SCOTTSBORO: AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY

The NAACP and the Scottsboro Trial

This 1936 photograph from the collections of the National Portrait Gallery—featuring eight of the nine Scottsboro Boys with NAACP representatives Juanita Jackson Mitchell, Laura Kellum, and Dr. Ernest W. Taggart—was taken inside the prison where the Scottsboro Boys were being held. (NPG, acquired through the generosity of Elizabeth Ann Hylton)

Cartoon by Jacob Burck from The Daily Worker.

“The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), one of the nation’s most prominent civil rights organizations today, was founded in 1909 by leading Black and White Americans concerned with the condition of Blacks in the United States. In particular, the group was formed in response to the lynchings of Blacks in the South.

The organization followed the Scottsboro case in the local southern newspapers but did not have a local representative reporting on the situation; the information they received did not immediately convince the NAACP that the boys were innocent. When Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP, began receiving inquiries on the case, from board member Clarence Darrow, among others, he began a more careful investigation of the incident.

UNITED STATES – APRIL 13: Attorney Samuel Leibowitz addresses a crowd of citizens of Harlem in the Salem M. E. Church, 129th St. and Seventh Ave. Three thousand people packed the church to hear the speeches of Leibowitz and Mrs. Jennie Patterson, mother of one of the accused “Scottsboro Boys.” At the extreme left, on the end of the platform, is William Davis, Harlem Editor., (Photo by NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

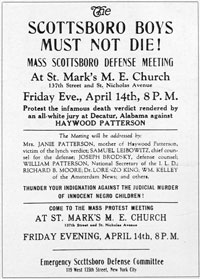

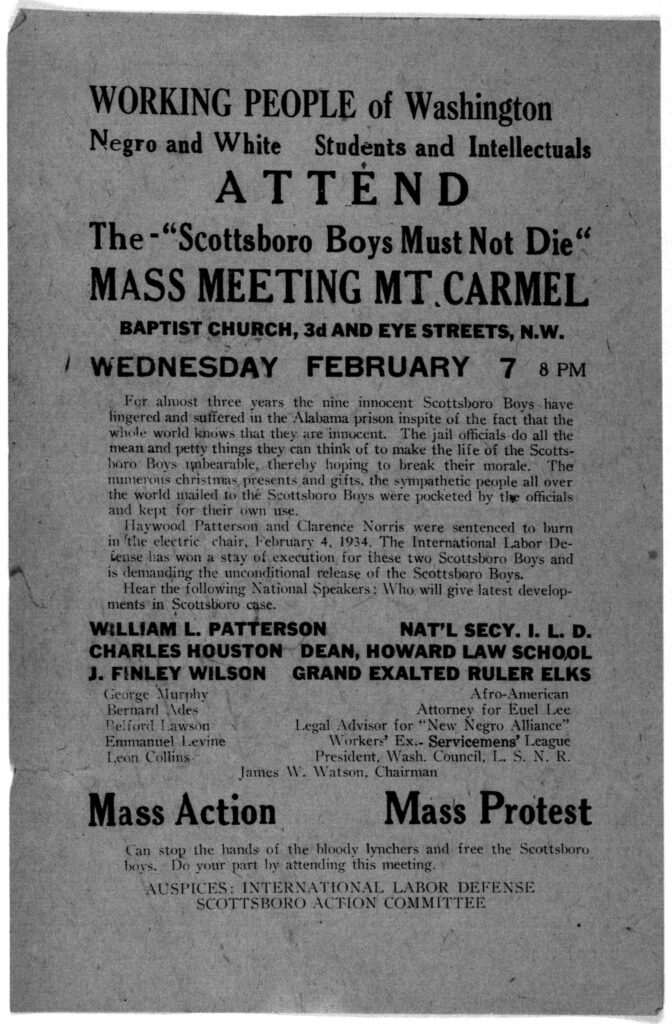

By the time the NAACP made an effort to become involved in the legal defense of the accused, the International Labor Defense had already staked a claim to the case. This led to public relations campaigns by both groups trying to discredit the other. The NAACP thought the I.L.D. was using the Scottsboro case as propaganda for the cause of communism; the I.L.D. thought the NAACP was too moderate, willing to collaborate with the ruling class for small gains. The boys were easily swayed by both organizations but ultimately, the I.L.D. was more successful at courting their parents, and that decided the issue.

