Page 2 – 12

A Magical Journey

Looking back at the journey of the little girl, …young lady

…legendary artist*

“Don’t Throw Me Into the Briar Patch” – Joel Chandler Harris

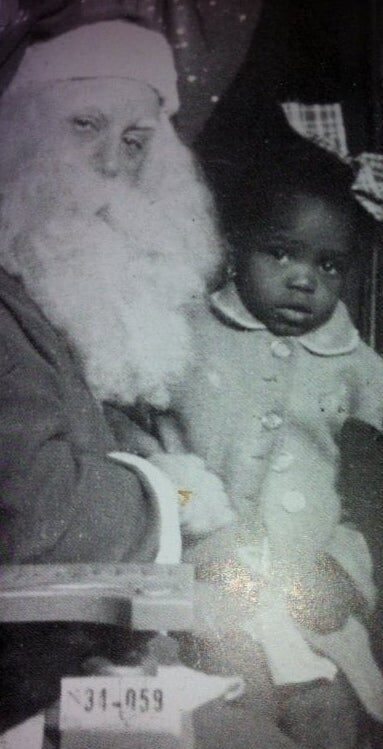

Adelle Gautier with Santa. (1950)

Prior to the Civil Rights Act*, Black children could not visit Santa Claus at most big Canal Street** department stores. After the legislation was passed, stores made it a point to welcome every child.

*[ The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first federal civil rights legislation passed by the United States Congress since the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The bill was passed by the 85th United States Congress and signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on September 9, 1957. It established the Civil Rights Division in the Justice Department and empowered federal officials to prosecute individuals that conspired to deny or abridge another citizen’s right to vote. – The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, is considered one of the crowning legislative achievements of the civil rights movement. First proposed by President John F. Kennedy. ]

**[ Canal Street is a major thoroughfare in the city of New Orleans. Forming the upriver boundary of the city’s oldest neighborhood, the French Quarter or Vieux Carré, it served historically as the dividing line between the colonial-era city and the newer American Sector, today’s Central Business District. ]

The Lafitte Projects

Adelle Gautier was born in New Orleans, Louisiana,

and grew up in the Lafitte housing development.

“The Lafitte Projects were one of the Housing Projects of New Orleans and were located in the 6th Ward of New Orleans Treme neighborhood. It was one of Downtown New Orleans’ oldest housing developments and was severely flooded and damaged during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. It was one of the first housing projects for African Americans in Louisiana. During its early years, it was labeled as the largest and finest U.S. Housing Authority low-rent project in the South. Lafitte was the fifth of six local housing projects to be built in New Orleans.” – Wikipedia.org

