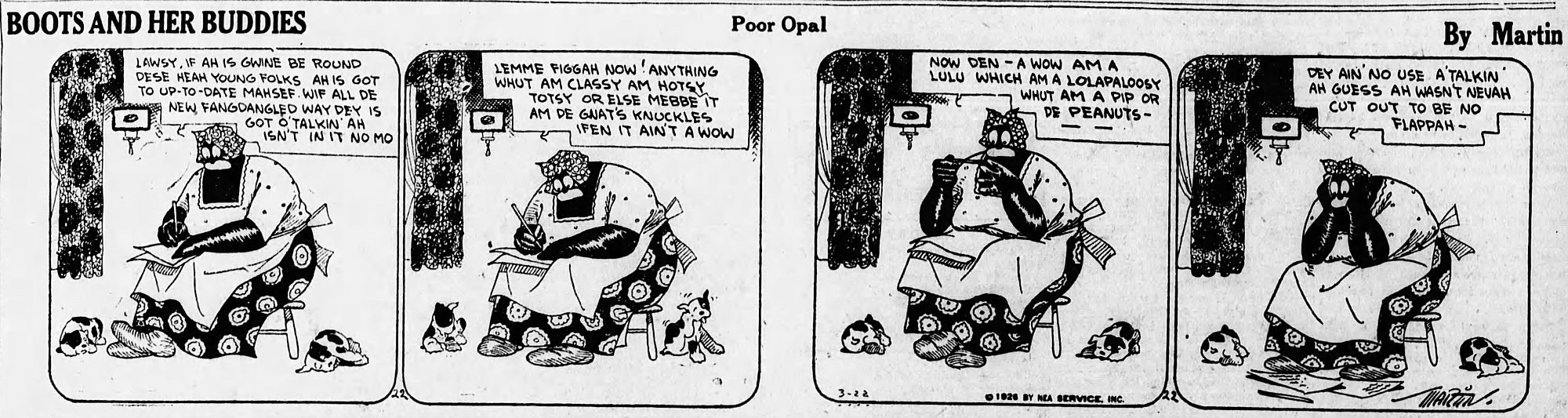

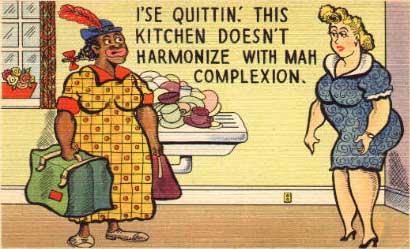

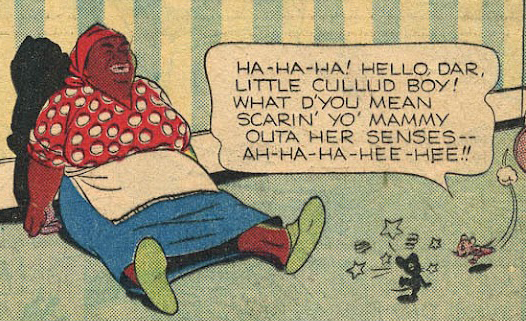

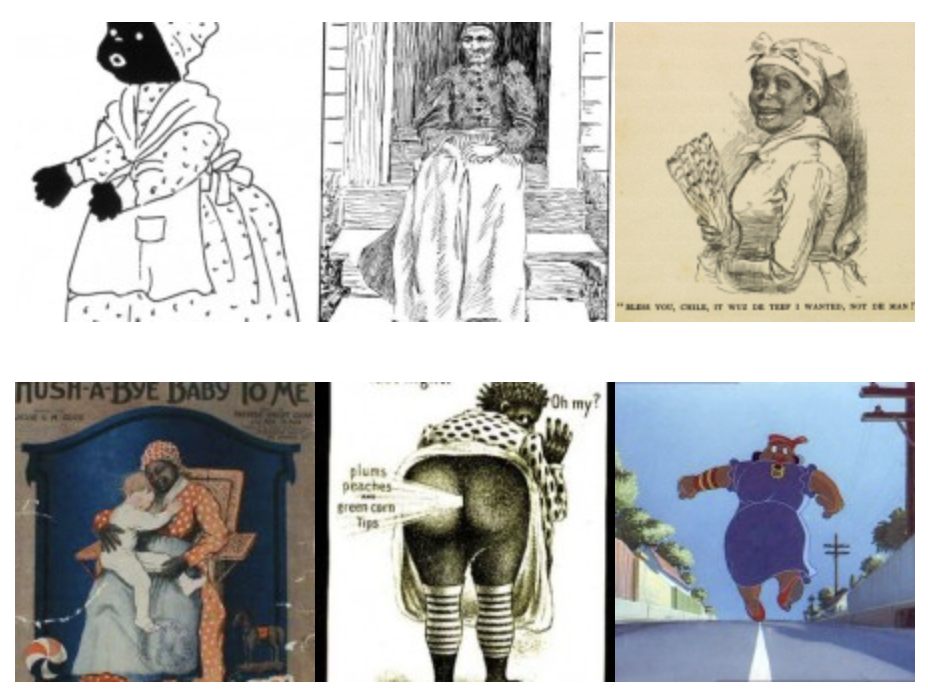

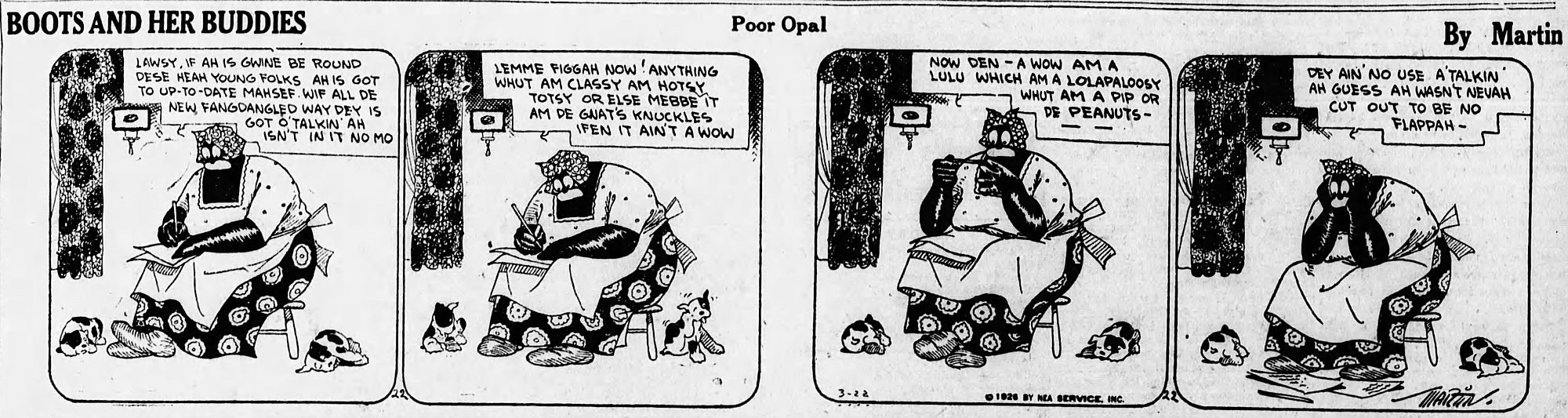

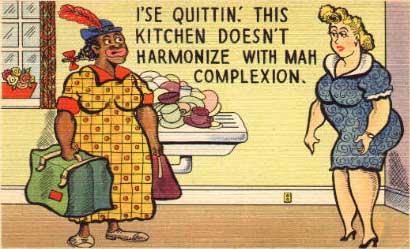

The Introduction of comic strips in the American press in the 1890’s corresponds with the beginning of a renewed of racial segregation in the United States.

