Page 10 – 20

The Trial

A travesty of Justice – A hallmark of White Supremacy

“Because they had already been acquitted, they could not be tried again. Neither ever served time for Till’s death.”

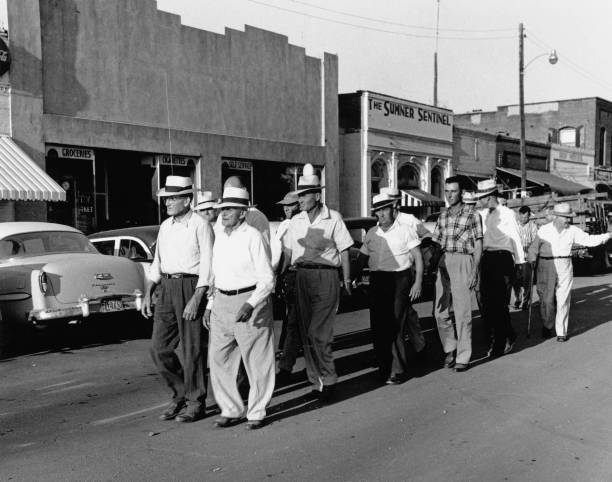

The jury in the Emmett Till trial outside Sumner courthouse during the trial of those accused of Till’s murder, in Sumner, Mississippi, 23rd September 1955. Black teenager Emmett Till was kidnapped and murdered after he was alleged to have whistled at a White woman, Carolyn Bryant. American farmer Gus Ramsey, American farmer James Toole, American insurance seller LL Price, American farmer JA Shaw, American farmer Ray Tribble, American carpenter Ed Devaney, American farmer Travis Thomas, American farmer George Holland, American farmer Jim Pennington, American farmer Davis Newton, American farmer Howard Armstrong, and American carpenter Bishop Matthews are the members of the jury.(Photo by Bettmann Archive via Getty Images)

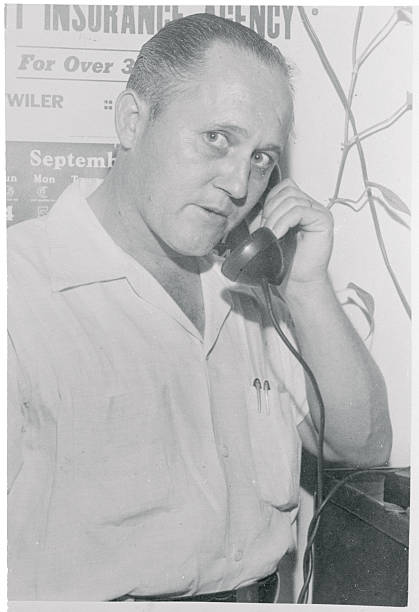

Raised Money for Till Murder Defendants. Sumner, Mississippi: Grocer A.B. Ainsworth, who started a fund to defend two white men accused of murdering a Negro boy, talks on the phone at Sumner, Miss. Ainsworth, of Greenwood, Miss., raised over $6,000 to defend half-brothers, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, who was acquitted here in the killing of the 14-year-old Emmett Till.

