gents centers upon the brotherhood relationship shared by nine African-American men who bonded during their childhood when they were members of “The Sophisticated Gents” sports club.

The club was founded by their coach, Charles “Chappie” Davis (Sonny Jim Gaines), to actively involve the boys in their inner city, Los Angeles community. Promoting excellence in sports but also in character, the boys grew to be hardworking and accomplished, whether in blue-collar labor, community leadership, business, or crime.

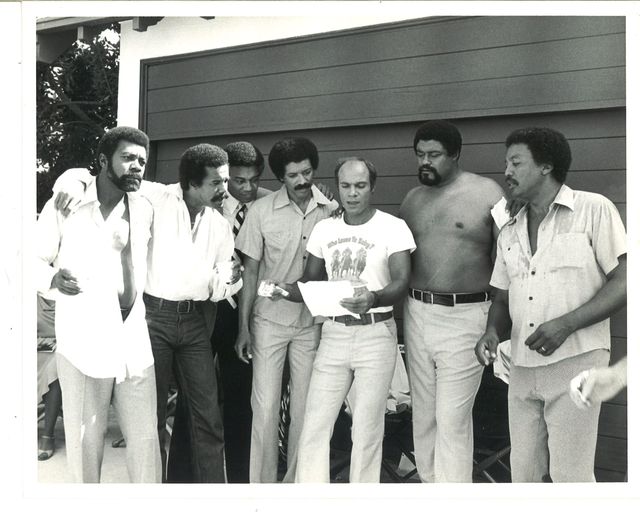

Amazing and brilliant actors (I just happen to be there) taking a break from one of the informal confabs on the script of Sophisticated Gents. (From l to r) …Thalmus Rasullala, Me, Bernie Casey, Dick Anthony Williams, Ron O’Neal, Rosie Grier, and Paul Winfield! …What a great experience in my career!

1981 Madame X (TV Movie)

Dist. Atty. Roerich

1981 The Oklahoma City Dolls (TV Movie)

John Miller

1980 The White Shadow (TV Series)

Dr. Luther Tucker

– Reunion: Part 2 (1980) … Dr. Luther Tucker

– Reunion: Part 1 (1980) … Dr. Luther Tucker

1980 The Facts of Life(TV Series)

Mr. Ramsey

– Overachieving (1980) … Mr. Ramsey

THE FACTS OF LIFE — “Overachieving” Episode 5 — Aired 3/12/80 — Pictured: (l-r) Robert Hooks as Mr. Ramsey, Kim Fields as Dorothy ‘Tootie’ Ramsey, Charlotte Rae as Mrs. Edna Ann Garrett– Photo by NBCU Photo Bank

THE FACTS OF LIFE — “Overachieving” Episode 5 — Aired 3/12/80 — Pictured: (l-r) Charlotte Rae as Mrs. Edna Ann Garrett, Kim Fields as Dorothy ‘Tootie’ Ramsey, Robert Hooks as Mr. Ramsey — Photo by NBCU Photo Bank

THE FACTS OF LIFE — “Overachieving” Episode 5 — Aired 3/12/80 — Pictured: (l-r) Charlotte Rae as Mrs. Edna Ann Garrett, Kim Fields as Dorothy ‘Tootie’ Ramsey, Robert Hooks as Mr. Ramsey — Photo by NBCU Photo Bank

Voices Of Our People (1981)

Here’s a classic throwback image of the original founders of ‘The Media Forum’, from the Emmy Award winning PBS/KCET television presentation “Voices Of Our People, In Celebration Of Black Poetry” (circa 1981.) Ladies in front: (left to right) Janet MacLaughlan, Denise Nicholas and Tracey Lyles- Men in back: Charles Floyd Johnson, Me, and Brock Peters. The Media Forum organization advocated for more and better opportunities for Black artists and other professionals of color, in front of and behind Hollywood’s film and TV cameras!

1980 Trapper John, M.D. (TV Series)

Sykes

– Boom! (1980) … Sykes

1979 Hollow Image (TV Movie)

Paul Hendrix

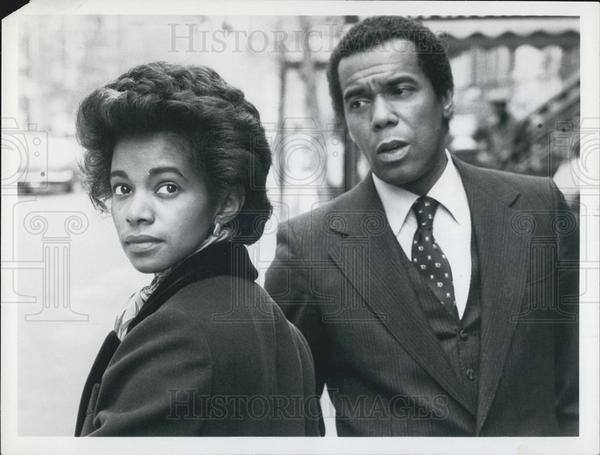

New York, NY – 1979: Robert Hooks appearing in the ABC tv movie ‘Hollow Image‘. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

New York, NY – 1979: (L-R) Robert Hooks, Samuel E Wright, S Pearl Sharp appearing in the ABC tv movie ‘Hollow Image‘. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

Saundra (S.Pearl) Sharp and me- starring in the television film “Hollow Image” by Lee Hunkins. The film also featured Dick Anthony Williams, Morgan Freeman, and Hattie Winston Wheeler.

1979 Time Express (TV Series)

John Slocum

– Rodeo/Cop (1979) … John Slocum

1979 Backstairs at the White House(TV Mini-Series)

Doorman and Presidential Barber John Mays / Chief Barber John Mays

– Episode #1.4 (1979) … Doorman and Presidential Barber John Mays

– Episode #1.3 (1979) … Doorman and Presidential Barber John Mays

– Episode #1.2 (1979) … Doorman and Presidential Barber John Mays

– Episode #1.1 (1979) … Chief Barber John Mays

1978 The Eddie Capra Mysteries (TV Series)

– Dying Declaration (1978)

1978 A Woman Called Moses (TV Series)

William Still

– Episode #1.2 (1978) … William Still

– Episode #1.1 (1978) … William Still

1978 The Courage and the Passion (TV Movie)

Maj. Stanley Norton

1978 To Kill a Cop (TV Movie)

Captain Pete Rolfe

1977 Airport ’77

Eddie

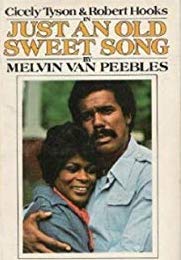

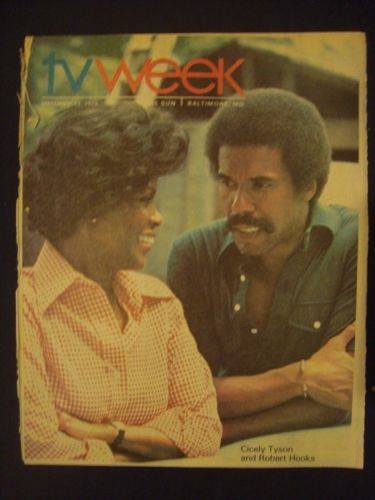

1976 Just an Old Sweet Song (TV Movie)

Nate Simmons

1976 The Killer Who Wouldn’t Die (TV Movie)

Commissioner Frank Wharton

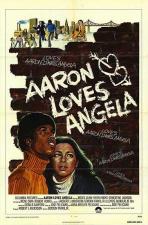

1975 Aaron Loves Angela

Beau.

