Marion Hurt

Marlon Hurt

(Actor)

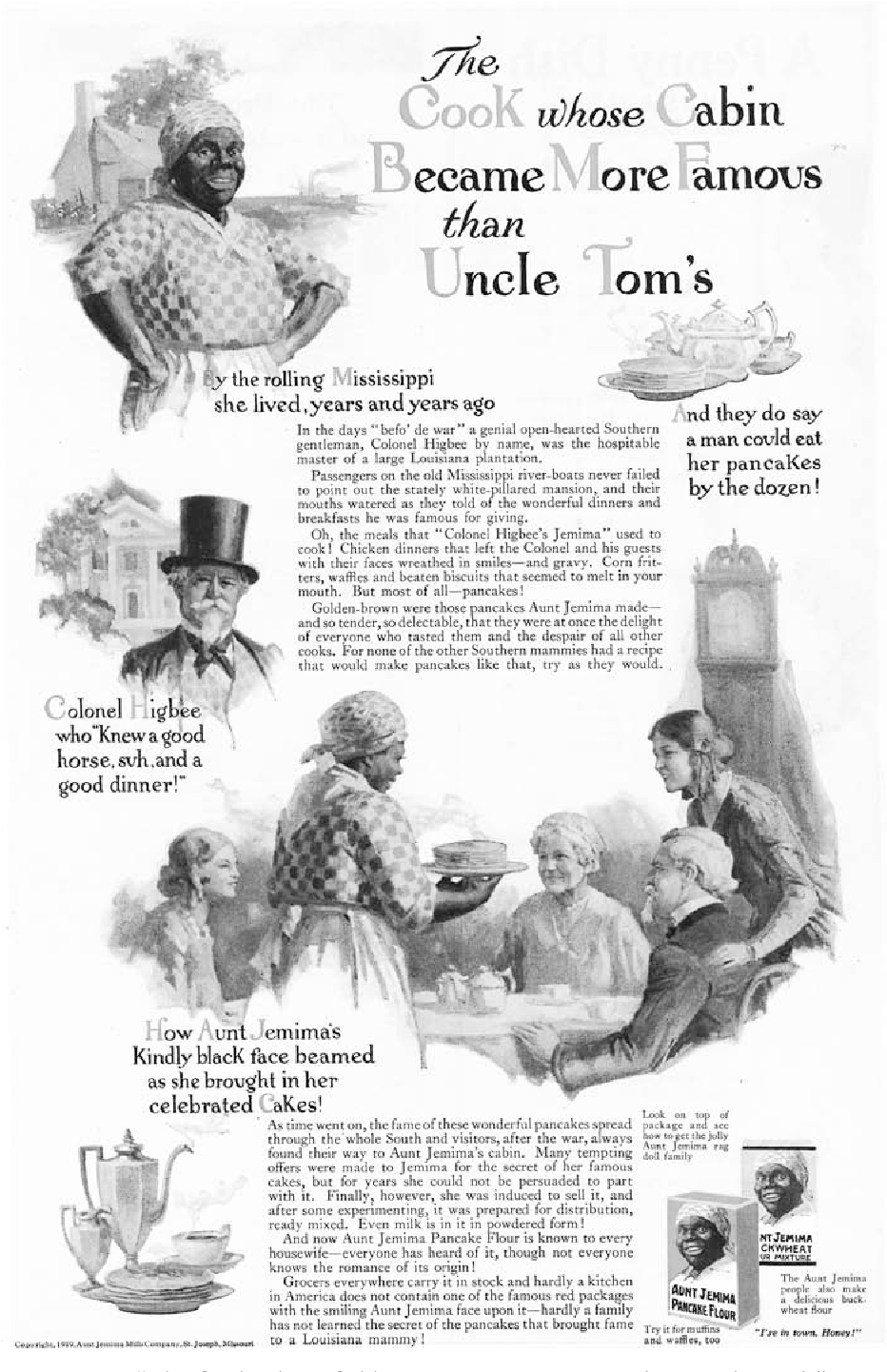

Marlin Hurt (1905-1946), was an American stage entertainer and radio actor. It is believed that Hurt’s inspiration for the Beulah’s voice was an African-American woman named Mary who was Hurt’s family Mammy. After Hurt appeared on several radio programs using a ‘Black’ dialectical voice, the Beulah show was eventually given its own platform in 1943. Although Hurt brought the voice of Beulah to critical acclaim, his tenure on the radio series as the voice of Beulah was short-lived due to his untimely death in 1946; near the end of the first season of the series.