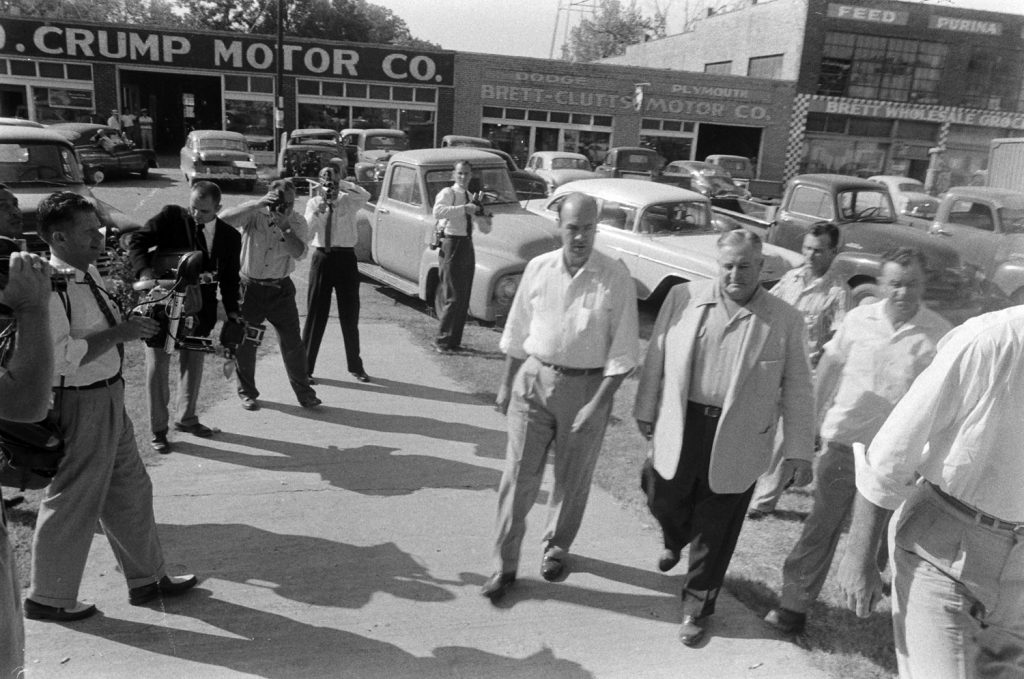

Defendant J.W. Milam arrived at his trial for the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till.

Ed Clark; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A scene outside the courthouse during the trial of Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam for the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till. Ed Clark; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A crowd gathered outside the Sumner, Miss., courthouse during the trial of Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam for the kidnapping and murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till. Ed Clark; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Part II: The Controversial Trial

The trial of J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant started on September 19th, 1955 at Tallahatchie County Courthouse. All the newspapers sent reporters to witness from the New York Times, the Chicago Defender to The Atlanta Consitution … However, the black reporters still had to sit in a separate area with white reporters and farther from the jury.

