THE BLINDING OF ISAAC WOODARD | ARTICLE

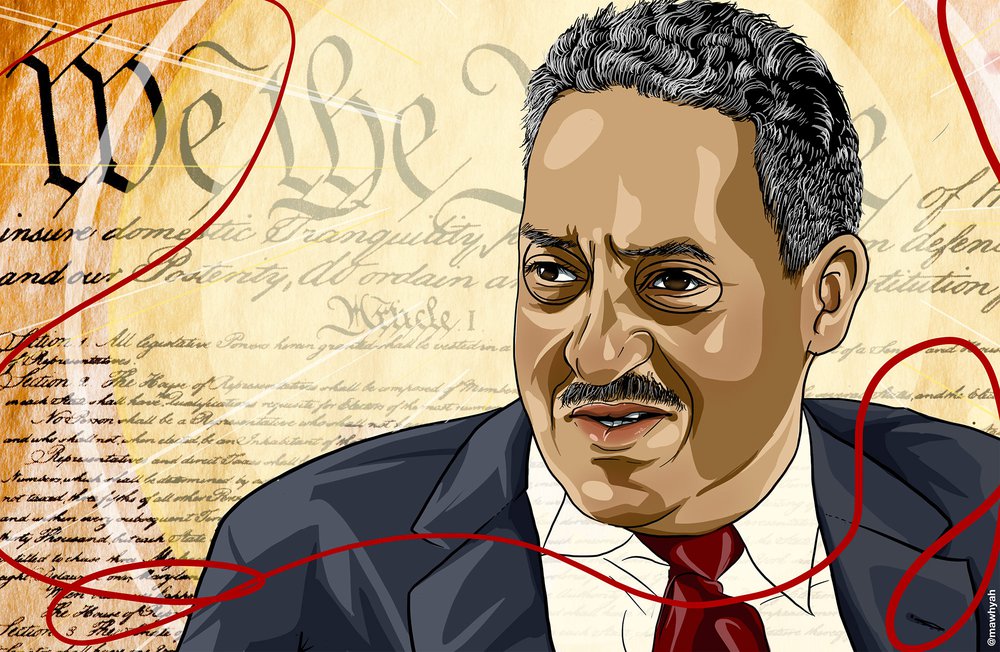

Mr. Civil Rights

Before Brown v. Board of Education, there was Briggs v. Elliot—the case that launched Thurgood Marshall’s fight to end segregation in America’s schools.

Mr. Civil Rights

“In May 1950, lawyer Thurgood Marshall faced a question that confronts so many activists in pursuit of a goal: Should he continue to play the long game, pressing for incremental social change, or had the time come to attempt a big leap forward, despite the risks?

For Marshall, the goal was equal opportunity for Black students in America’s schools. How to arrive at that end was the question that, as head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Legal Defense and Education Fund, he needed to answer.

In the 1930s, Marshall’s legal mentor and NAACP colleague Charles Hamilton Houston had warned the association against overreach, saying, “Don’t shout too soon.” Under Houston’s steady leadership, the NAACP enacted a careful case-by-case, year-over-year strategy to undermine the doctrine of separate but equal established by the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision.

Once Houston was gone, NAACP leaders pushed for a more aggressive approach, and Marshall had to decide how to proceed.”

Art by Mawhyah Milton. Source photo: Library of Congress

In May 1950, lawyer Thurgood Marshall faced a question that confronts so many activists in pursuit of a goal: Should they continue to play the long game, pressing for incremental social change, or has the time come to attempt a big leap forward, despite the risks? For Marshall, the goal was equal opportunity for Black students in America’s schools. How to arrive at that end was the question that, as head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Legal Defense and Education Fund, he needed to answer.

In the 1930s, Marshall’s legal mentor and NAACP colleague Charles Hamilton Houston had warned the association against overreach, saying, “Don’t shout too soon.” Under Houston’s steady leadership, the NAACP enacted a careful case-by-case, year-over-year strategy to undermine the doctrine of separate but equal established by the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Under this gradualist approach, the NAACP pursued litigation that could clearly demonstrate that separate educational resources for Black students were unequal to those of whites. Houston’s blueprint had pushed at Plessy’s edges rather than trying to overturn it, however. Association attorneys argued for equal resources rather than attempt to abolish segregation outright.

Now Houston was gone, felled by a heart attack a month earlier, in April. Other NAACP leaders felt a more aggressive approach was required, and Marshall had to decide how to proceed.