Following Hurt’s death and keeping in line with the previous voicing of Black dialects by White actors, Beulah was then voiced by another White actor by the name of Bob Corley; at which time the show was once again renamed to The Beulah Show.

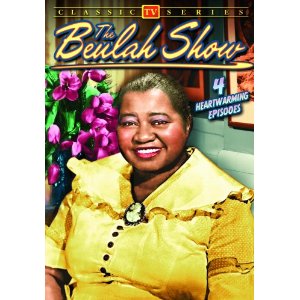

Corley remained the voice of Beulah until November 24, 1947, when notable Black actress Hattie McDaniel took over the radio show earning $1000 a week, and eventually negotiated $2000 a week.

McDaniel garnered the highest ratings for the show than previously earned by both Hurt and Corley. McDaniel later appeared on six episodes in the second season of the television adaptation of The Beulah Show in 1951 but was replaced by actress Lillian Randolph after falling ill.

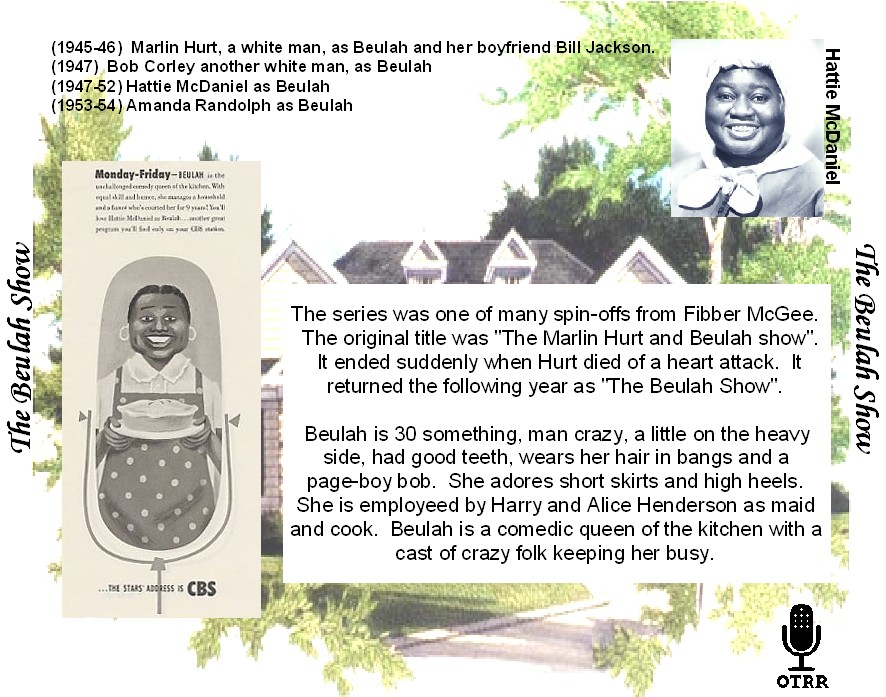

Lillian Randolph

Lillian Randolph was a 20th Century actress who routinely, yet proudly, presented the role of the Black domestic in film and radio and defended her right to maintain such characters in an intelligent fashion for much of her career. Randolph was born in Knoxville, Tennessee in 1915. She first entered the world of entertainment as a singer at WJR Radio in Detroit in the early 1930s.

In 1936, Randolph migrated to Los Angeles and made her debut as a singer at the Club Alabam. Five years later, she landed the role of the maid, Birdie, on the radio and TV series The Great Gildersleeve, and soon became one of the most sought after Black actresses of the period. Randolph portrayed Birdie until 1957. She simultaneously played the role of Daisy, the housekeeper on The Billie Burke (radio) situation comedy from 1943 to 1946, and title role of the radio show Beulah in the early 1950s when Hattie McDaniel became ill. Also in the early 1950s she performed on the Amos n’ Andy show, recreating the role of Madame Queen, which she first played on the radio version of the series.

In 1946, Randolph and Sam Moore, one of the script writers of The Great Gildersleeve program, published a rebuttal to those critics in Ebony magazine. Randolph defended her role as the character Birdie, reminding Ebony‘s readers that the show’s writers had never written dialect into the script and were particularly careful not as not to offend Black viewers. Randolph valued the benefits that such parts brought to her career and fought to protect the availability of roles from the efforts of those protesting anti-stereotypical roles in film and radio.