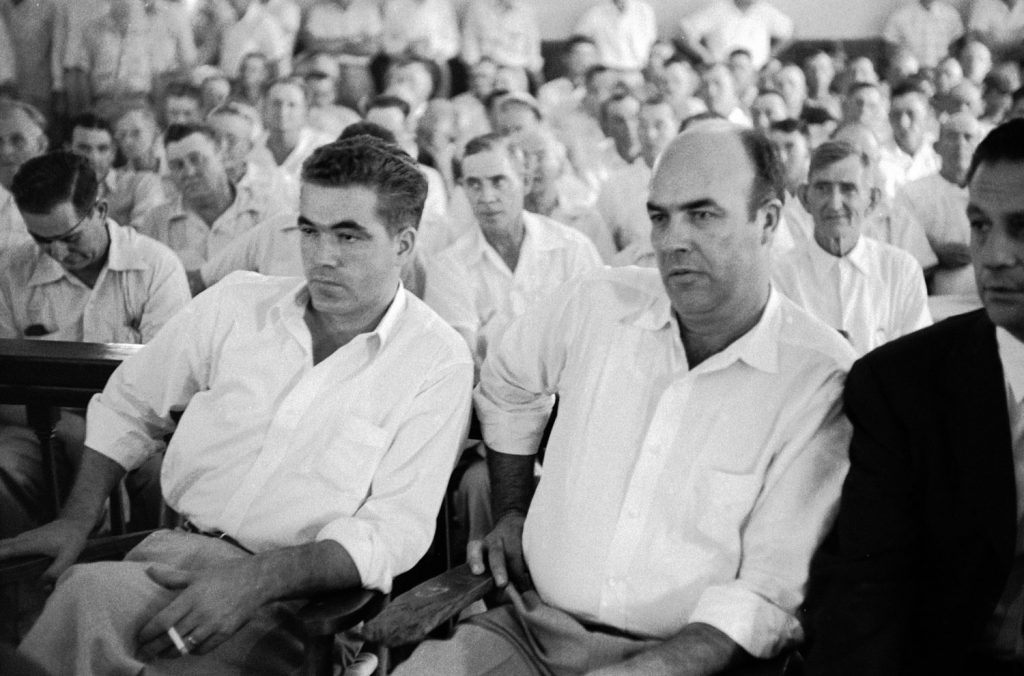

Defendants Roy Bryant, left, and J.W. Milam, right, during their trial for the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till.

Ed Clark; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

It was rare to have a trial like this in Mississippi. Every African American, who was brave enough to testify, was putting themselves in danger. Black people feared violent actions and segregation from the White people. However, the impact of an innocent 14 years old boy killed because of racism surpassed those fears. On the other hand, the entire jury had not a single colored person even though African Americans were 65% of the population in Tallahatchie County. All of the jury members were White.

Milam and Bryant went to the court with a lot of confidence along with their wives.

Mr. and Mrs. Roy Bryant (left) and Mr. and Mrs. J.W. Milan kissing after acquittal.

The chief police officer of Tallahatchie County, H.C. Strider was called to testify for the defendants. When being asked about the dead body, Strider claimed that it was impossible to identify the person even the color of his skin. And with just that claim, Mr. J.A. Shaw, the jury foreman, read the verdict: “Not guilty!”

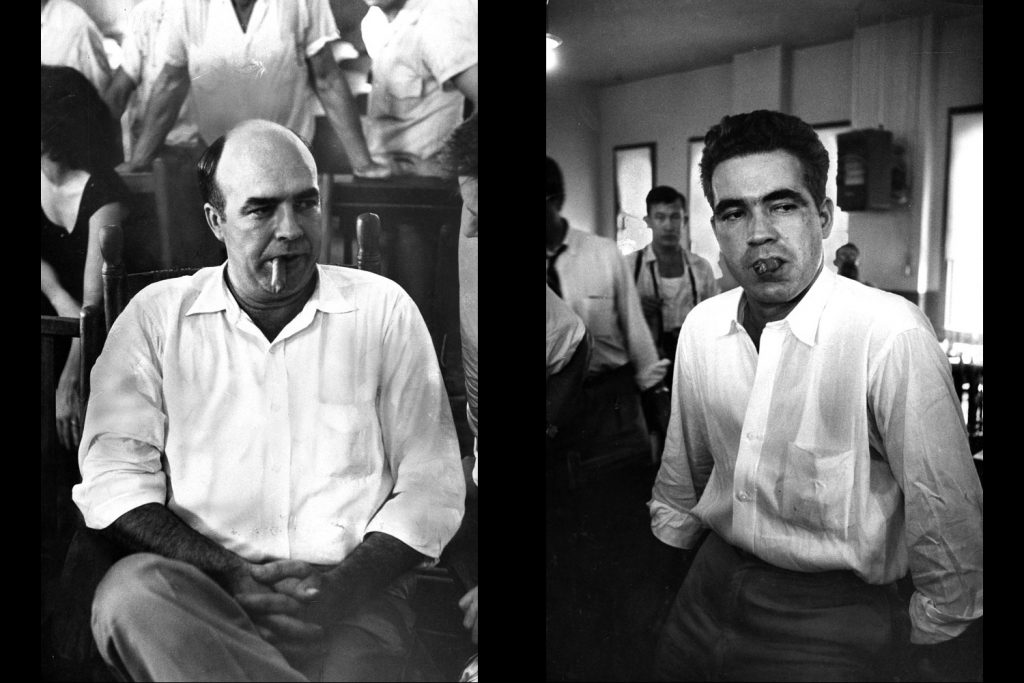

Roy Bryant (left), smokes a cigar as his wife happily embraces him. His half-brother, J.W. Milam, and his wife show jubilation. Bryant and Milam were cleared by an all-White, male jury of the charge of having murdered Till, a 14-year-old Chicago boy who was Black. The jury was out just one hour and 7 minutes.