At the height of summer, he convened a meeting at the association’s headquarters in New York City. Fifty-seven members—43 attorneys from the Legal Defense Fund and National Legal Committee and 14 branch and regional leaders—resolved “to end segregation once and for all.” They inaugurated a new era of NAACP litigation. There would be no more nudging against Plessy and other segregationist statutes; the time had come to try to topple them completely. It was an exceedingly ambitious goal given the state of American race relations at the halfway mark of the century. And Marshall still needed a strategy for achieving it.

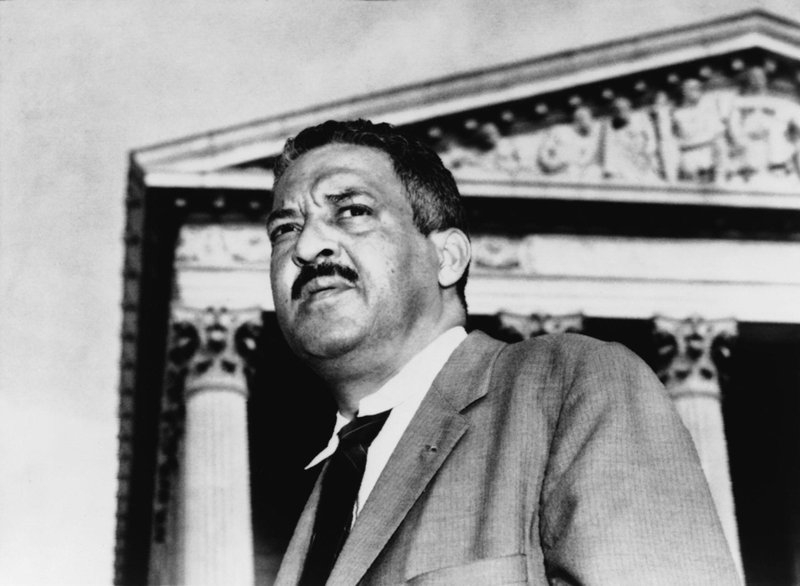

Thurgood Marshall gives a press conference in his role as chief counsel for the NAACP, 1955. Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock Photo

In the country’s history, no one had ever filed a case directly challenging public school segregation. At 42, Marshall was a pragmatist with hard-won knowledge of America’s judicial system. He was on the lookout for a case outside of the deep South, where NAACP lawyers had better chances for success with more open-minded judges and juries. But in the meantime, there was Clarendon County, South Carolina.

The disparities between white and Black children’s resources in Clarendon County’s School District Number 22 were indisputable. The district served a rural community that was three-fourths African American. But where the county’s white schools were brick-and-mortar structures with maintained grounds and modern facilities, Black students took classes in dilapidated wooden shacks with no indoor plumbing, forcing them to get water from a community well and use outhouses no matter the elements. Without buses, the Black children walked up to nine miles to get to school.

The one-room Oak Grove schoolhouse in Clarendon County shared its grounds with a church and a graveyard first used as a burial ground for enslaved persons, 1950. South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

To Marshall, Clarendon County was a perfect opportunity to litigate equal facilities, transportation, and other resources for the county’s Black children. But it would be foolhardy to push for full desegregation. Marshall knew how slim the odds were of victory in South Carolina. He also understood how dangerous bringing a legal challenge there would be for the case’s plaintiffs, who would bear the full brunt of white supremacist retaliation for even daring to suggest integration.

Marshall’s hand was forced, however, by the presiding judge, J. Waties Waring. Waring, a white Charlestonian, was the rarest of birds: a Southern activist jurist who supported civil rights. The two first met in 1944 when Marshall argued Duvall v. Seignous, a case about disparities in teacher salaries, before the judge’s bench. Waring, past retirement age by 1950 and a pariah to much of white South Carolina for his racial views, was ready to make one last judicial strike against America’s apartheid educational system.

Marshall arrived in Clarendon County to argue Briggs v. Elliott in November 1950. The suit had come to be named after its lead plaintiffs, navy veteran Harry Briggs and his wife, Eliza Briggs, who was a maid at a local motel. But Waring challenged Marshall to refile the case as a direct attack on the constitutionality of segregation. The new suit could claim that separate educational opportunities, even if materially equal, were a denial of the Briggs’ plaintiffs’ 14th Amendment rights. Neither man was under any illusions that the case would succeed; losing seemed inevitable. But, Waring argued, by bringing this challenge in federal court, a loss guaranteed the case would hopscotch over the U.S. Court of Appeals and be placed directly on the Supreme Court’s docket.