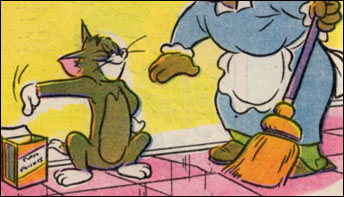

In the early 1960s, Randolph spent several years coaching drama and resumed her singing and acting careers. For more than a decade, she also supplied the voice of the cook, Mammy two-shoes, in the Tom and Jerry cartoon series.

Mammy Two Shoes is a fictional character in MGM’s Tom and Jerry cartoons. She is a heavy-set middle-aged African American woman who is the housemaid in the house which Tom and Jerry reside. But the fact that she has her own bedroom in the short “Sleepy Tom” raises the possibility of her being the owner of the house, as no other human is present in the house in shorts she appears. She would scold and attack Tom whenever she believed he was misbehaving; Jerry would sometimes be the cause of Tom’s getting in trouble. As a partially-seen character, her head was rarely seen, except in a few cartoons including Part Time Pal (1947), A Mouse in the House (1947), Mouse Cleaning (1948), and Saturday Evening Puss (1950). Mammy appeared in 19 cartoons, from Puss Gets the Boot (1940) to Push-Button Kitty (1952). Mammy’s appearances have often been edited out, dubbed, or re-animated in later television showings, since her character is an archetype now usually considered racist. Her creation points to the ubiquity of the “mammy” stereotype in American popular culture, and the character was removed from the series after 1953 due to protests from the NAACP.

Although she repeatedly received several complaints from the NAACP and Black community activists who complained about her racially stereotypical roles, Randolph maintained her right to portray such characters as Madame Queen, Birdie, and as the voice of the cook on the popular Hanna-Barbera cartoon Tom and Jerry despite public opposition.

Mammy Two Shoes in a scene from the Tom & Jerry short Saturday Evening Puss. This is the only time her facial features are clearly seen, albeit for only a few frames.

["Tom and Jerry is an American animated media franchise and series of comedy short films created in 1940 by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera. Best known for its 161 theatrical short films by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the series centers on the rivalry between the titular characters of a cat named Tom and a mouse named Jerry. Wikipedia Owner: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer; (1940–1986); Turner Entertainment; (Warner Bros. Discovery; 1986–present)"]

By the 1970s, Randolph had made more than 75 film and television appearances and reached a career that spanned more than decades. Lillian Randolph died of cancer in 1980 in Los Angeles, California.

Hattie McDaniel

VIVIEN LEIGH and HATTIE McDANIEL in “Gone With the Wind” (1939)

“I’d rather play a maid and make $700 a week

than be a maid and make $7.”

Hattie McDaniel

Biography

By Richard Harland Smith

Actress Hattie McDaniel (1895-1952)

Actress Hattie McDaniel (1895-1952)

Hattie McDaniel born June 10, 1895, was one of the best-known Black American actresses of the 20th Century. McDaniel, like many Black actresses of her time period, often struggled to gain television and film roles outside of the subservient role of the Mammy.

Gone with the Wind (1934)

Hattie McDaniel (Mammy)

Gone with the Wind

McDaniel had played the Mammy figure in many of her prior films, but her role in Gone with the Wind was pivotal due to her being the first Black actress to acquire an Academy Award nomination and win for her portrayal of “Mammy” in the film, and the personal connection she made with the character.

McDaniel stated that she understood Mammy, because her own grandmother had worked on a plantation in a similar role. McDaniel was widely praised for her success and simultaneously received massive criticism for her continued participation in maintaining the lifeline of the Mammy caricature. The harshest criticism of McDaniel’s role in the film was from the N.A.A.C.P. The N.A.A.C.P felt that McDaniel was creating a counterproductive dialogue through her continued acceptance of subservient cinematic roles in a time period when they were fighting for racial equality. In response to her critics, McDaniel was quoted to have said: “Why should I complain about making seven thousand dollars a week playing a maid? If I didn’t, I’d be making seven dollars a week actually being one.”

McDaniel stated that she understood Mammy, because her own grandmother had worked on a plantation in a similar role. McDaniel was widely praised for her success and simultaneously received massive criticism for her continued participation in maintaining the lifeline of the Mammy caricature. The harshest criticism of McDaniel’s role in the film was from the N.A.A.C.P. The N.A.A.C.P felt that McDaniel was creating a counterproductive dialogue through her continued acceptance of subservient cinematic roles in a time period when they were fighting for racial equality. In response to her critics, McDaniel was quoted to have said: “Why should I complain about making seven thousand dollars a week playing a maid? If I didn’t, I’d be making seven dollars a week actually being one.”

