The Mammy Archetype: A Black Maiden Syndrome

- By iforcolor in Actress, History, Vaudeville

-

November 4, 2020

Louise Beavers

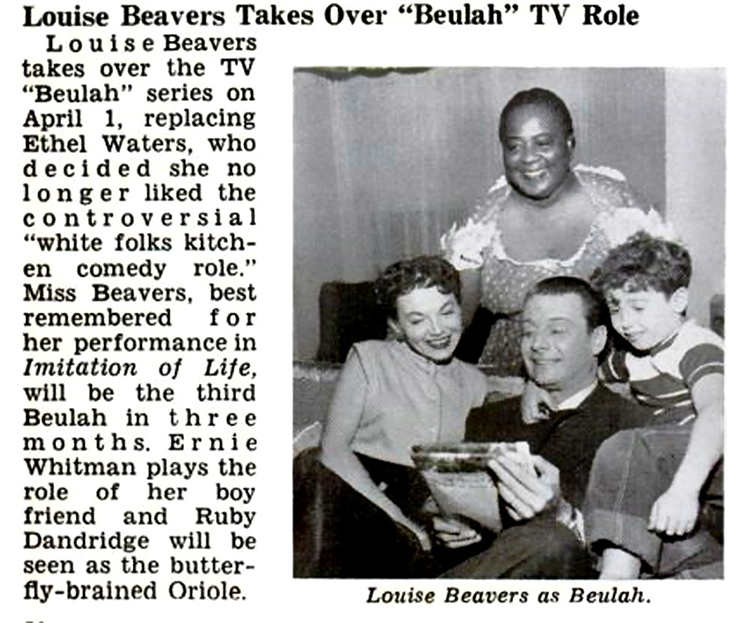

Prior to Hattie McDaniel’s success in GWTW, another well-known actress during the time period was Louise Beavers. Louise Beavers, born March 8, 1902, was a Black American stage, television, and film actress; is noted to possibly have been a descendant of President James Monroe. Louise Beavers began her acting career in the 1920s, performing with the Lady Minstrels– a group of young women who staged amateur productions and appeared on stage at the Loews State Theatre.

“Louise Beavers (March 8, 1902 – October 26, 1962) was an African-American film and television actress. Beavers appeared in dozens of films from the 1920s until 1960, most often in the role of a maid, servant, or slave. A native of Cincinnati, Ohio. Louise Beavers was a breakthrough actress for African Americans. Beavers became known as a symbol of a “mammy” on the screen. A mammy archetype “is the portrayal within a narrative framework or other imagery of a domestic servant of African descent, generally good-natured, often overweight, and loud”.[” –

Louise Beavers

Beavers begin her film career in 1927 and like those before her-most notably Hattie McDaniel; Louise Beavers was often cast for the Mammy role in her films. It is initially stated that Beavers rejected the casting call for a role in the film adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin three times before finally accepting the role, “because of the African roles given to colored people.”

Beavers acclaim in the 1920s was through her role as Julia in the 1929 film Coquette.

Louise Beavers with Mary Pickford in COQUETTE(’29)

Louise Beavers as Julia in Coquette (1929)

Louise Beavers and Carole Lombard in Made For Each Other

It is believed that this role established Beavers as a prominent African-American actress within the mainstream industry. Because of Beavers’ stature and dialectical voice, she soon became known as the actress to play the Mammy roles.