The stakes were immense. If the NAACP were to lose this appeal before the highest court in the land, Plessy v. Ferguson would be reaffirmed and decades of dogged, meticulous work would be lost. It might be decades more before there would be another opportunity to challenge segregation head-on. Marshall was conflicted but decided to move forward with Waring’s plan. Briggs v. Elliott would now be heard before a three-judge panel including Waring.

On May 28, 1951, Black South Carolinians rose before dawn to travel to the federal courthouse in Charleston, despite the risk of reprisals that could come from merely having appeared there. Joining the hundreds of journiers were reporters who wanted front-row seats to history. The NAACP’s team was performing for a packed courtroom, but also on a national stage as reporters bore witness for The New York Times, New York Post, the Associated Press, and numerous other national and local publications.

At the very outset of the hearing, the school district’s lawyer attempted to upend the trial with a surprise announcement: Clarendon County fully acknowledged that Black and white students’ educational experiences were unequal. To rectify the situation, South Carolina planned to issue $75 million in state bonds to bring Black schools up to par. There was, therefore, no need, the district’s lawyer reasoned, even to hear the case. Blindsided at first, Marshall recovered, arguing that the County’s “statement just made has no bearing on this litigation,” since the NAACP’s suit maintained “segregation in and of itself is unlawful.” The case proceeded, and Marshall’s team sought to demonstrate the injury inflicted upon Black children by segregated education.

Marshall lost Briggs v. Elliott as expected. Two of the three judges who heard the case agreed that Clarendon County’s Black students received an inferior education and called for the inequities to be corrected. But they held that the decision to segregate schools remained with the state. As Judge Waring had foreseen, however, the loss ensured a Supreme Court appeal. Ultimately, that appeal was consolidated with four other cases that, three years later, led to the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision mandating the desegregation of America’s public schools.

Thurgood Marshall, NAACP Chief Counsel, is shown in front of the Supreme Court, 1958. Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock Photo

Back outside the Charleston Federal Courthouse on that late May day in 1951, Marshall marveled at the crowd of African Americans surrounding the building and extending down the block. Many of the attendees had made the trip from hours away to witness the unprecedented case. They had also come simply to see and hear Marshall himself, the man they called Mr. Civil Rights for his seemingly fearless crusade for racial justice.

Entering the courthouse, Marshall remarked to his NAACP deputy Robert Carter, “Bob, it’s all over.” Carter asked Marshall what he meant.

As the man who would become the Supreme Court’s first Black justice looked around, he couldn’t know the role that yet awaited him. Nor could he know that, as late as 2016—62 years after the Brown v. Board decision and 23 years after his death—the United States Justice Department would still be monitoring and enforcing nearly 200 open federal school desegregation court cases.

Turning to his deputy, Marshall said, “They’re not scared anymore.”

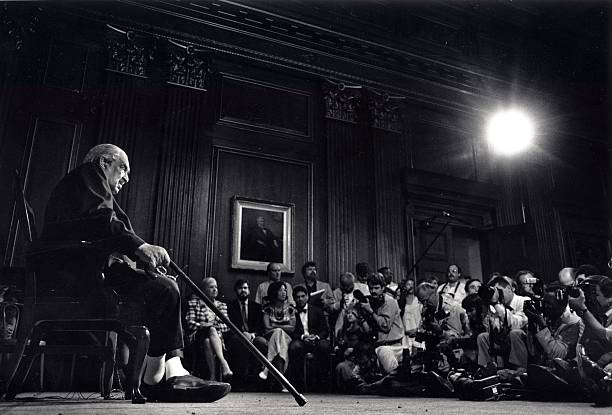

WASHINGTON, DC – FEBRUARY 13: The first Black American, Thurgood Marshall, appointed to the Supreme Court retires at age 82, in Washington, DC on June 27, 1991. (Photo by John McDonnell/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

- Thurgood Marshall

- BIRTH DATE

- July 2, 1908

- DEATH DATE

- January 24, 1993

- In 1967, Thurgood Marshall became the first African American justice of the Supreme Court.

- EDUCATION

- Howard University School of Law, Lincoln University, Colored High and Training School (Frederick Douglass High School)

- PLACE OF BIRTH

- Baltimore, Maryland

- PLACE OF DEATH

- Bethesda, Maryland

Marshall’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 5, Grave 40-3).