1975 Petrocelli (TV Series)

Dave Hill

– Too Many Alibis (1975) … Dave Hill

1975 Police Story (TV Series)

Police Detective Ernie Tillis

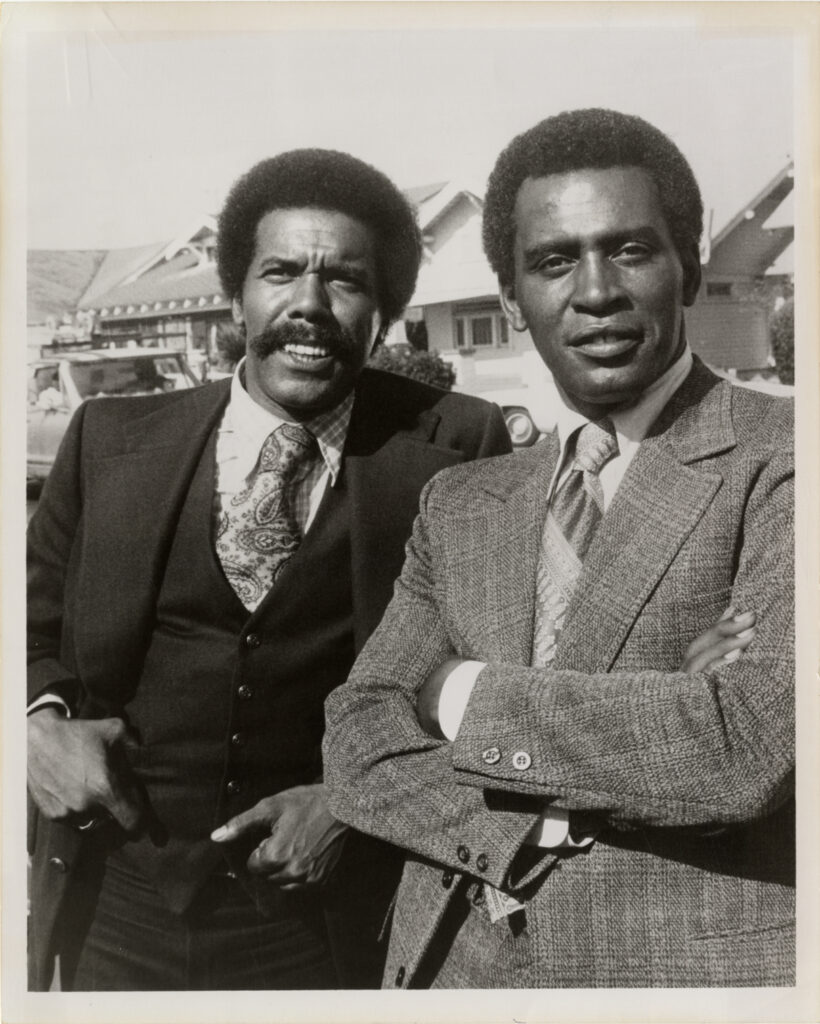

Robert Hooks and Scoey Mitchell in an episode of “Police Story.” ‘The Cut Man Caper’

– The Cut Man Caper (1975) … Police Detective Ernie Tillis

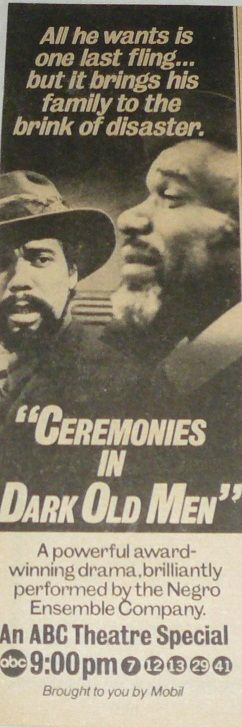

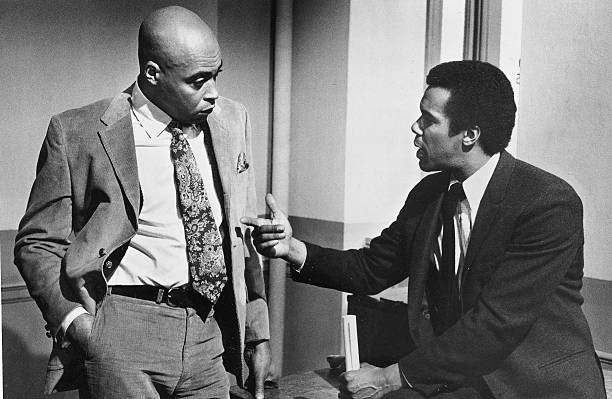

1975 Ceremonies in Dark Old Men (TV Movie)

Blue Haven

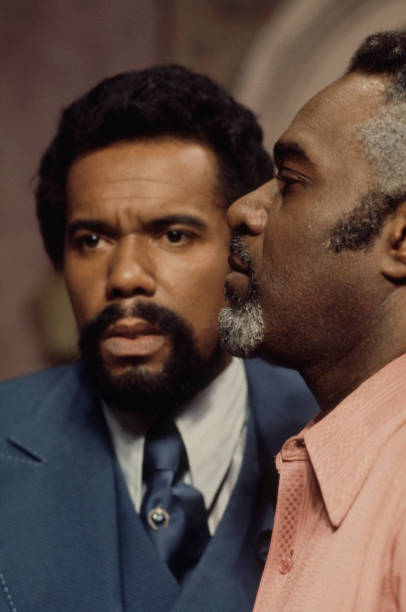

Robert Hooks, Douglas Turner Ward – Ceremonies in Dark Old Men’. (Photo by Bert Andrews /American Broadcasting Companies via Getty Images)

‘Ceremonies in Dark Old Men’. (Photo by Bert Andrews /American Broadcasting Companies via Getty Images)

1975: Robert Hooks appearing on the ABC tv movie ‘Ceremonies in Dark Old Men‘. (Photo by Bert Andrews /American Broadcasting Companies via Getty Images)

Robert Hooks and Douglas Turner Ward, ‘Ceremonies in Dark Old Men‘. (Photo by Bert Andrews /American Broadcasting Companies via Getty Images)

Unspecified – 1975: (L-R) Godfrey Cambridge, Douglas Turner Ward, J Eric Bell, Glynn Turman, Robert Hooks appearing on the ABC tv movie ‘Ceremonies in Dark Old Men’. (Photo by Bert Andrews /American Broadcasting Companies via Getty Images)

Robert Hooks, Godfrey Cambridge, J Eric Bell, Douglas Turner Ward

Douglas Turner Ward, Godfrey Cambridge, Robert Hooks, Glynn Turman – (Photo by Bert Andrews /American Broadcasting Companies via Getty Images)

1969-1974 The F.B.I. (TV Series)

Wilcox / Steven Harber

– Deadly Ambition (1974) … Wilcox

– Silent Partner (1969) … Steven Harber

(L-R) Robert Hooks, William Reynolds appearing on Walt Disney Television via Getty Images’s ‘The FBI’. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

Robert Hooks appearing on Walt Disney Television via Getty Images The FBI‘. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