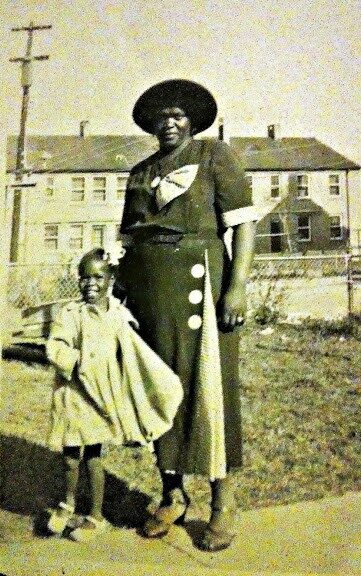

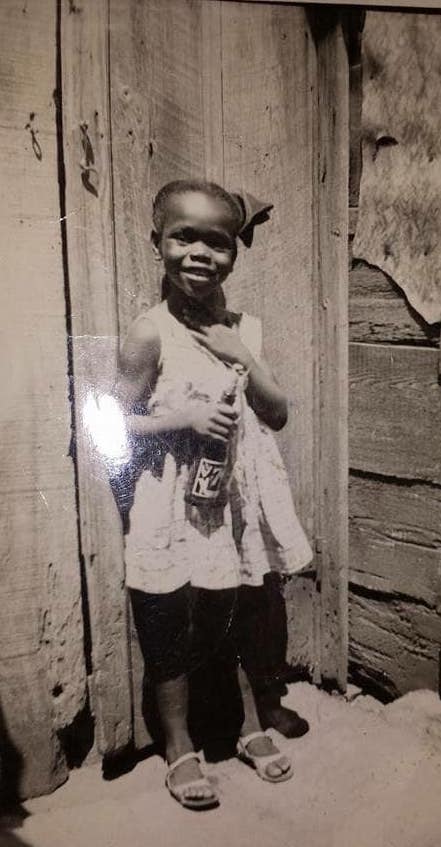

“Most little ‘Negro’ girls had this photoshoot experience in the “40s and ’50s“

Tessie and her bottle doll are in the yard visiting at 2309 St. Ann St. in New Orleans. ca,1952

Carnival time! Tremé. (Lafitte)

[ The holiday of Mardi Gras is celebrated in all of Louisiana, including the city of New Orleans. Celebrations are concentrated for about two weeks before and through Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday. Usually, there is one major parade each day; many days have several large parades. Wikipedia – Mardi Gras, or Fat Tuesday, refers to events of the Carnival celebration, beginning on or after the Christian feasts of the Epiphany (Three Kings Day) and culminating on the day before Ash Wednesday, which is known as Shrove Tuesday. ]

“Confirmation at St. Peter Claver Parish. The smell of incense made me sick and I didn’t appreciate the ceremonial slap given by Archbishop Rummel.“

At McDonogh 35 High School and Dillard University,

she studied English and discovered her love of theater.

“I had graduated from high school and had been accepted at the university that I went to and my grandmother called the house and asked, not asked, but told my mother to send me over because the grandchildren of these people that she worked for were in town and they needed someone to babysit while the mother went shopping on Canal Street. She said they would pay me $20 to do it.”

And I was thinking, well I guess $20 is more than the $5 a day and carfare that she was being paid. I remember saying “I’m on my way to college. I’m not taking care of any White kids, babysitting, and anything like that. I don’t want to be anybody’s maid or nursemaid.” I remember that incident. I remember being insulted and just hurt and outraged, but I don’t remember if I went or not. I don’t know, it’s a thing that’s kinda blocked. That’s why, I guess, I’m doing this piece. I think in the course of doing this piece I’ll figure out if I went or not. But I honest to God don’t remember whether or not I went. My grandmother’s dead. My mother’s dead. My sister who also worked for that family – she’s dead. So, everybody, I could ask if I went or not … unless I find those people and ask them, which is another whole thing because they probably don’t remember … it probably was nothing to them. It is a different reason for my not remembering.” – Adelle

“I lead such a charmed life. Sometimes I feel like my life is a Forrest Gump movie.”