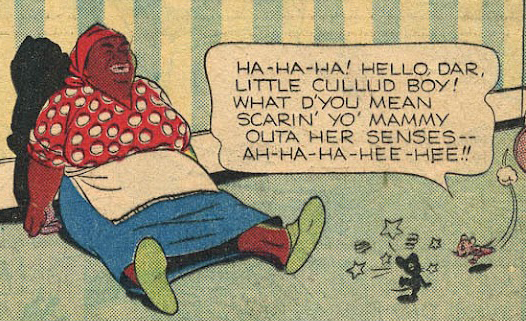

“While Southern laws were used to oppress American citizens of African descent, the mainstream white press served up accounts of Blacks in newspaper articles which supported such sanctions’. In the comics section, Blacks were the principal comic figures, having surpassed the Irish at the turn of the century as the butt of America’s jokes. Taking images from black-face minstrelsy, which was America’s first national popular entertainment form and a mainstay of the American stage until the 1940’s, many of the images of “Blacks” in the first half-century of the comics were not of Blacks at all. Instead they were caricatures derived from the popular stage routines of white males’ gross parodies of “Black life” (originally the slave life of Blacks). Just as minstrels worked “under cork,” the colloquial terminology for their use of burnt cork to blacken their faces for a performance, figuratively these were comics “under cork.”

https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/links/essays/comics.htm

“We Are Literally Slaves”: Black Nanny Dispels The Contented Mammy Myth.

“In folklore, the Black nursemaid was seen as a dutiful, self-sacrificing black woman who loved her white family and its children every bit as much as her own. Yet the popular images of the loyal, contented Black nursemaid, or “mammy,” were unfortunately far from the reality for the African-American women who worked in these homes. In 1912 the Independent printed this quasi-autobiographical account of servant life, as related by an African-American domestic worker, which dispelled the comforting “mammy” myth.”

I am a negro woman, and I was born and reared in the South. I am now past forty years of age and am the mother of three children. My husband died nearly fifteen years ago, after we had been married about five years. For more than thirty years—or since I was ten years old—I have been a servant in one capacity or another in white families in a thriving Southern city, which has at present a population of more than 50,000. In my early years I was at first what might be called a “house-girl,”or, better, a “house-boy.” I used to answer the doorbell, sweep the yard, go on errands and do odd jobs. Later on I became a chambermaid and performed the usual duties of such a servant in a home. Still later I was graduated into a cook, in which position I served at different times for nearly eight years in all. During the last ten years I have been a nurse.

“I have worked for only four different families during all these thirty years. But, belonging to the servant class, which is the majority class among my race at the South, and associating only with servants, I have been able to become intimately acquainted not only with the lives of hundreds of household servants but also with the lives of their employers. I can, therefore, speak with authority on the so-called servant question; and what I say is said out of an experience that covers many years

To begin with, then, I should say that more than two-thirds of the negroes of the town where I live are menial servants of one kind or another, and besides that more than two-thirds of the negro women here, whether married or single, are compelled to work for a living, — as nurses, cooks, washerwomen, chambermaids, seamstresses, hucksters, janitresses, and the like. I will say, also, that the condition of this vast host of poor colored people is just as bad as, if not worse than, it was during the days of slavery. Tho today we are enjoying nominal freedom, we are literally slaves. And, not to generalize, I will give you a sketch of the work I have to do—and I’m only one of many.

I frequently work from fourteen to sixteen hours a day. I am compelled by my contract, which is oral only, to sleep in the house. I am allowed to go home to my own children, the oldest of whom is a girl of 18 years, only once in two weeks, every other Sunday afternoon—even then I’m not permitted to stay all night. I not only have to nurse a little white child, now eleven months old, but I have to act as playmate or “handy-andy,” not to say governess, to three other children in the home, the oldest of whom is only nine years of age. I wash and dress the baby two or three times each day, I give it its meals, mainly from a bottle; I have to put it to bed each night; and, in addition, I have to get up and attend to its every call between midnight and morning. If the baby falls to sleep during the day, as it has been trained to do every day at about eleven o’clock, I am not permitted to rest. It’s “Mammy, do this, ”or“Mammy, do that,” or “Mammy, do the other,” from my mistress, all the time. So it is not strange to see “Mammy” watering the lawn in front with the garden hose, sweeping the sidewalk, mopping the porch and halls, dusting around the house, helping the cook, or darning stockings. Not only so, but I have to put the other three children to bed each night as well as the baby, and I have to wash them and dress them each morning.”

“We Are Literally Slaves”: Black Nanny Dispels The Contented Mammy Myth.