In addition to McDaniel’s personal detractors, the film itself received numerous amounts of criticism from the Black press and the Black community. Objections of the film ranged from the whimsical use of the word “nigger and the overall negative representation of Black culture and its people. Although both McDaniel and the film received their share of praise and criticism, the role of Mammy, played by McDaniel, was said to have helped shape the future respect of performances for Black actresses- including McDaniel’s co-star Butterfly McQueen.

Thelma “Butterfly” McQueen

(January 7, 1911 – December 22, 1995) was an American actress. Originally a dancer, McQueen first appeared as Prissy, Scarlett O’Hara’s maid in the 1939 film Gone with the Wind. She continued as an actress in film in the 1940s, then moving to television acting in the 1950s.”

Butterfly McQueen

Gone with the Wind

“Thelma “Butterfly” McQueen was born in Tampa, Florida on January 8, 1911. Her father, Wallace McQueen, worked as a stevedore and her mother, Mary Richardson, was a housekeeper and domestic worker. After McQueen’s parents separated, her mother moved from job to job and McQueen lived in several cities on the East Coast before settling in Augusta, Georgia. As a young teen, McQueen moved to Harlem, New York, where her mother worked as a cook.

McQueen enrolled in the Lincoln Training School for Nursing in the Bronx before pursuing an acting career. She joined Venezula Jones’s Youth Theatre Group in Harlem and performed in the Group’s 1935 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As a result of her role in the production’s “Butterfly Ballet,” she adopted “Butterfly” as her stage name. In 1937, McQueen debuted on Broadway in Brown Sugar. She also appeared in What a Life (1938) and the Benny Goodman and Louis Armstrong musical, Swingin the Dream (1939).

Butterfly McQueen as Puck, Maxine Sullivan as Titania and Louis Armstrong as Bottom/Pyramus in the Broadway production of “Swingin’ the Dream,” a jazz musical that has been largely forgotten.Credit…Vandamm Studio/The New York Public Library, via Museum of the City of New York

McQueen received her big break in Hollywood when David O. Selznick cast the 28-year-old actor as Prissy in Gone with the Wind (1939). McQueen’s role as Prissy brought her national fame and it remains her most remembered performance.

For the next ten years, McQueen continued to work in film, television, and radio. As a result of the limited roles available to African American women in the entertainment industry, McQueen frequently was cast as the maid. Her film work included The Women (1939), Cabin in the Sky (1943), I Dood It! (1943), Mildred Pierce (1945), and Killer Diller (1948) among others. She worked in radio on the Jack Benny Show and on Beulah, which became a television show in 1950.

Unable to support herself as an actress, McQueen worked in a wide-range of occupations, including as a restaurant owner, paid companion, waitress, tour guide, Macy’s toy department employee, cab dispatcher, music and dance teacher, radio show host, and factory worker. She temporarily moved back to Augusta, Georgia for employment in the 1960s. By the end of the decade, she returned to Harlem where she worked as a receptionist and dance teacher at Mount Morris Park Recreation Center. In the 1970s, McQueen enrolled at the City College of New York where she earned a degree in political science.

McQueen continued to perform on screen and stage sporadically. She appeared in three films in the 1970s and 1980s, including Mosquito Coast (1986). She won a Golden Globe and Emmy Award for her performance in Seven Wishes of Joanna Peabody (1978).

In 1989, McQueen participated in the 50th anniversary celebration for Gone with the Wind. In 1995, a kerosene fire burned down her Augusta, Georgia home and McQueen received severe burns. She died from her injuries on December 22, 1995.”

Granshaw, M. (2010, August 31). Thelma “Butterfly” McQueen (1911-1995). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/mcqueen-thelma-butterfly-1911-1995/SOURCE OF THE AUTHOR’S INFORMATION:

Stephen Bourne, Butterfly McQueen Remembered (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow

Press, 2008); Axel Nissen, Actresses of a Certain Character (Jefferson,

NC: McFarland and Company, 2007); Dwandalyn R. Reece, “Butterfly

McQueen,” in African American National Biography, vol. 5, eds. Henry

Louis Gates, Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2008).

Ms. McDaniel and Ms. McQueen were both at the height of their careers during their appearance in Gone with the Wind, but they were only two out of several Black actresses who were making strides in the film industry; all nonetheless as Mammy caricatures. Most closely related to the skill and talent of Ms. McDaniel was that of Ms. Louise Beavers.

Ms. Louise Beavers and Ms. Hattie McDaniel