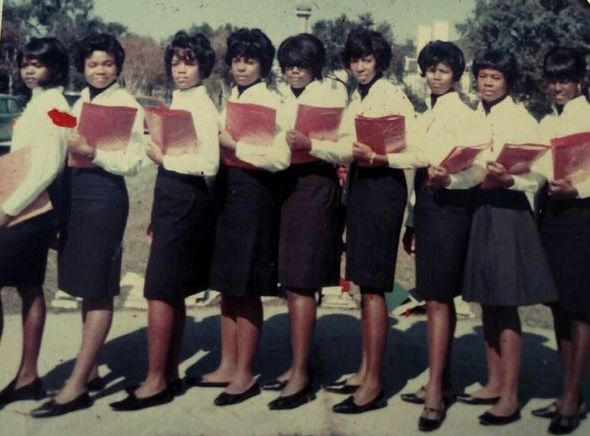

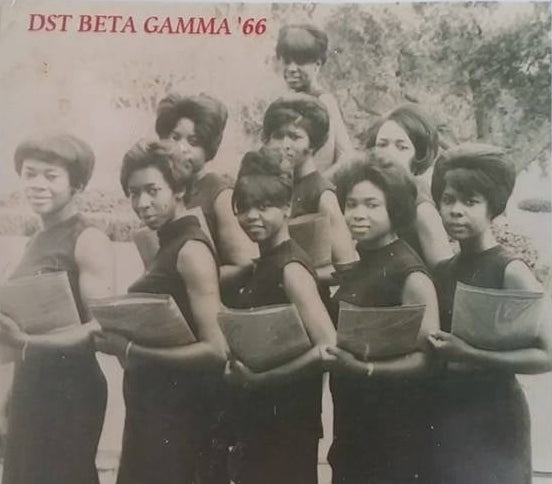

Delta Sigma Theta

Fall 1965, Beta Gamma Chapter III Delta Sigma Theta.

First in line, “DiddyBop “ [Dillard University] – Jamila D. Hunter, JA Alston, Ruby Jackson, Jennifer Jones-Riggins DeBose, Pearl Leonard-Rock, Vanessa Cross, Dodo-Seriki, Candice Carnage, Michelle Rogers, Tracey Ellis Leon, Taaqua Lacy-Williams, Doctah Tiffany Camille R. Quinn, Camille Williams, Aye Dee, Cyronne Washington Counts, Aeja Washington

Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. (ΔΣΘ) is a historically African American sorority. The organization was founded by college-educated women dedicated to public service with an emphasis on programs that assist the African American community. Delta Sigma Theta was founded on January 13, 1913, by twenty-two women at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Membership is open to any woman who meets the requirements, regardless of religion, race, or nationality. Women may join through undergraduate chapters at a college or university, or through an alumnae chapter after earning a college degree. – Wikipedia.org

One of the largest sororities founded in the U.S., more than 350,000 initiated members are college-educated women.

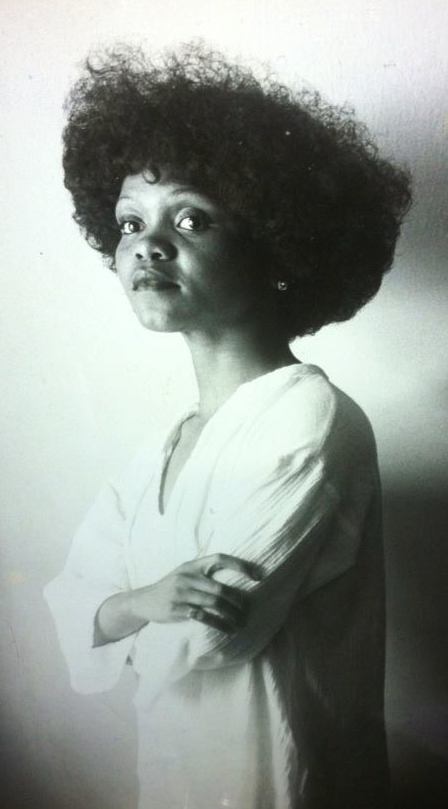

TRAINING

After college, Gautier headed off to Boston, ostensibly to study law, but instead pursued her nascent acting career with the City Stage Company. She returned to New Orleans in the 1970s, where she took a job as a city planner during the Moon Landrieu administration and immersed herself in the burgeoning Black Arts (Theater) Movement.

“The Black Arts Movement was the name given to a group of politically motivated Black poets, artists, dramatists, musicians, and writers who emerged in the wake of the Black Power Movement. The poet Imamu Amiri Baraka is widely considered to be the father of the Black Arts Movement, which began in 1965 and ended in 1975.

After the assassination of Malcolm X on February 21, 1965, those who embraced the Black Power movement fell into one of two camps: the Revolutionary Nationalists, who were best represented by the Black Panther Party, and the Cultural Nationalists. The Cultural group called for the creation of poetry, music, novels, visual arts, and theater to reflect pride in Black history and community. This new emphasis was an affirmation of the autonomy of Black artists to create Black art for Black people as a means to awaken a Black consciousness and achieve political and social liberation.”