1974 The Streets of San Francisco (TV Series)

Joe Joplin

– Rampage (1974) … Joe Joplin

1973 Stone (TV Movie)

1973 Marcus Welby, M.D. (TV Series)

Joe Lucas

MARCUS WELBY, M.D. – “Nguyen” – Aired on November 27, 1973. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images) ROBERT YOUNG; ERIC WOODS; ROBERT HOOKS; MICHAEL MASTRO

MARCUS WELBY, M.D. – “Nguyen” – Aired on November 27, 1973. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images) ROBERT YOUNG; ROBERT HOOKS; ERIC WOODS; MICHAEL MASTRO

– Nguyen (1973) … Joe Lucas

1973 Trapped (TV Movie)

Sergeant Connaught

1973 McMillan & Wife (TV Series)

Sam

Robert Hooks and Susan Saint James – McMillan and Wife – ” The Devil you Say“

– The Devil You Say (1973) … Sam

1973 The Rookies (TV Series)

Barney Miller

– Deadly Cage (1973) … Barney Miller

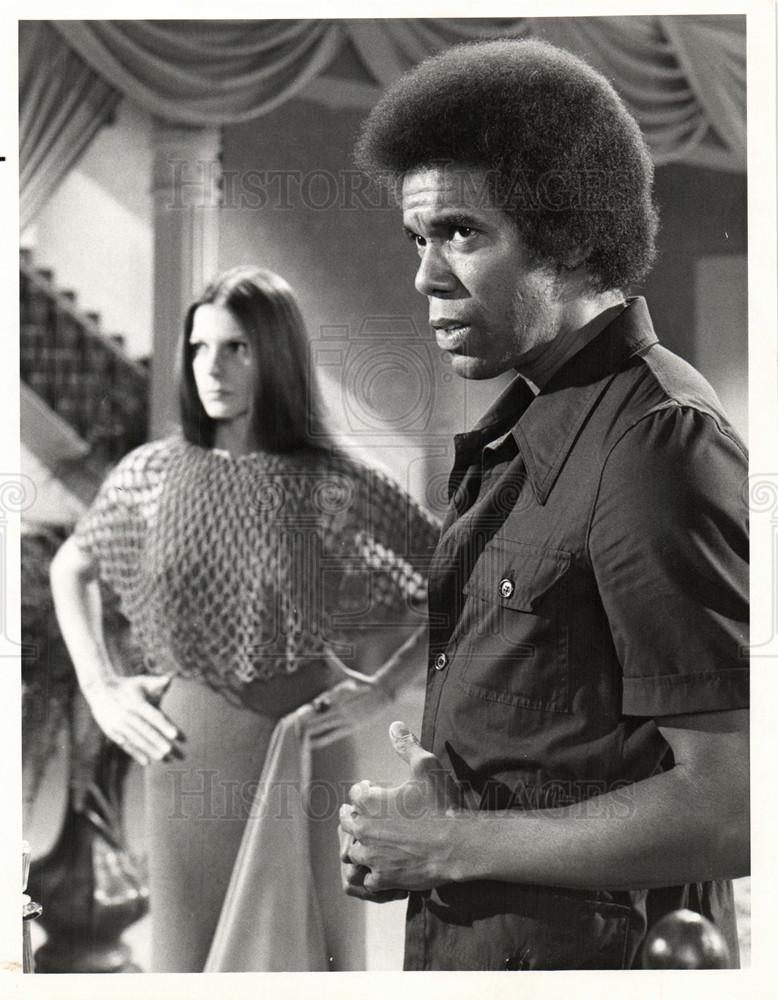

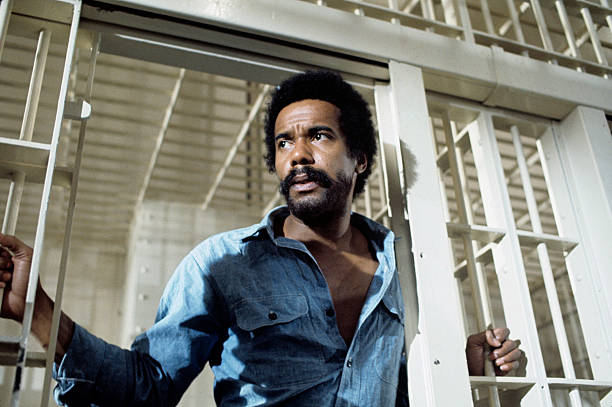

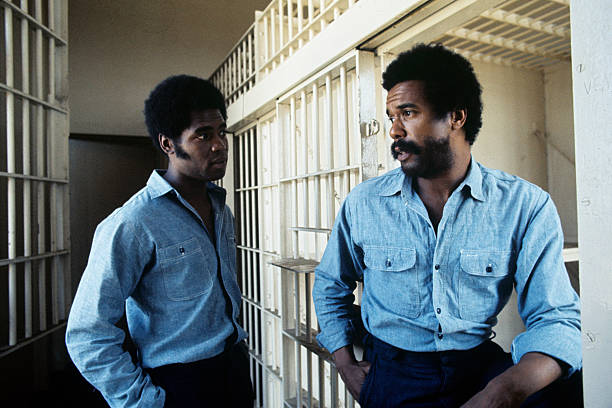

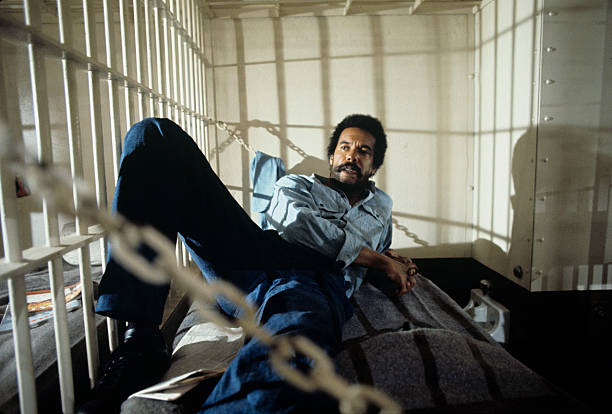

THE ROOKIES – “Deadly Cage” 9/24/73 Robert Hooks (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

UNITED STATES – APRIL 10: THE ROOKIES – “Deadly Cage” 9/24/73 Georg Stanford Brown, Robert Hooks (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

UNITED STATES – APRIL 10: THE ROOKIES – “Deadly Cage” 9/24/73 Robert Hooks (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