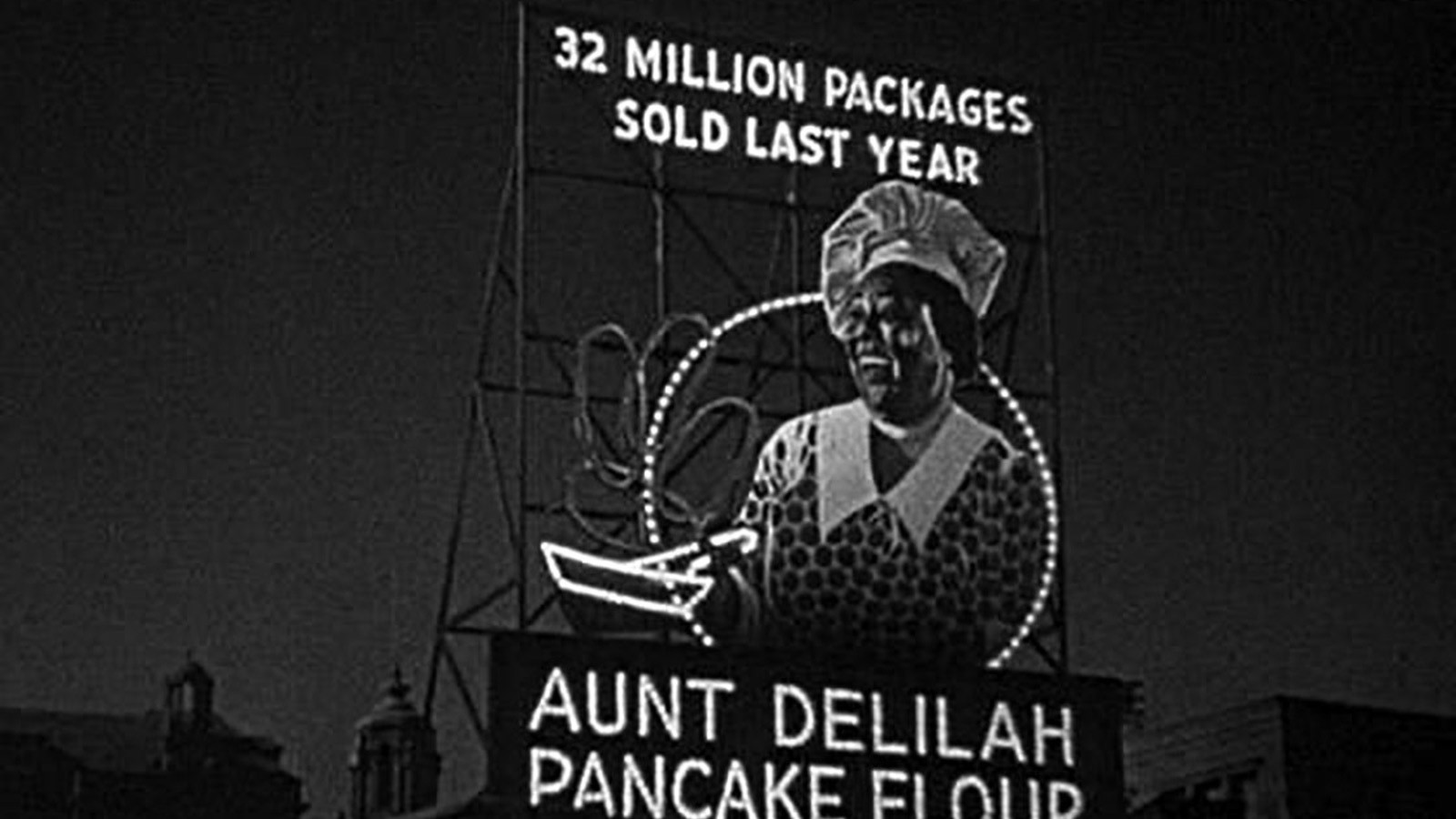

Beavers’ best-known role was that of Aunt Delilah in Imitation of Life (1934).

Imitation of Life

1934 American drama film directed by John M. Stahl. The screenplay by William Hurlbut, based on Fannie Hurst’s 1933 novel of the same name, was augmented by eight additional uncredited writers, including Preston Sturges and Finley Peter Dunne. The film stars Claudette Colbert, Louise Beavers, Warren William, Rochelle Hudson, and Fredi Washington.

Fredi Washington and Louis Beavers in “Imitation of Life” 1934

The film was originally released by Universal Pictures on November 26, 1934, and re-released in 1936. A 1959 remake of the same title was directed by Douglas Sirk.

This role transformed Beavers from a supporting actress; which she had previously played for White actresses, into the star of her films. Imitation of Life detailed the story of a Black maid played by Beavers, who inherits a pancake recipe. This movie’s mammy gave the valuable recipe to Miss Bea, her boss. Miss Bea successfully marketed the recipe and she offered Aunt Delilah a twenty percent interest in the pancake company.

The themes of the film, to the modern eye, deal with very important issues—passing, the role of skin color in the black community and tensions between its light-skinned and dark-skinned members, the role of Black servants in White families, and maternal affection.

Some scenes seem to have been filmed to highlight the fundamental unfairness of Delilah’s social position—for example, while living in Bea’s fabulous NYC mansion, Delilah descends down the shadowy stairs to the basement where her rooms are. Bea, dressed in the height of fashion, floats up the stairs to her rooms, whose luxury was built from the success of Delilah’s recipe.

Others highlight the similarities between the two mothers, both of whom adore their daughters and are brought to grief by the younger women’s actions. Some scenes seem to mock Delilah, because of her supposed ignorance about her financial interests and her willingness to be in a support role, but the two women have built an independent business together. In dying and in death—especially with the long processional portraying a very dignified African-American community—Delilah is treated with great respect.