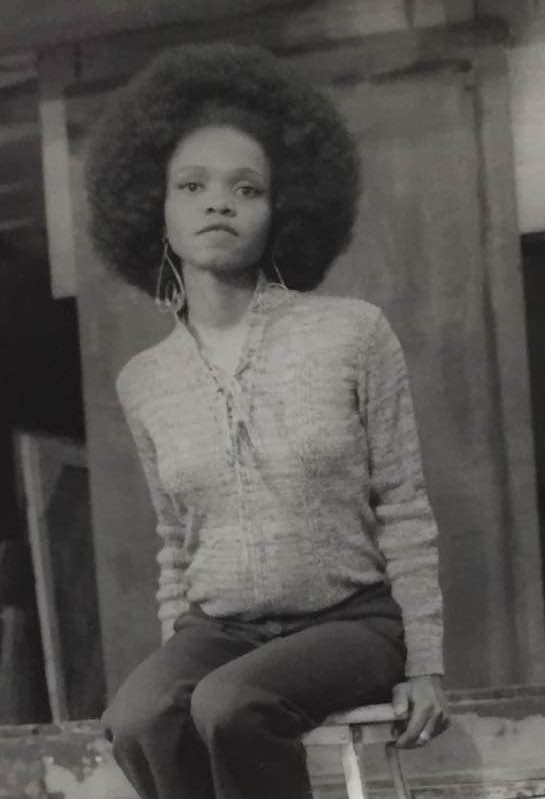

Adelle at 29 years.

Photo by Owen Murphy

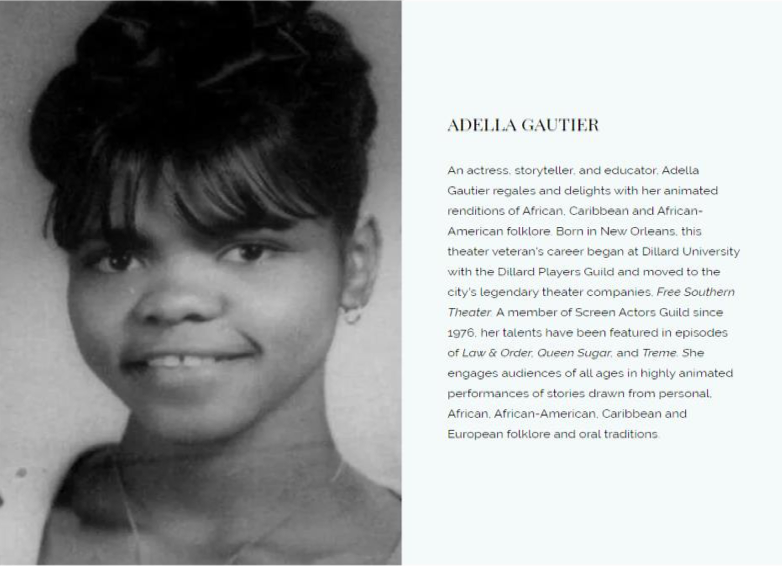

Gautier has a B.A. in English from Dillard University, New Orleans, Louisiana, and studied Film and Communications at the University of New Orleans. Her career began at Dillard University with the Dillard Players Guild and moved to New Orleans’s legendary theater companies, Free Southern Theater and Dashiki Project Theater.