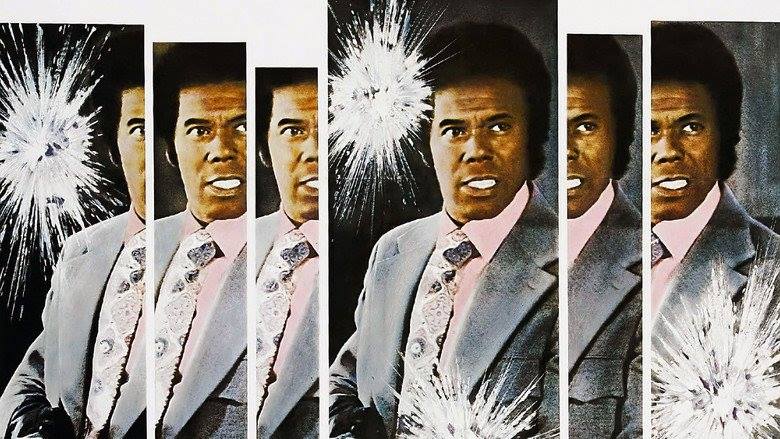

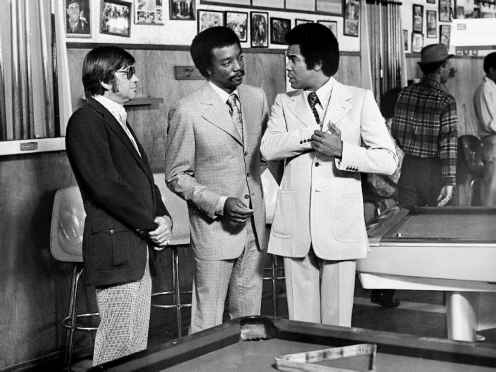

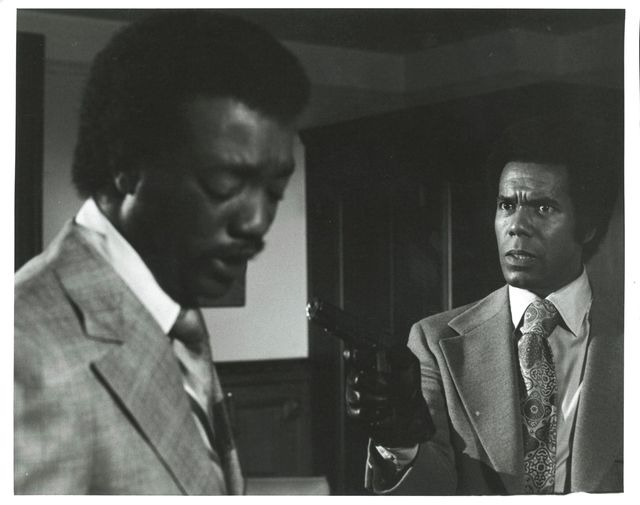

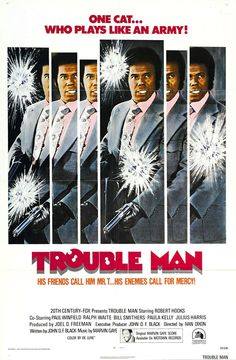

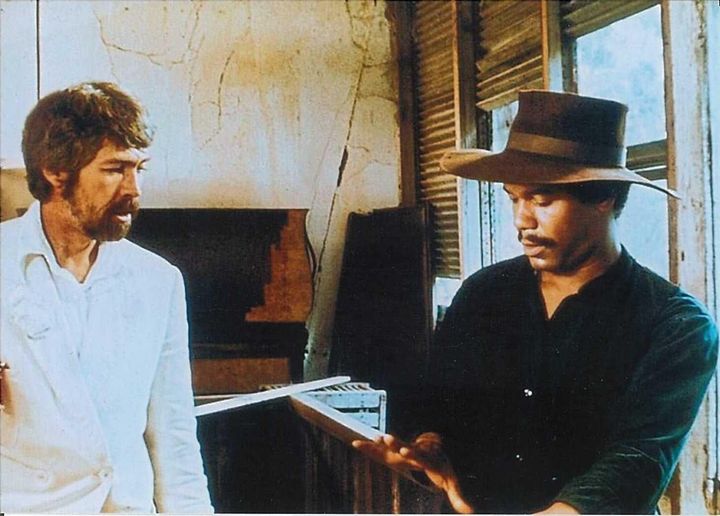

1972 Trouble Man Mr. T

“In Trouble Man, Robert Hooks, far right, is ”Mr. T,” a well-tailored hero who opposes the crooked duo of Chalky (Paul Winfield, center) and Pete (Ralph Waite).”

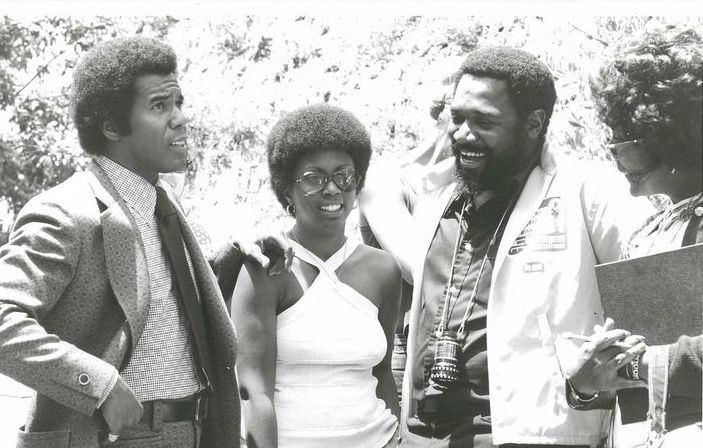

We’re on location in LA shooting “Trouble Man” here is my lovely daughter Cecelia visiting from DC. Our brilliant director Ivan Dixon wanted to show CeCe everything we had scheduled for the day, and she was blown away at the process! Our script supervisor Margaret Varian, made sure CeCe knew everything to do with the day’s shoot ( a lot of gun shooting if I recall). It was a great event for CeCe seeing her Dad acting his “Mr.T” thang!! and experiencing how Hollywood treated visitors of the lead actor!

The late great actor Paul Winfield gets on the wrong side of justice and in the way of a serious crime-solving Mr “T” in a scene from the hit action thriller “Trouble Man”! Paul was one of America’s finest stage and screen artists and left us much too early in his career, but his acting contributions to America’s entertainment industry were tremendous!

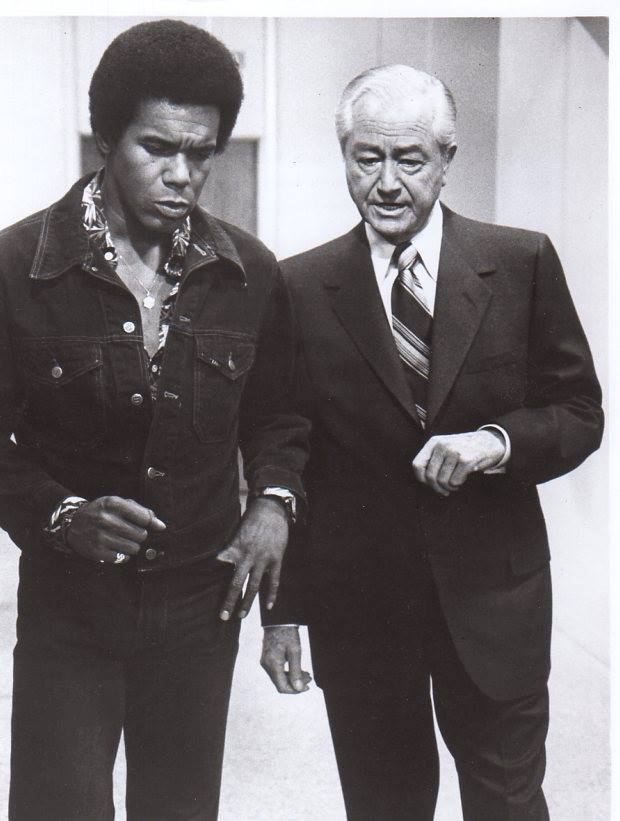

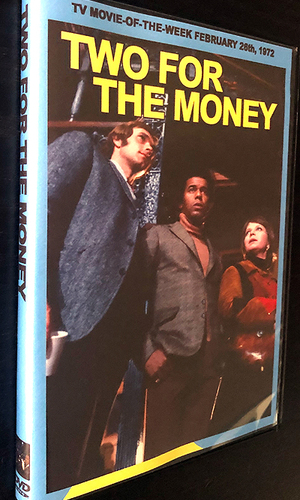

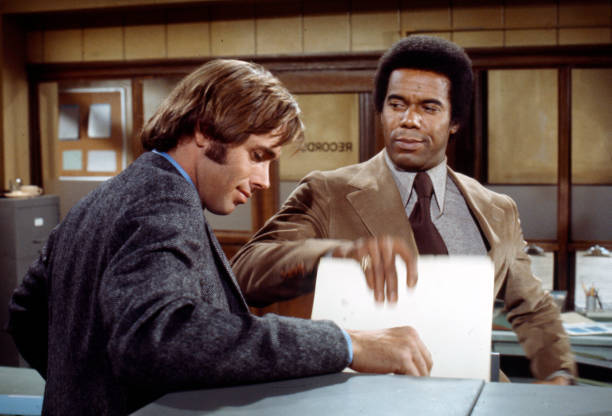

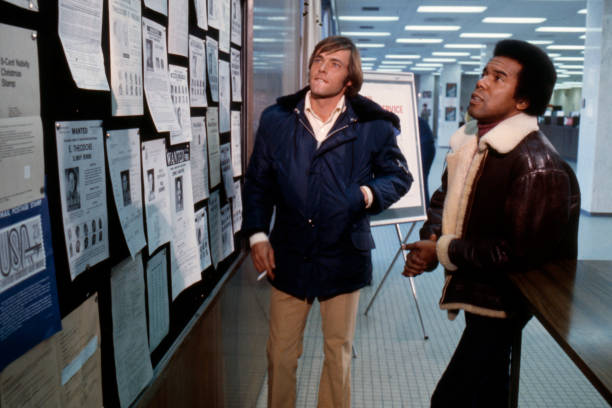

1972 Two for the Money (TV Movie)

Directed by Bernard L. Kowalski

Starring: Robert Hooks, Stephen Brooks, Walter Brennan, and Shelley Fabares

Unspecified – 1972: (L-R) Stephen Brooks, Robert Hooks appearing in the ABC tv movie ‘Two for the Money’. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

Unspecified – 1972: (L-R) Stephen Brooks, Robert Hooks, Michael Fox appearing in the ABC tv movie ‘Two for the Money’. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

Unspecified – 1972: (L-R) Stephen Brooks, Robert Hooks, Catherine Burns appearing in the ABC tv movie ‘Two for the Money‘. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

Unspecified – 1972: (L-R) Stephen Brooks, Robert Hooks appearing in the ABC tv movie ‘Two for the Money’. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

1971 Crosscurrent (TV Movie)

Inspector Lou Van Alsdale

1971 The Man and the City (TV Series)

– Run for Daylight (1971)

1971 Vanished (TV Movie)

Larry Storm

1970 The Bold Ones: The New Doctors (TV Series)

Scott Dayton

– Killer on the Loose (1970) … Scott Dayton

1970 The Mike Douglas Show(TV Series)

– Episode #9.159 (1970)

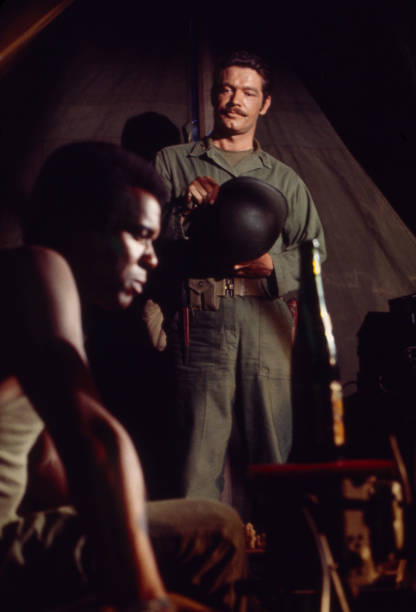

1970 Carter’s Army (TV Movie)

Lt. Edward Wallace

Unspecified – 1970: (L-R) Stephen Boyd, Robert Hooks appearing on the Walt Disney Television via Getty Images tv movie ‘Carter’s Army‘, January 27, 1970. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

Unspecified– 1970: (L-R) Glynn Turman, Robert Hooks appearing on the Walt Disney Television via Getty Images tv movie ‘Carter’s Army’, January 27, 1970. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

Unspecified– 1970: (L-R) Robert Hooks, Susan Oliver appearing on the Walt Disney Television via Getty Images tv movie ‘Carter’s Army’, January 27, 1970. (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

1970 The Last of the Mobile Hot Shots

Chicken

This is a scene from the Hollywood film “Last of the Mobile Hotshots” adapted from Tennessee Williams’ Broadway play “The Seven Descents of Myrtle.” And it is a tale about casting…in this case casting a white actor in a black/mixed-race role. The play is about two half-brothers. One white, the other Black, fighting over who rightfully owns the old plantation left by their family. When the play was produced on Broadway, the role of the Black brother was played by a white actor. This created total turmoil and pushback among Black actors and Black union organizations in New York, me among them, participating in daily and nightly boycotts and picket lines in front of the theater, forcing the play to eventually close down from racial pressures. Obviously, the demonstrations WORKED because when the play was adapted for the Hollywood film production, I was the Black actor who won the role of the Black brother in the story, James Coburn being the Caucasian brother. The brilliant – and racially aware – Sidney Lumet director of the upcoming film (ultimately retitled “Last of the Mobile Hotshots”) was resolved to give Tennessee Williams the true character that Broadway producers wouldn’t let him have. And I was the fortunate actor to get the role (Having performed on Broadway in Tennessee’s “The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Any More” opposite Tallulah Bankhead, it seemed rather fated.)

Just thinking about the amazing time shooting this Sidney Lumet film with James Coburn in the KKK regions of deep Louisiana in the early ’70s. A story about two brothers (one white, one Black) fighting for who owns the old family plantation left by the white father. One of Tennessee William’s early scripts about race issues! I…Just reflecting on my very diverse film career!… Sorry folks, the name of the film is “Last of the Mobile Hotshots”

Preview Clip: Last of the Mobile Hot Shots (1970, starring Robert Hooks)

1969 Then Came Bronson (TV Series)

Henry Tate

– A Long Trip to Yesterday (1969) … Henry Tate

1967-1969 N.Y.P.D. (TV Series)

Det. Jeff Ward

– No Day Trippers Need Apply (1969) … Det. Jeff Ward

– Everybody Loved Him (1969) … Det. Jeff Ward

– Boys Night Out (1969) … Det. Jeff Ward

– Face on the Dart Board (1969) … Det. Jeff Ward

– Who’s Got the Bundle? (1969) … Det. Jeff Ward

Show all 49 episodes

UNITED STATES – SEPTEMBER 05: N.Y.P.D. – gallery – 9/5/67, Robert Hooks (as Det. Jeff Ward), Frank Converse (as Det. Johnny Corso), Jack Warden (as Lt. Mike Haines) on the Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Television Network drama “N.Y.P.D”. The three detectives fight every kind of criminal all over New York City., (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

UNITED STATES – JANUARY 21: N.Y.P.D – “The Night Watch” – 1/21/69, Robert Hooks (as Det. Jeff Ward), Jack Warden (as Lt. Mike Haines), Frank Converse (as Det. Johnny Corso) on the Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Television Network drama “N.Y.P.D“. The three detectives fight every kind of criminal all over New York City., (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

“My very first starring role in a television series “NYPD”! It was the first network drama to ever star a Black actor and I thoroughly enjoyed all the national accolades from that historic fact! Here I am with my amazing co-stars Frank Converse next to me, and the great Jack Warden sitting. “NYPD” was shot almost entirely on the street of New York, and the stories were taken from the actual NYPD police files.“

UNITED STATES – FEBRUARY 11: N.Y.P.D. – “Candy Man” – 2/11/69, Candy (James Earl Jones), the director of a drug rehabilitation center, is questioned by Det. Ward (Robert Hooks) in this two-part episode of “N.Y.P.D.” on the Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Television Network., (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

UNITED STATES – OCTOBER 01: N.Y.P.D. – “Naked in the Streets” – 10/1/68, Susan Trustman (as Martha), Laurence Luckinbill (as Ed), Robert Hooks (as Det. Jeff Ward), Frank Converse (as Det. Johnny Corso) on the Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Television Network drama “N.Y.P.D“. The three detectives fight every kind of criminal all over New York City., (Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images Photo Archives/Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