More than ever, Americans seemed to be upset with the ridiculous result. During an interview with Chicago Defender after the trial, Mamie Till said: “This is the biggest joke I have ever witnessed.”

Even Mrs. Eleanor Rooservelt, the First Lady, had to speak up about the final verdict. She hoped that the United States of America needs to prove itself as an iconic figure of liberty, with justice must be served.

OCTOBER 11, 1955

NEW YORK.—In the current issue of Life Magazine, there is an editorial on the Till case which is an appeal to the conscience of all our people. The editorial says, quite rightly, that human justice often falls far short of being justice, but that divine justice sooner or later is meted out to all of us according to our just dues.

After reading this editorial I think the jury that allowed itself to be persuaded that no one had really found and identified the body—though it was granted that a boy had disappeared but the body found might not be his—and, therefore, the accused men could not be convicted or punished in any way, will find their consciences troubled.

It is true that there can still be a trial for kidnapping, and I hope there will be. I hope the effort will be made to get at the truth. I hope we are beginning to discard the old habit, as practiced in a part of our country, of making it very difficult to convict a white man of a crime against a colored man or woman.

I remember a train trip I made many years ago between Atlanta and Warm Springs, Georgia. I was with my husband. At one point we were delayed for a long time, and later we heard that a white man had shot a colored man on the train. Both of us were upset, and we asked if the white man had been arrested.

“Oh, no,” we were told, “but he might later come up for trial.”

Months later I was driving my husband through the county seat near Warm Springs when he pointed out to me a White man standing on the corner near the courthouse, and said with a wry smile, “There is the man who delayed us so long that day on the train. He is as free as he ever was, though the colored man is dead.”

I never forgot this incident, but now it has taken on added meaning. I know everywhere in this country we must prove that what we say about equality before the law for every American citizen is a reality and not a myth.

The colored peoples of the world, who far outnumber us, will watch the Till case with interest, and if justice in the United States is only for the white man and not for the colored, we will have again played into the hands of the Communists and strengthened their propaganda in Africa and Asia.

At the recent meeting in San Francisco Commemorating the signing of the United Nations Charter, a suggestion was made—I think by Israel—that a statue should be placed in San Francisco harbor to parallel in a way the Statue of Liberty, which everyone coming into New York harbor looks at with warm affection and gratitude. Now I have a letter from Arthur Robinson, of Volcano, California, saying that this statue should be a statue of justice and placed on Alcatraz Island, from which, he believes, the prison is shortly to be moved.

Mr. Robinson suggests that the money raised by groups like his own and those in San Francisco might well be supplemented by money coming from every United Nations member state, and he wants to get the project going because he feels that it should “catch fire in the hearts and minds of free men everywhere.” It might be a reminder to us as a nation that we stand as the symbol of democracy to the world, and that equal justice is looked upon as one of the essential parts of democracy.

If every citizen of our country were conscious of this, there might be no more juries such as sat at the first trial of the Till case.

E.R.

(Copyright, 1955, by United Feature Syndicate, Inc.)

Murderers Roy Bryant (left) happily leaves court with his half-brother, J.W. Milam

Although African Americans lost their support in Emmett Till’s murder in court, they finally showed the rest of the world why the Civil Rights Movement was necessary. Months later, protected by the double jeopardy rule, Bryant and Milam admitted to killing Emmett Till in an interview with Look Magazine in 1956. During the interview, Bryant and Milam even showed some disrespect towards Till’s death as to why people tried to keep the boy’s image live on.

Murderers J.W. Milam, left, and Roy Bryant, right, during their trial for the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till.

Ed Clark; Life Pictures/Shutterstock