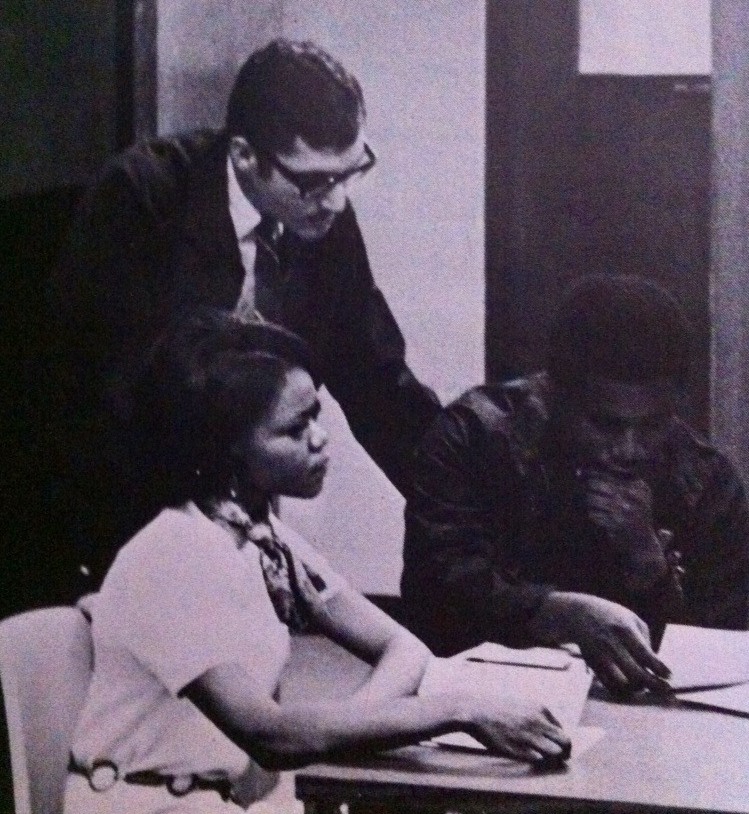

Paul Valteau , Adella Gautier, Richard Stewart , Dillard University 1969.

DILLARD UNIVERSITY

Pioneering in Theatre Arts

“Throughout its existence, Dillard has worked to fulfill the long-standing need for cultural institutions rooted in the community that reflect the aspirations and concerns of African Americans. Black theatre, in particular, has offered a means of speaking about and challenging racism in the face of segregation and oppression.9 Representing African Americans as universal characters, many theater companies that arose in the 1960s with the Black Arts movement began to break new ground in the portrayal of African Americans through characters that mirrored their lives. Performers portrayed dignified characters with a full range of emotions rather than stereotypes of African Americans often performed by White entertainers. With the uncertainties of Black and White relations, plays and theater production were the “vital genealogy of African American performance.”10 Throughout the Black Arts movement, African American artists squarely addressed racial issues, while continuing to shape American culture through their creative work.”

Makenzee Brown

University of New Orleans

BLACK THEATRE MOVEMENT

The Black Arts Movement started in 1965 when poet Amiri Baraka [LeRoi Jones] established the Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem, New York, as a place for artistic expression. Artists associated with this movement include Audre Lorde, Ntozake Shange, James Baldwin, Gil Scott-Heron, and Thelonious Monk.

The Black Theatre Movement was closely allied with the civil rights movement — “John O’Neal and Doris Derby were also directors of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). They presented plays by Langston Hughes, John O. Killens, James Baldwin, and Ossie Davis as well as providing a space for their members to write their own plays. The founders sought to introduce free theater to the South, both as a voice for social protest, and to emphasize positive aspects of African-American culture” – Wikipedia.org

Junebug Productions

Junebug Productions is the organizational successor to the Free Southern Theater (FST)with a mission to create and support artistic works that question and confront inequitable conditions that have historically impacted the Black community. Through interrogation, we challenge ourselves and those aligned with the organization to make greater and deeper contributions toward a just society.

In 1963, Field Secretaries John O’Neal and Doris Derby along with student leader Gilbert Moses co-founded FST to be a cultural wing of SNCC. FST went on to become a major influence in the Black Arts Movement. In 1965 FST moved its base from Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi to New Orleans. The theater’s first professional tour was of Freedom School Project sites. It continued to use arts to support the Civil Rights Movement through a community engagement program and training opportunities for local people interested in writing, performing, and producing theater as well as touring.

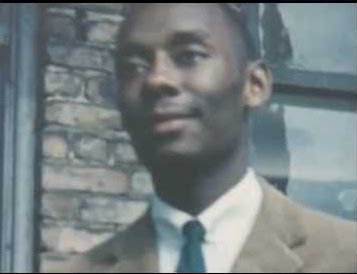

John O’Neal

John O’Neal, the co-founder of the Free Southern Theater (FST)–one of the cultural arms of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)–has died at the age of 78. Less well known than the other SNCC institutions, such as the Freedom Singers and the Freedom Schools, the FST played a central part in the 1964 Freedom Summer organizing campaign. From this experience, O’Neal spent a lifetime building cultural institutions, experimenting with the use of theater in the service of social change, and leading the way in fusing art and activism.

As O’Neal began his work in arts and the civil rights movement he realized “there was little coherency in the way people think about art. It was just incoherent.” Making money “was the only consistency I could see,” he reflected. O’Neal sought another way:

“There are those who view art as…all about individuals…the prerogative to express their feelings and views…There are others who see art as part of the process of the individual in the context of community and the community coming to consciousness of itself. In the first case, the artist is seen as a symbol of the antagonistic relationship between the individual and society. In the second case, the artist symbolizes the individual within the context of a dynamic relationship with a community…Obviously, the latter view is the one that I identify with…That gives basis to the notion that the artist is a vehicle for a force greater than him—or herself…it includes the whole spiritual life that we participate in, as well as the whole political, social and economic life.”

This was the guiding principle for John O’Neal’s life. As he told his father as he embarked on founding the FST, “I don’t intend to work for a living. I intend to live for my work.” He noted, “I’ve been struggling to find the way art contributes to the way people live and solve problems ever since.”

During his time as a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, John O’Neal worked with Doris Derby on an adult literacy program in Mississippi. O’Neal recalled a fateful night in October 1963 when the idea for the Free Southern Theater was born.

The Dashiki Project Theatre

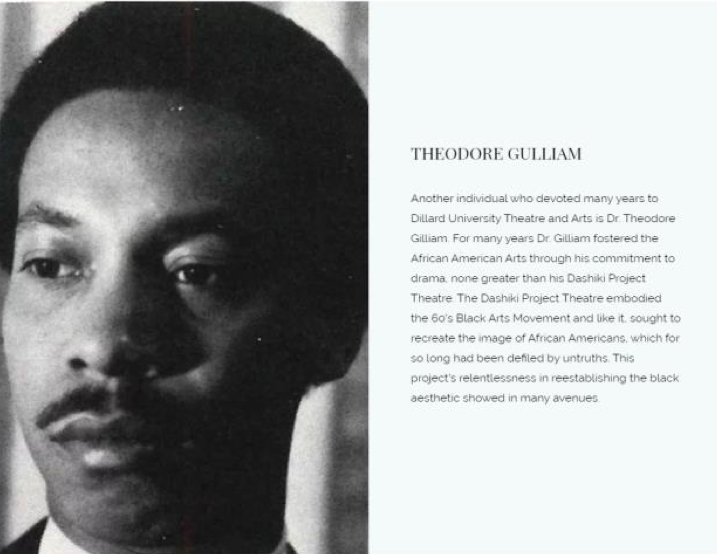

“The Dashiki Project Theatre was founded in 1968 and was initially funded by a grant from the Office of Economic Opportunity. The primary goal of the theatre was to present “an accurate portrayal of the Black experience for the Black community.” The Artistic Director for the company was Dr. Ted Gilliam, who is also the Director of the Drama department at Dillard University. The majority of the Actors and Actresses came from Dillard University’s Players’ Guild.” – Wikipedia.org

(Dr.) Theodore Gilliam: Fostering Modern Black Arts and Cultural Expression

“Another individual who devoted many years to Dillard University Theatre is Dr. Theodore Gilliam. Dr. Gilliam fostered the African American Arts through his commitment to drama, none greater than his Dashiki Project Theatre. The Dashiki Project Theatre embodied the 1960s Black Arts Movement and like it, sought to redefine the place of African Americans within American culture and politics. This project was relentless in its efforts to the Black aesthetic, in the era of Black Power when students, in particular, were becoming more militant in their confrontation with a racist political system and more fervent in their commitment to racial solidarity.

