Page 4 – 20

Louis Till

Emmett’s Father

Spouse

Born: February 7, 1922

Died: July 2, 1945 (aged 23)

(near) Fère-en-Tardenois, France

Louis Till

Louis Till was executed by the U.S Army in 1945 after being found guilty of murder and rape.

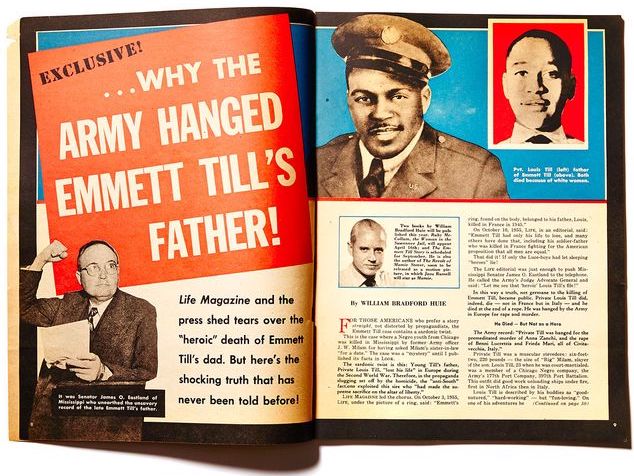

Mamie Till did not know about this incident until 10 years after the death of Emmett Till when more research was presented on Till’s family background.

Louis Till was serving overseas in the Transportation Corps of the U.S. Army during World War II.

The army was still segregated at the time, and he and another African-American private, Fred McMurray, were found guilty by an Army court-martial of raping two Italian women and murdering one during an air raid in 1944. Both men were hanged. Wideman isn’t convinced of their guilt.

“Louis Till nor Fred McMurray ever had a chance,” Wideman tells NPR’s, Scott Simon. “It was decided long before anybody even knew their names that some Black soldiers are going to take the fall for these crimes.”

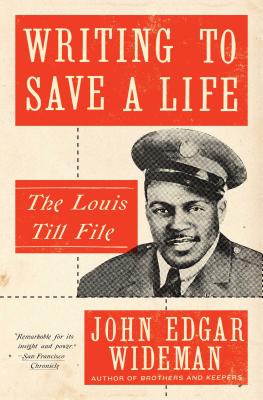

In “Writing to Save a Life” award-winning author John Edgar Wideman calls attention to Louis Till, Emmett’s father, a father the boy never knew. The book was 10 years in the making. A recent portrait of Wideman in The New York Times Magazine states: “It is the late-phase masterwork of a man still trying desperately to figure out how America works at a time when his perennial concerns — freedom and confinement, policing, fatherhood, the inheritance of trauma and ontological stigma — feel as pertinent as ever.”

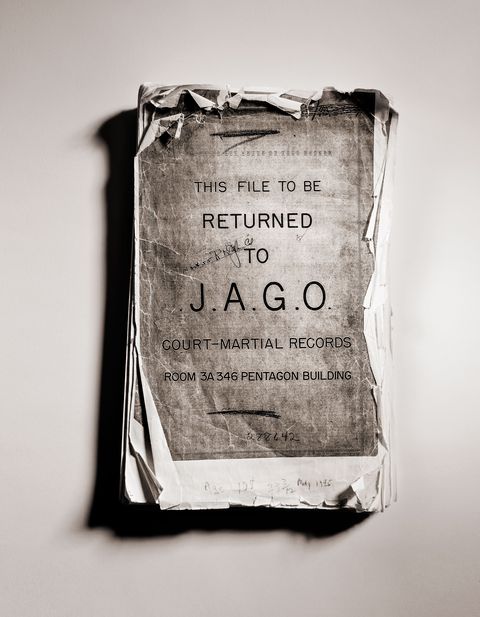

Mamie Till’s relationship with her husband Louis was not a happy one. He was abusive. With World War II in full swing, Louis stood before a judge and was given the choice of going to prison or joining the U.S. Army. He chose the latter and wound up a soldier in Italy. In June of 1944 in the Italian town of Civitavecchia he would be accused of “assault, rape, murder.” Wideman’s perusal of the convoluted military court transcript leads to the observation that young Louis Till’s trial was a sloppy and tendentious affair. Argues Wideman: “Colored soldiers whom the army considered second-class citizens were suspects who possessed no rights investigators need respect. The logic of Southern lynch law prevailed. All colored males are guilty of desiring to rape white women, so any colored soldier the agents hanged could not be innocent.”

Louis said nothing in his defense. He sat unyielding, silent. Wideman imagines Louis resigned to a racially charged enclosure tightening inexorably about him with no doubt about the outcome. He was hanged along with another Black soldier on July 2, 1945. Louis said nothing in his defense. He sat unyielding, silent. Wideman imagines Louis resigned to a racially charged enclosure tightening inexorably about him with no doubt about the outcome. He was hanged along with another black soldier on July 2, 1945. Says Wideman: “Till’s crime is a crime of being, I decided, after spending hours and hours one afternoon, poring through the file, an afternoon not unlike numerous others, asking myself how and why the law shifted gears in its treatment of colored soldiers during World War II. Asking why colored men continue to receive a summary or no justice, a grossly disproportionate share of life sentences and death sentences today.”

East of Paris is a cemetery containing 96 American soldiers who were executed for serious crimes. Markers have no names, only numbers. Louis Till is Number 73. Of the 96 buried men, 80 are black. Wideman writes: “War stories. Sea stories. Love stories. Till file full of stories. Of lies and truth. Shake them up. Dump them on the table. Then what. Why. Louis Till was not stuck like a bone in the county’s throat. America’s forgotten Louis Till, no sweat. It’s me. I’m the one who can’t forget. My wars. My loves. My fear of violent death. I’m afraid Louis Till might be inside me. Afraid that someone looking for Louis Till is coming to pry me apart.”

The Grave of Louis Till

“Louis Till was hanged at the stockade at Aversa, Italy on Monday, July 2, 1945. His body was transferred to the American Military Cemetery at Oise-Aisne in 1949, where he was buried in grave # 73 in the fourth row of the plot known as “the fifth field. The Army sent his personal effects home to his estranged wife.”

“Again and again in courtrooms across America, killers are released as if colored lives they have snatched away do not matter.”

*

Jerry Smith Sr.’s personal story is one of unwavering patriotism and selflessness. Despite facing prejudicial treatment from the US military after being injured in combat, he continued to serve his country as a Police Officer with utmost dedication and loyalty. His commitment to defending our nation’s values and freedoms is truly commendable.

The Purple Heart Medal is awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces who have been wounded or killed in action against an enemy of the United States or as a result of an act of any such enemy. It serves as a symbol of honor, sacrifice, and valor – qualities that Jerry Smith Sr. exemplified throughout his military career.

It is deeply disheartening that despite sustaining injuries directly related to combat operations during the Vietnam War, Jerry Smith Sr.’s ethnicity became a barrier preventing him from receiving this well-deserved recognition.

In Honor of A Purple Heart

@ ALL RIGHTS RESERVED – Iforcolor.org/Dale Shields

NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED