Media Depictions of the Mammy Archetype

by Dale Ricardo Shields

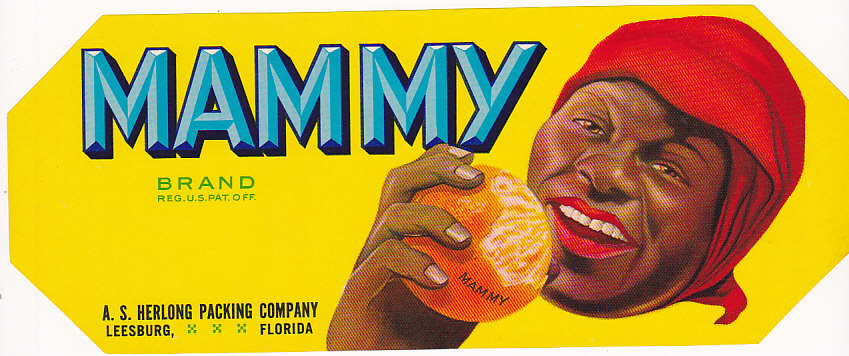

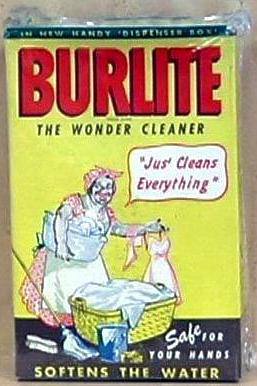

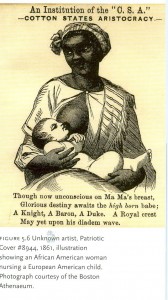

The Mammy archetype is one of the most notable Black stereotypes and caricatures which exist in American culture.

“In reality, the pancake mix was the creation of two White men in Missouri, and they named it after a character in a minstrel song, not an actual slave cook. Similarly, there is more folklore than fact underlying the stereotype of matronly slaves nursing young Whites. “I went in search of the mammy and couldn’t find her,” says historian Catherine Clinton, whose books include “Tara Revisited” and “Plantation Mistress”. “Most slaves who looked after White children were very young.” In other words, more like Prissy in Gone With the Wind than Mammy.

Or even younger. Harriet Tubman, for instance, was seven when she began caring for a baby and was whipped if the infant cried. Ex-slaves interviewed by the WPA in the 1930s also told of nursing babies as girls themselves, while the older black women of mammy lore looked after slave children whose mothers labored in the fields. These interviews also cast a harsh light on the supposedly privileged status of “house” slaves. One former slave recalled a “Mammy” being lashed “till de blood runned out”; another described a rape by the slaveowner’s sons. “I can tell you that a white man laid a nigger gal whenever he wanted,” said an ex-slave from Georgia who “went into the house as a waiting and nurse girl” between the ages of nine and twelve.” – The Atlantic

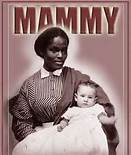

“Mauma Mollie. She died in the 1850s at the home of the white Florida family who enslaved her. A family member described her as nursing “nearly all of the children in the family” and said that they loved her as a “second mother“

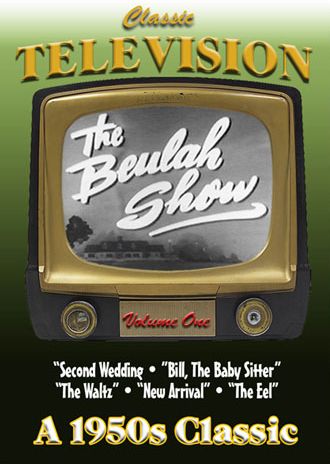

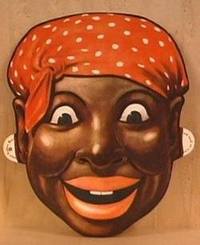

The Mammy, is generally characterized as masculine, overweight, sexually unattractive, large-breasted, non-threatening, and protective of their White families, but aggressive or hostile toward men; has been depicted in best-selling works of literature such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), on radio and television’s The Beulah Show (1934), and countless movies from D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915) to the recent film adaptation of Kathryn Stockett’s The Help (2009); and to a lesser known extent within historical Minstrel and Vaudeville shows.