Dillard University Theatre was a major contributor to two unique festivals held at the university: The Afro-American Arts Festival and The Black World Expression Festival. These festivals were held over a three-year span, with the first festival opening in the spring of 1969 and the last festival ending in 1971.

The famed Afro-American Arts Festival was dedicated to celebrating the various forms of African Art. Above all, The Dillard University Theatre presented a safe and welcoming environment for African Americans to experience many forms of art, that would otherwise be unavailable. The Black World Expression Festival was dedicated to understanding the “Black Experience” in Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States, and provided yet another successful Afro-Centric celebration through the support of the Dillard University Players and supporting administrators.28 These festivals came during a time when Black arts creativity flowed, and while African Americans throughout the city came together to bring peace within the Black arts community.”

Makenzee Brown

University of New Orleans

Marie Slade, Harold Evans, Danielle Edinburgh-Wilson, Carol Dickerson Sutton, Gwendolyne Foxworth, Adella Gautier, Donald Matthews, Norbert Davidson, and Patricia Hill

The Amistad Research Center and Dashiki Project Theatre are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Dashiki Project Theatre, one of the country’s prominent community theaters.

“Dashiki Project Theatre demonstrated a rare commitment to excellence and freedom in the arts of the South. Dashiki Project Theatre compellingly spoke to the needs of the Black community, at a time when Black identity was in crisis. By the year 1975, Dashiki Project Theatre was known in New Orleans as “New Orleans Most Productive Theatre” (Dashiki Project Theatre Fifteenth Anniversary1968-83).” – Stanley R. Coleman

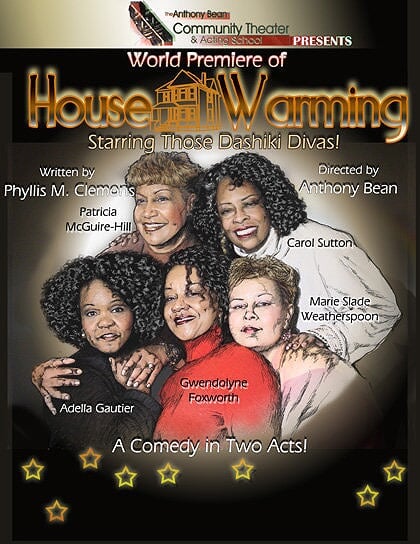

At Dashiki she honed her acting skills and became one of what former Times-Picayune theater critic David Cuthbert dubbed the Dashiki Divas.

“Women were also central to the company as performers and directors. The plays that Dashiki Project Theatre selected gave great opportunities to women to perform and garner praise from the media. From Dashiki’s inception, theatre critics in the New Orleans area were fascinated by the performances of the women. Numerous critical and positive reviews give evidence of the power of these actresses.”

Pat McGuire Hill, Gwendolyne Foxworth, Adelle Gautier, Barbara Tasker, and Carol Sutton

“Critics like David Cuthbert acclaimed the performances of such Dashiki notables as Carol Sutton, Patricia McGuire, Claudia Miller, Adella Gautier, Barbara Tasker, Thelma Hinson, and Andre Cazenave.” – Stanley R Coleman

THREE DASHIKI DIVAS. Carol Sutton, Pat Hill, and Adella Gautier. (referring to Dashiki Project Theater for those of you who may not remember).

Additionally, she has trained in creative drama workshops with Dorothy Heathcote. Barbara Salisbury and acting with Ernie McClintock, Steve Kent, and the Dah Theater.

Ernie McClintock (1937–2003), the founder of Harlem’s Afro-American Studio for Acting and Speech, the 127th Street Repertory Ensemble, and the Jazz Actors Theatre in Richmond preached the “Theatre of Common Sense,” later known as “Jazz Acting.” This unsung hero of the American theatre challenged actors to integrate their observations of daily life in Black communities with their training in music, history, voice, and movement to be equipped to play anything from Baraka to Shakespeare. Over McClintock’s 40-year career, he shaped the work of hundreds of performers who continue to carry his message of self-determination and community.