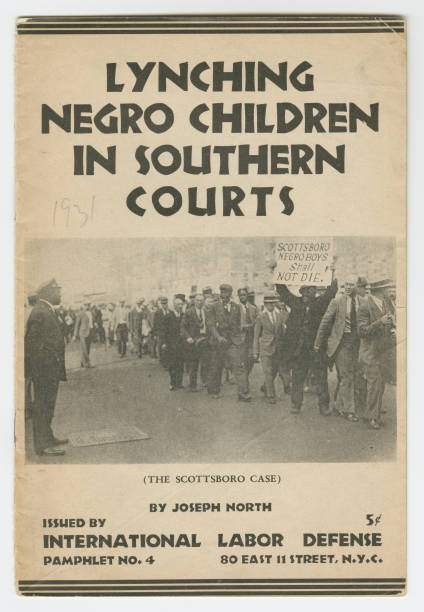

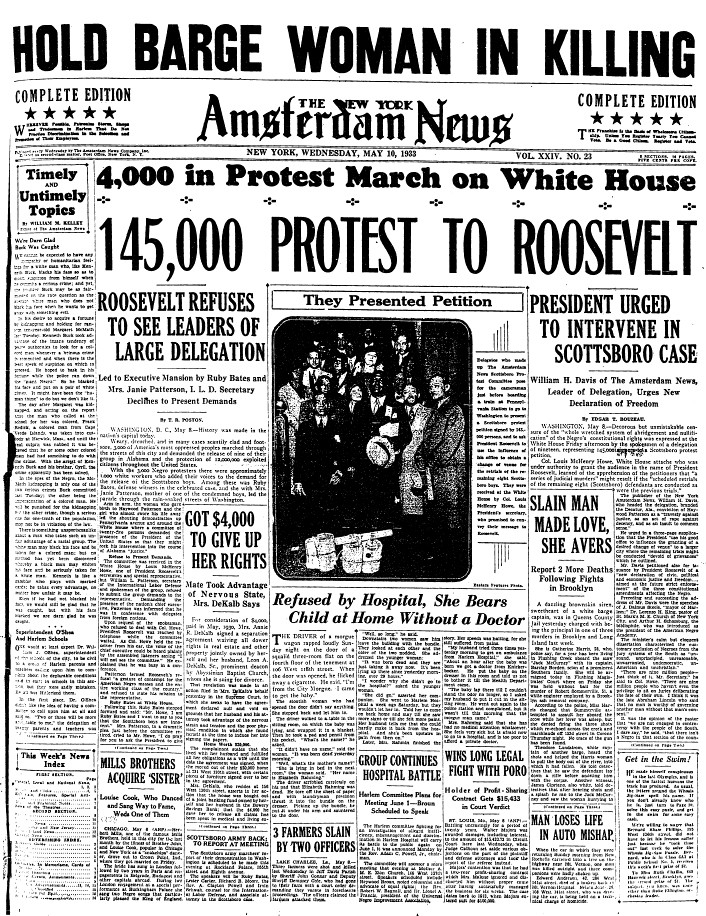

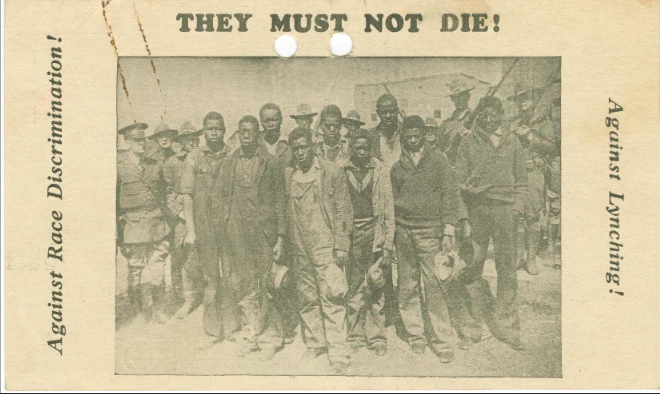

The case of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African-American teenagers, aged 12-19, accused in Alabama of raping two white women in 1931, is commonly cited as an example of a miscarriage of justice in the United States legal system. Pamphlet consisting of black ink on yellowed paper. At the center, a photograph of men marching in support of the Scottsboro boys. Artist Unknown. (Photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images)

Although the I.L.D. officially ran the legal defense, the NAACP never lost interest in the case and watched all the developments carefully. The organization remained active in providing support for the defendants and their families and advancing their cause.

In 1935 the competing groups came together and the Scottsboro Defense Committee was formed. Within the new group, the I.L.D. the position was reduced, and the NAACP was a voting member.