1969 Mannix (TV Series)

Floyd Brown

– Last Rites for Miss Emma (1969) … Floyd Brown

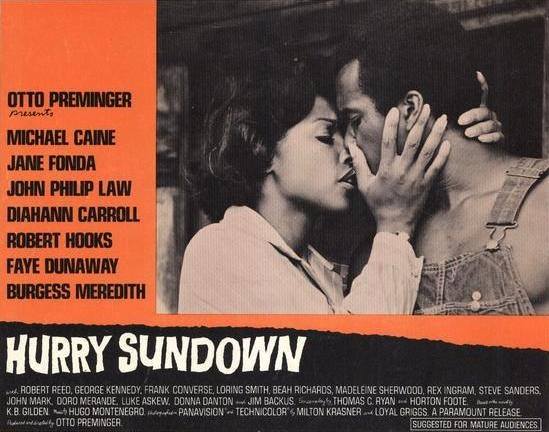

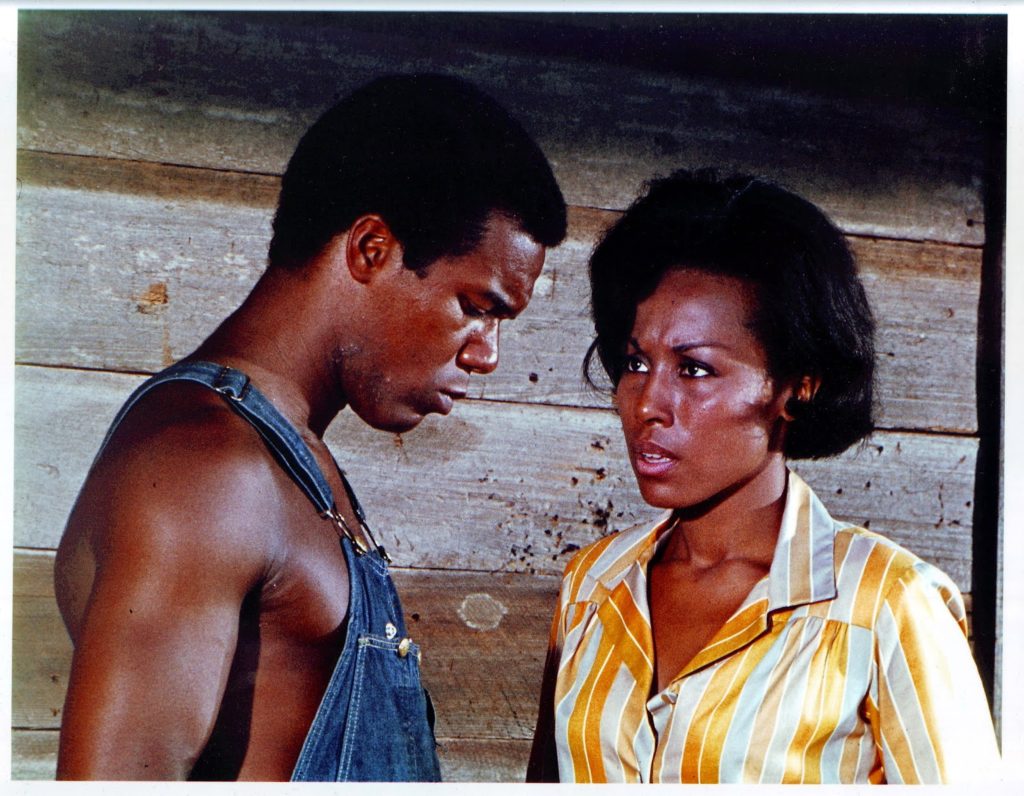

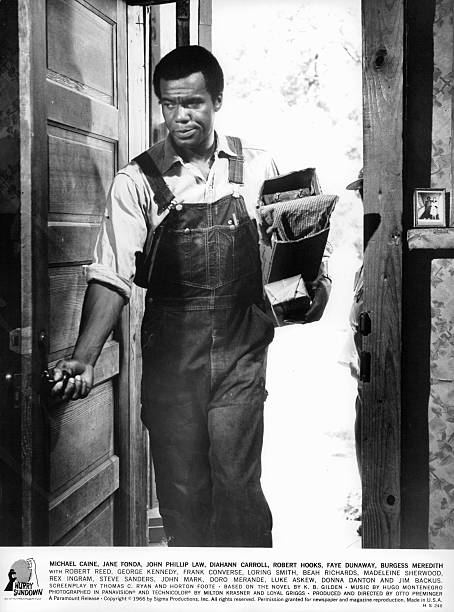

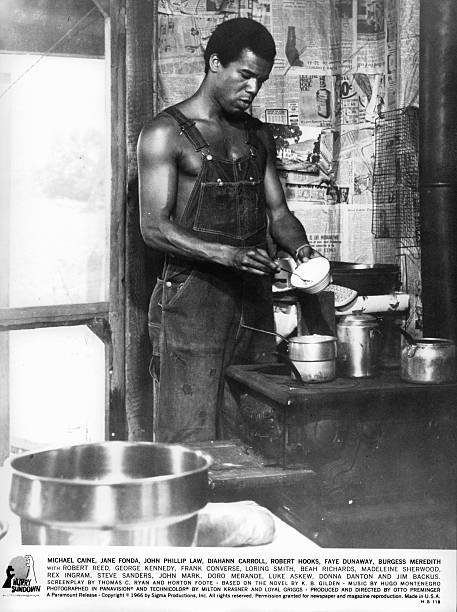

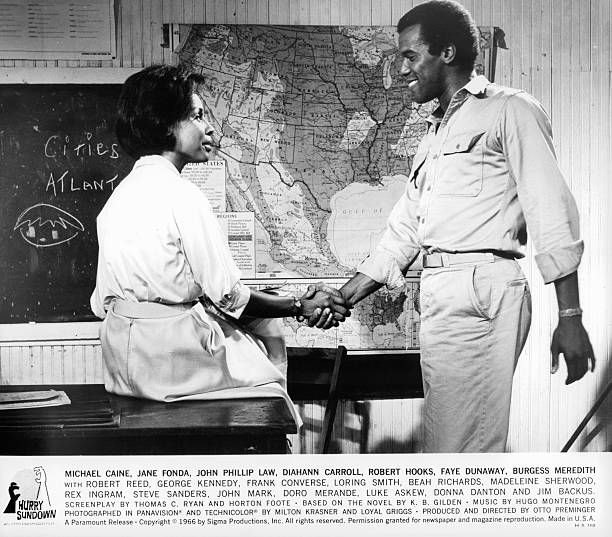

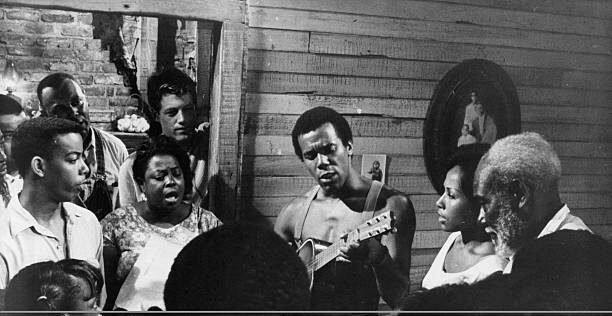

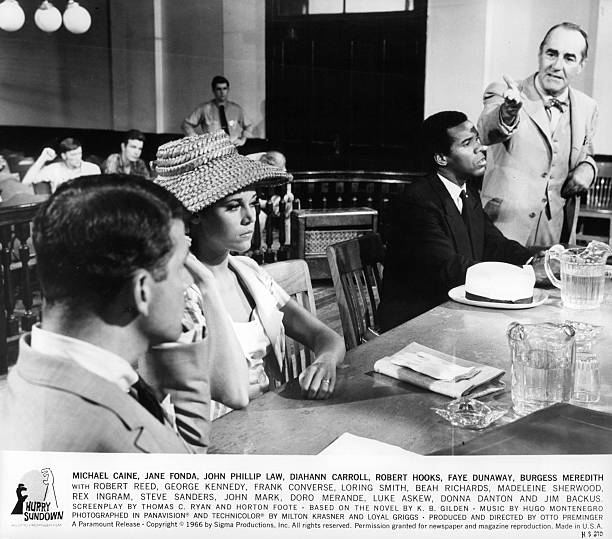

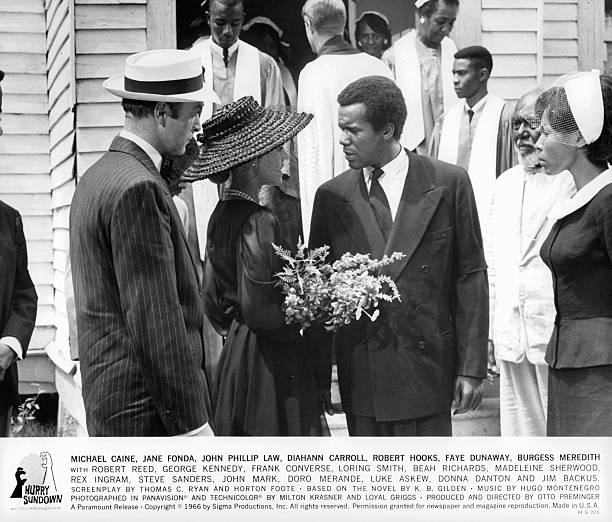

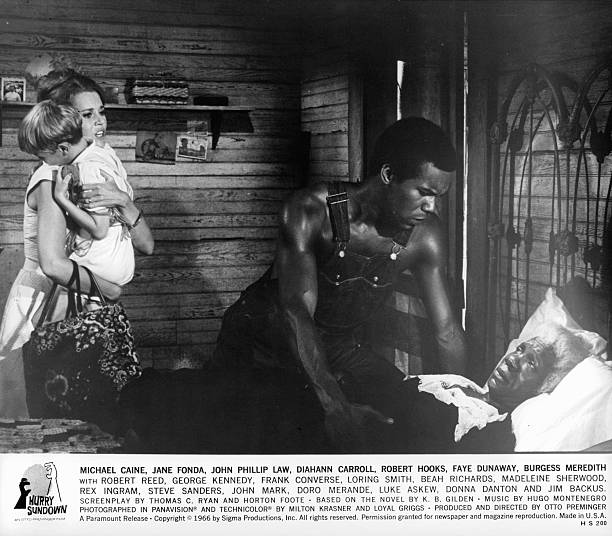

1967 Hurry Sundown

Reeve Scott

Here’s a classic throw-back photo of dear, wonderful and beautiful Diahann Carroll with yours truly (yes! we are eating face!) in a serious love scene from the Hollywood movie done ‘before its time’ “Hurry Sundown”. Boy! does the world miss this amazingly talented actress (and my dear friend and colleague!)

Robert Hooks walking in the door in a scene from the film ‘Hurry Sundown‘, 1966. (Photo by Paramount/Getty Images)

Robert Hooks in a kitchen cooking in a scene from the film ‘Hurry Sundown‘, 1966. (Photo by Paramount/Getty Images)

Robert Hooks and Diahann Carroll shaking hands in a scene from the film ‘Hurry Sundown’, 1966. (Photo by Paramount/Getty Images)

A crowd gathers as Robert Hooks plays the guitar in a scene from the film ‘Hurry Sundown‘, 1966. (Photo by Paramount/Getty Images)

Jane Fonda and Robert Hooks ignoring each other’s presence in a scene from the film ‘Hurry Sundown’, 1966. (Photo by Paramount/Getty Images)

Michael Caine, Jane Fonda, and Robert Hooks at a church gathering in a scene from the film ‘Hurry Sundown’, 1966. (Photo by Paramount/Getty Images)

Jane Fonda looks as Robert Hooks attends to sick, Beah Richards in a scene from the film ‘Hurry Sundown’, 1966. (Photo by Paramount/Getty Images)