The Beulah Show

The presence of Mammy was not only an important aspect of the White Southern home during later periods of, and increasingly after slavery, however the Mammy archetype is also responsible for having propelled and to some degree haunted the careers of many Black actresses.

Due to the racial tensions after slavery, the lack of desire to include Black women into the cinematic world of Hollywood, and overall lack of jobs for Black women, many Black actresses were limited to subservient roles on film and television. This often transpired into Black women playing domestic workers, and maintaining the stereotypical caricature of the Mammy role.

The role of the “Mammy” in the southern plantation household grew out of the role of the Negro slaves. Mammy was seen by Southerners as a way to create and maintain relationships with Blacks after slavery, and she was a vital aspect to maintaining the domestic sphere of the White household; it was not uncommon for Mammy to also take on the responsibility of rearing the offspring of her White family. When examining Mammy’s role and status within the White family structure, she could at times be seen as equal to that of the mistress of the home, because of her non-threatening and desexualized image. Mammy often gave orders to the White children and was also seen as a main source of protection to the family and for the home in the absence of the family. Due to Mammy’s semi-authoritative role within the White household, she and her family-husband and children if any were present; were given separate living quarters not too far off the main housing unit of the family she was serving.

The role of the “Mammy” in the southern plantation household grew out of the role of the Negro slaves. Mammy was seen by Southerners as a way to create and maintain relationships with Blacks after slavery, and she was a vital aspect to maintaining the domestic sphere of the White household; it was not uncommon for Mammy to also take on the responsibility of rearing the offspring of her White family. When examining Mammy’s role and status within the White family structure, she could at times be seen as equal to that of the mistress of the home, because of her non-threatening and desexualized image. Mammy often gave orders to the White children and was also seen as a main source of protection to the family and for the home in the absence of the family. Due to Mammy’s semi-authoritative role within the White household, she and her family-husband and children if any were present; were given separate living quarters not too far off the main housing unit of the family she was serving.

Although it may seem that the role of Mammy was more dignified compared to other servants, any social status achieved was diminished by her subservient domestic duties. Mammy’s often worked long hours to ensure the social and domestic stability of her master’s family, which often consequentially resulted in the neglect of her own family. Given this factor, Blacks viewed the role of the Mammy as a form of cultural transgression for the Black race but unfortunately were unable to transcend the Mammy image, as Black women sought out work in the post-slavery era and as they became more visible in American cinematic culture. Although the Mammy archetype is most notable in visual media, one of the earliest mentions of a Mammy figure transpired from a literary character within Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Although it may seem that the role of Mammy was more dignified compared to other servants, any social status achieved was diminished by her subservient domestic duties. Mammy’s often worked long hours to ensure the social and domestic stability of her master’s family, which often consequentially resulted in the neglect of her own family. Given this factor, Blacks viewed the role of the Mammy as a form of cultural transgression for the Black race but unfortunately were unable to transcend the Mammy image, as Black women sought out work in the post-slavery era and as they became more visible in American cinematic culture. Although the Mammy archetype is most notable in visual media, one of the earliest mentions of a Mammy figure transpired from a literary character within Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

In Stowe’s novel, Aunt Chloe was the mammy figure, who was responsible for the domestic duties of the Shelby household; and often struggled internally with complex issues about her role as a domestic servant and slavery. Aunt Chloe was described as many Mammy figures have been throughout history, nurturing and protective of “her” White family, but less caring toward her own children. She is the prototypical fictional mammy: self-sacrificing, White-identified, fat, asexual, good-humored, a loyal cook, housekeeper, and quasi-family member.

A round, black, shiny face is hers, so glossy as to suggest the idea that she might have been washed over with the whites of eggs, like one of her own tea rusks. Her whole plump countenance beams with satisfaction and contentment from under a well-starched checkered turban, bearing on it; however, if we must confess it, a little of that tinge of self-consciousness which becomes the first cook of the neighborhood, as Aunt Chloe was universally held and acknowledged to be.