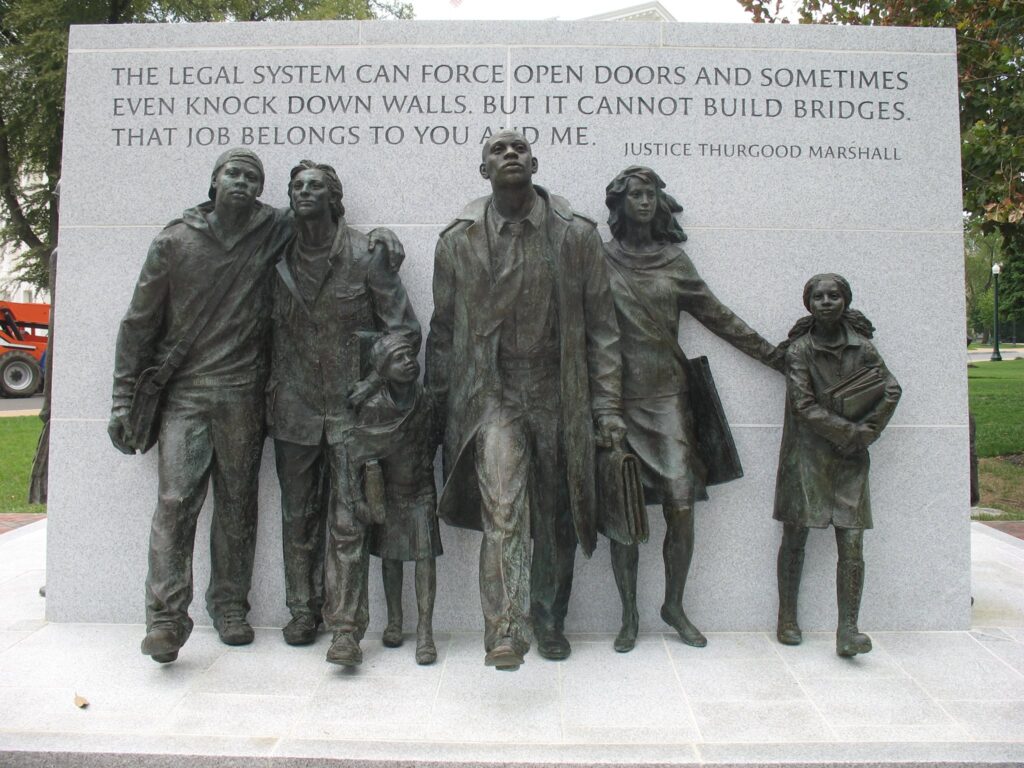

Memorials

U.S. Senator Ben Cardin (left) and Maryland Attorney General Doug Gansler talk in Lawyers Mall, near a statue of Thurgood Marshall. (October 2007).

Numerous memorials have been dedicated to Marshall. An 8-foot (2.4 m) statue stands in Lawyers Mall adjacent to the Maryland State House. The statue, dedicated on October 22, 1996, depicts Marshall as a young lawyer and is placed just a few feet (a meter or two) away from where stood the Old Maryland Supreme Court Building, the court where Marshall argued discrimination cases leading up to the Brown decision.[41] The primary office building for the federal court system, located on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., is named in honor of Marshall and contains a statue of him in the atrium.[citation needed]

In 1976, Texas Southern University renamed its law school after the sitting justice.[42]

In 1980, the University of Maryland School of Law opened a new library, which it named the Thurgood Marshall Law Library.[43]

In 2000, the historic Twelfth Street YMCA Building located in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C., was renamed the Thurgood Marshall Center.[citation needed]

The major airport serving Baltimore and the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C., was renamed the Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport on October 1, 2005.[citation needed]

The 2009 General Convention of the Episcopal Church added Marshall to the church’s liturgical calendar of “Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints”, designating May 17 as his feast day.[44]

His membership of the Lincoln University fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha was to have been memorialized by a sculpture by Alvin Pettit in 2013.[45]

The University of California, San Diego renamed its Third College after Marshall in 1993.[46]

Marshall Middle School, in Olympia, Washington, is also named after Marshall, as is Thurgood Marshall Academy in Washington, D.C.

@ALL RIGHTS RESERVED (2021) – Iforcolor.org/Dale Shields