After the compromise outcome of 1937, with four of the young men convicted of rape, Ozie Powell imprisoned for assaulting a deputy, and four of the defendants set free, the NAACP helped find jobs for each of the boys as they left prison.

In the 1970s, when Clarence Norris wanted to put his past behind him, NAACP lawyers helped him receive his pardon from the state of Alabama.” – AMERICA EXPERIENCE – (PBS)

Communist Party of the United States’ members prepare for a march to protest the conviction of Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris, two of the boys in the Scottsboro lynching Trial, Scottsboro, Alabama, December 16, 1933. (Photo by Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images)

Hundreds of demonstrators march in Washington D.C. against the trials in the Scottsboro case. In the Scottsboro case, nine young black men were falsely accused of raping two white women in a freight car.

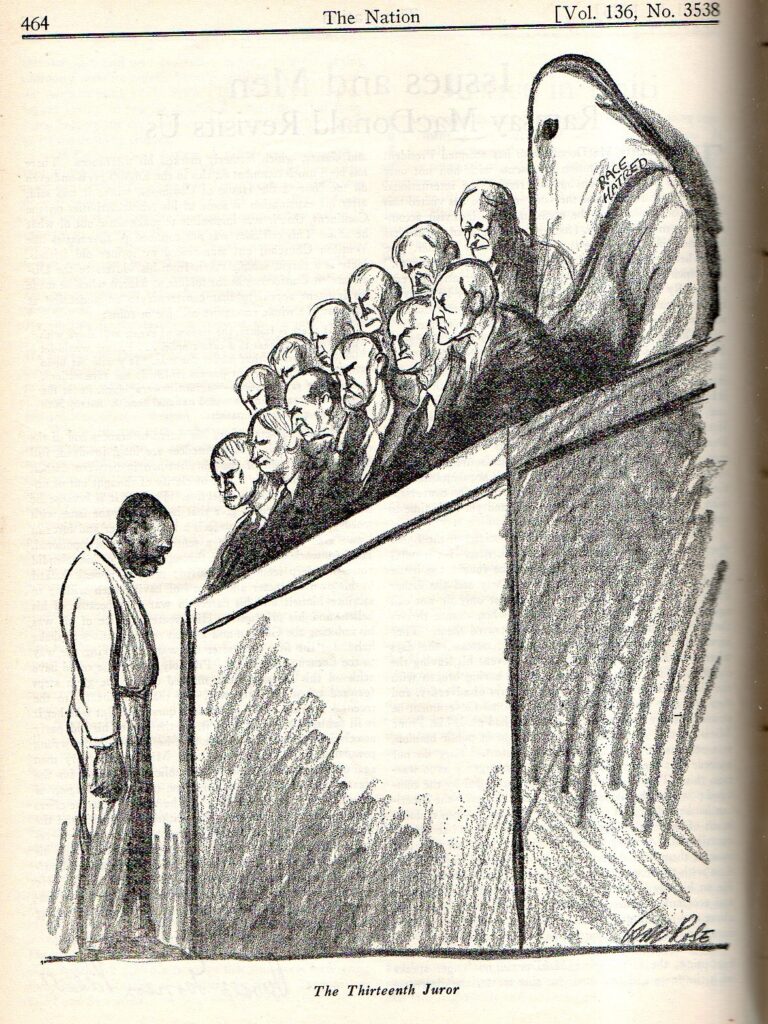

[Image source: “The South Speaks”, by John Henry Hammond, Jr., in The Nation, April 26, 1933, opposite page 465.]

A Timeline of Injustice

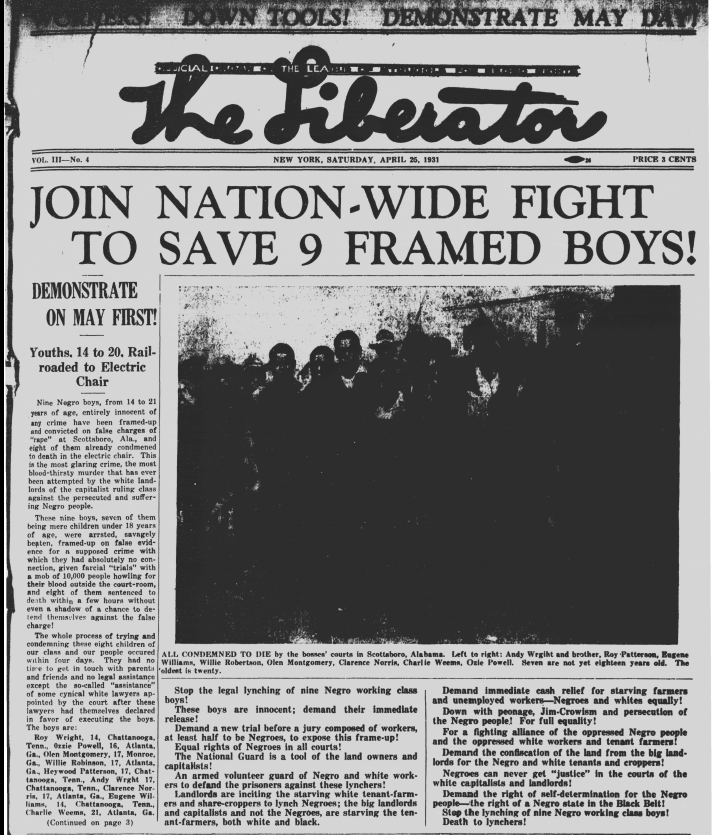

1931: On March 25, a fight breaks out between groups of young Black and White men on a freight car in Alabama. Nine black youths, ages 12 to 19, are arrested, and rape charges are added based on the accusations of two White women. In April, the boys are tried and found guilty — eight are sentenced to die by electric chair, but a mistrial is declared for Roy Wright, the youngest. Throughout the year, progressive organizations call for a rejection of the convictions as “railroading.”

1932: In Patterson v Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court rules the defendants were denied the right to counsel, violating their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. New trials are set.

1933: In January, defense lawyer Samuel Leibowitz takes the case on behalf of the International Labor Defense, the legal arm of the Communist Party in the U.S. At Haywood Patterson’s second trial, one of the women, Ruby Bates, recants the rape charge. Patterson is found guilty anyway. By the end of the year, the trials of Patterson and Clarence Norris end in death sentences for both.

1935: In Norris v Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court rules the exclusion of blacks on jury rolls deprives black defendants of their rights under the law, and the Patterson and Norris convictions are overturned.

Sharon Eberson

‘Scottsboro Boys’ sets the real-life tale of racism and injustice to music

1936: While being transported to the Birmingham Jail, one of the accused, Ozie Powell, attacks a deputy and is shot in the head. He survives but suffers brain damage. In December, Lt. Cov. Thomas Knight meets Leibowitz to negotiate a compromise.

1937: Rape charges against four of the young men — Olen Montgomery, Willie Robertson, Eugene Williams and Roy Wright — are dropped. The four go on to appear in a vaudeville act at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem.

1938: Gov. Bibb Graves meets with the Scottsboro defendants to consider parole, then denies it for the five remaining men.

1943: Charles Weems, the oldest of the boys when they were arrested, is released on parole.

1946: Ozie Powell and Clarence Norris are released on parole. Haywood Patterson escapes from prison.

1950: Andy Wright is paroled and Haywood Patterson’s autobiography, “Scottsboro Boy,” is released. In December, Patterson gets into a bar fight in which a man dies. He is sentenced to 6-15 years in prison.

1952: Haywood Patterson dies of cancer at age 39.

1976: Alabama Gov. George Wallace officially declares that Clarence Norris, the last of the nine Scottsboro defendants, is not guilty.

1979: Clarence Norris’ “The Last of the Scottsboro Boys” is published. He dies in 1989.

2004: The town of Scottsboro dedicates a historical marker at the Jackson County Courthouse in commemoration of the boys’ struggle for justice.

2010: The Scottsboro Boys Museum opens in Scottsboro, Ala. In New York, the off-Broadway musical “The Scottsboro Boys,” created in the framework of a minstrel show, moved to Broadway for only two months. It received 12 Tony Award nominations, second only to “The Book of Mormon,” but won none. It later became a hit in London.

2013: Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley officially exonerates the last of the Scottsboro Boys.

— Sharon Eberson, Post-Gazette

First Published September 6, 2017

The Scottsboro Boys in Their Own Words

Selected Letters, 1931–1950.

This is a collection of letters written by the nine African American defendants in the infamous March 1931 Scottsboro, Alabama, rape case. Though most of the defendants were barely literate and all were teenagers when incarcerated, over the course of almost two decades in prison they learned the rudiments of effective letter writing and in doing so forcefully expressed a wide range of perspectives on the falsity of the charges against them as their incarceration became a cause célèbre both in the United States and internationally.

Central to this book is the chronologically structured presentation of letters (1931–1950), including some correspondence from attorneys and members of Scottsboro support committees. The original grammar, syntax, and vernacular of the defendants are maintained in a desire to preserve the authenticity of these letters.