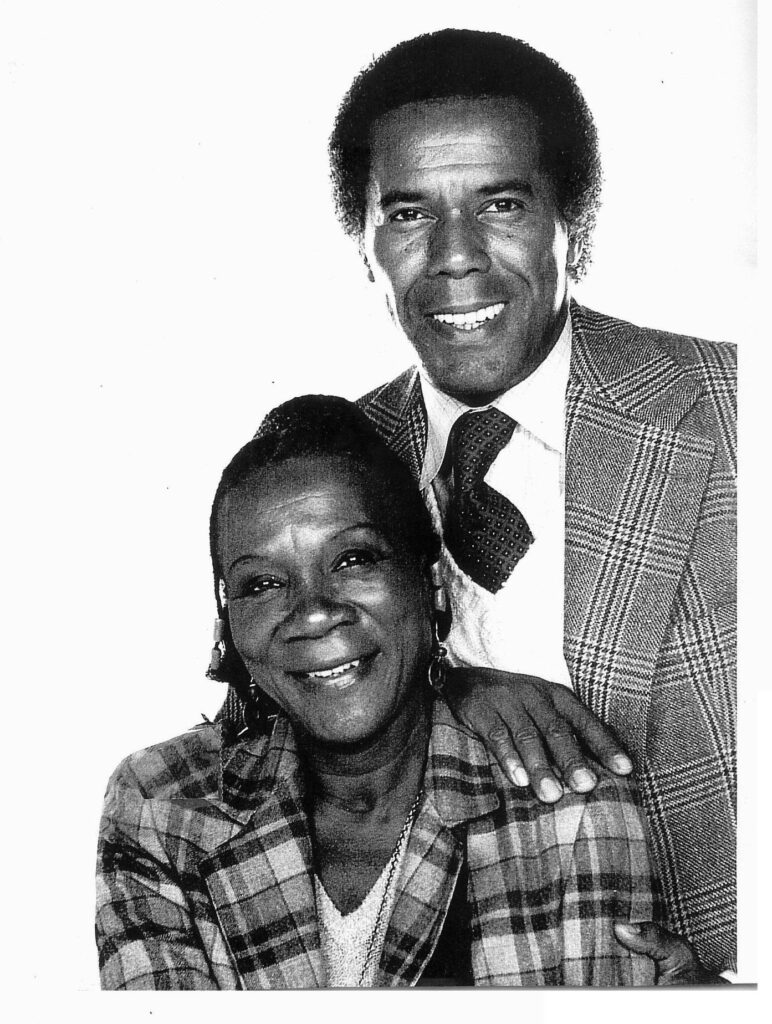

Me and the brilliant actress, writer, and legendary teacher Beah Richards. Here, on a press junket for the Otto Preminger feature film “Hurry Sundown” (circa 1967) where Beah plays my mother in the film!

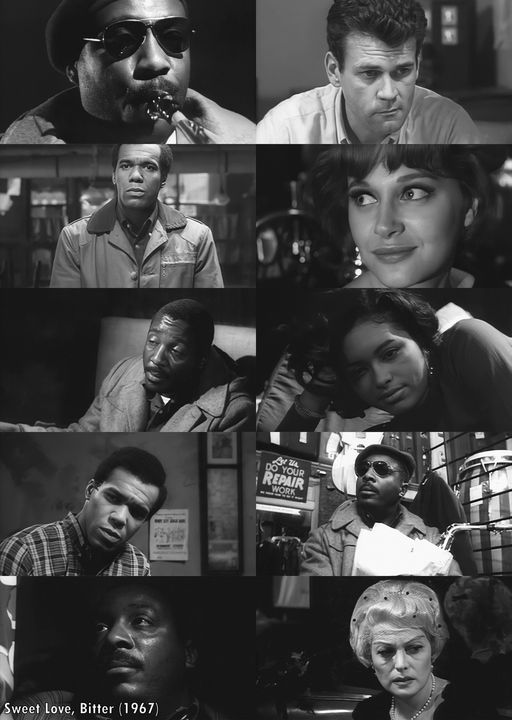

1967 Sweet Love, Bitter

Keel Robinson

“Sweet Love Bitter” – Dick Gregory and Don Murray

Sweet Love, Bitter (1967, starring Dick Gregory and Robert Hooks)

“Sweet Love, Bitter” (1967) is a drama film directed by Herbert Danska, who also co-wrote with Lewis Jacobs and Martin Kroll, who based the movie on the novel “Night Song” by John Alfred Williams. Williams was a Black American author, journalist, and academic known for his 1967 bestseller novel “The Man Who Cried I Am.” Charlie Parker’s life was the inspiration for the story of the film. Cast members include Dick Gregory, Robert Hooks, and Don Murray. This movie was the first movie credit for both Hooks and Gregory. However, Hooks had a career in theatre and was one of the founders of the Negro Ensemble Company, established in 1967. Dick Gregory, at the time, was a comedian and outspoken activist. Mal Waldron recorded the soundtrack for the film.

The movie touches on the interracial dating narrative that became popular in the 60s. It also explores the lives and struggles of Black jazz musicians within white society.

Director: Herbert Danska

Writers: John Alfred Williams, Herbert Danska, Lewis Jacobs, Martin Kroll

Starring Dick Gregory, Robert Hooks, Don Murray, Diane Varsi

Storyline

A Black jazz musician, Richie ‘Eagle’ Stokes (Dick Gregory), and a white professor, David Hillary (Don Murray), cross paths at a bar, where they bond and discuss where they are in life. Both gentlemen are in sorrow but in different ways. Stokes struggles with being Black in white society, and Hillary mourns the loss of his wife. Keel Robinson (Robert Hooks) offers Hillary a job at his bar, where Robinson reveals his interracial relationship with Della (Diane Varsi). However, Stokes’ abuse of alcohol and drugs becomes problematic not only for himself but also for those who support him.

https://www.daarac.ngo

Sweet Love, Bitter, tells the story of a fictional Jazz musician, loosely based on the life of CHARLIE PARKER, and the struggles of a Black musician in White America. With a score by MAL WALDRON. Stars Dick Gregory, Don Murray, Diane Varsi, et. al. An obscure indie film, originally released in 1967.

1966 Preview Tonight (TV Series)

– The Cliff Dwellers (1966)

1965 Profiles in Courage (TV Series)

Frederick Douglass

– Frederick Douglass (1965) … Frederick Douglass

Robert Hooks and Frederick O’Neal – Profiles In Courage (1965)

“Profiles in Courage” (circa 1965.) With the Mittie Lawrence as Mrs. Douglass.

1963 East Side/West Side (TV Series)

Detective Stern

– Age of Consent (1963) … Detective Stern (as Bobby Dean Hooks)

Soundtrack

1968 The 22nd Annual Tony Awards (TV Special) (performer: “Smile, Smile”)

2015 Tab Hunter Confidential (Documentary) (special thanks)

2010/I Salvation Road (Short) (special thanks)

Self (14 credits)

2011 Life After (TV Series)

Himself

– Antonio Fargas (2011) … Himself

2009 Jackson Five in Africa (Documentary)

Narrator

2009 Independent Lens (TV Series documentary)

– Adjust Your Color: The Truth of Petey Greene (2009)

2008 Adjust Your Color: The Truth of Petey Greene (Documentary)

Himself

2004 Macked, Hammered, Slaughtered and Shafted (Documentary)

Himself

2004 TV in Black: The First Fifty Years (Video documentary)

Himself

1986 Passion and Memory (TV Movie documentary)

Himself

1981 Ossie and Ruby! (TV Series)

Himself

– Episode dated 21 February 1981 (1981) … Himself

1974-1976 Black Journal(TV Series)

Himself / Himself – Guest Host

– Episode dated 22 February 1976 (1976) … Himself

– Episode dated 7 May 1974 (1974) … Himself – Guest Host

1969 The David Frost Show (TV Series)

Himself

– Episode #2.22 (1969) … Himself

1968-1969 The Mike Douglas Show (TV Series)

Himself – Actor / Himself

– Episode #8.195 (1969) … Himself – Actor

– Episode #7.102 (1968) … Himself

1969 The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson (TV Series)

Himself – Guest

– Episode dated 19 March 1969 (1969) … Himself – Guest

1968 The 22nd Annual Tony Awards (TV Special)

Himself – Nominee & Performer

1968 The Joey Bishop Show (TV Series)

Himself

– Episode #2.91 (1968) … Himself

Archive footage (1 credit)

1991 Preminger: Anatomy of a Filmmaker (Documentary)

actor ‘Hurry Sundown’ (uncredited)