IMITATION OF LIFE, Louise Beavers, Claudette Colbert, 1934

According to Jean-Pierre Coursodon in his essay on John M. Stahl in American Directors,

Fredi Washington … reportedly received a great deal of mail from young Blacks thanking her for having expressed their intimate concerns and contradictions so well. One may add that Stahl’s film was somewhat unique in its casting of a Black actress in this kind of part – which was to become a Hollywood stereotype of sorts.

Later films dealing with mulatto women, including the 1959 remake of Imitation of Life, often cast White women in the roles.

It was adapted into two films, the first of which came out in 1934, starring Claudette Colbert and Louise Beavers, and the second of which came out in 1959, starring Lana Turner and Juanita Moore.

They’re both very good films in their own right.

Delilah (Louise Beavers) – Annie (Juanita Moore)

Peola (Fredi Washington) – Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner)

“Co-star Fredi Washington told film historian Donald Bogle, “the one thing that happened with Louise was that her agents immediately, when she made such a hit in the picture, upped her salary beyond what anyone was going to pay for the type roles they had for her. I told her at the time, I just don’t think this is wise. But of course, they were her agents.”

Beavers continued her busy career after Imitation of Life, but unlike other actors who enjoyed a breakout success, there would be no opportunity for Louise Beavers to follow with another signature role. She was the most popular and successful Black actress of this time, but there wasn’t anything to play except a long line of maid roles.”

Ruby Dandrige

Although McDaniel had previously garnered critical acclaim for her voicing of and appearance on The Beulah Show; as Beulah Brown- with co-star Ruby Dandridge (Mother of screen star Dorothy Dandrige), McDaniel was present in many films throughout her career in the 1920s and 1930s.

- Abbey Lincoln, Al Jolson, Amanda Randolph, Anna Robinson, Barbara Stanwyck, Beau Bridges, Bette Davis, Bob Corley, Butterfly McQueen, Cicely Tyson, Clark Gable, Claudia McNeil, D.W. Griffith, David O. Selznick, Diahann Carroll, Dorothy Dandrige, Edith Wilson, Estelle Evans, Esther Rolle, Ethel Waters, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Hattie McDaniel, Ida B. Wells, Jean Harlow, Jennie Lee, John Kenrick, Kathryn Stockett, Lauri Peters, Lillian Randolph, Louis Armstrong, Louise Beavers, Marla Gibbs, Marlon Hurt, Maxine Sullivan, Nan Martin, Nancy Green, Nell Carter, Octavia Spencer, Oprah Winfrey, Otis McDaniel, Rosie Lee Moore Hall, Ruby Dandridge, Sanaa Lathan, Shirley Temple, Sidney Poitier, Theresa Harris, Viola Davis, Virginia Capers, Vivien Leigh, Whoopi Goldberg, William Hanna

iforcolor

ARCHIVIST, EDUCATOR, HISTORIAN, and ARTiST

Dale Ricardo Shields is a 2017 winner of The Kennedy Center/Stephen Sondheim Inspirational Teacher Award®, 2017 and 2015 Tony® award nominee for the Excellence in Theatre Education Award, the 2017 AUDELCO/"VIV" Special Achievement Award, 2020, 2021, and 2022 ENCORE AWARD / The Actors Fund and winner of the 2022.

Recently, he won the 2022 Legend Award from his alma mater Ohio University.

He is the 2021 winner of the Paul Robeson Award, presented (jointly) by the Actors Equity Association and the Actors Equity Foundation.

Research Accomplishments:

His extensive professional credits as a Director, Stage manager, and Actor (Broadway, Off-Broadway, Off-Off-Broadway, and Regional) As an actor he has appeared on Saturday Night Live, Another World, Guiding Light, The Cosby Show, and the ITV television series "Special Needs" and commercials and film.

Professor Shields is a member of the Actors Equity Association, Screen Actors Guild, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, and the American Guild of Musical Artists performance unions and an associate member of the Society of Stage Directors and Choreographers.

He began his artistic academic career in New York City at Playwrights Horizon, The South Bronx Action Theatre, and Mind Builders, and then was invited to join the teaching staff at the Joseph Papp Public Theatre (New York Shakespeare Festival). He represented the United States for Theatre Young Audiences at the ASSITEJ Theatre Festival in London, England.

He has been a Professor and Visiting Artist at Ohio University, The College of Wooster, Denison University, Macalester College, Randolph- Macon College, Susquehanna University, and SUNY Potsdam.

He holds B.F.A and M.F.A, Degrees from Ohio University.

Website(s)

Iforcolor.org [Research]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dale_Ricardo_Shields [Career]